image by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

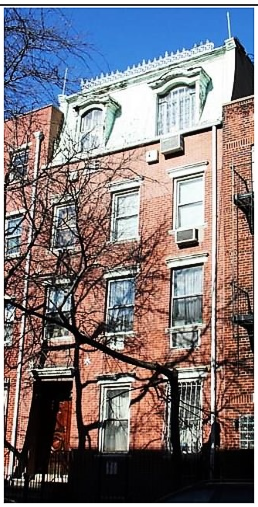

No. 271 East 7th Street was one of a row of fine, brick-faced homes completed in 1843. Like its identical neighbors, it was 22-feet-wide and three stories tall. The full-height third floor, normally much shorter in Greek Revival houses, showed the influence of the emerging Italianate style. The upscale tenor of the residence was reflected in costly extras, like the marble stoop.

Although situated in what was known as the Dry Dock District, just about a block from the East River shipbuilding area, the residents of 271 East 7th Street were not involved in that industry. The rapid turnover of occupants suggests the house was initially rented. Grocer Joseph Cobb and his family lived here from 1851 to 1852, followed by William Wells, a butcher, and his widowed mother Eliza in 1853 and '54.

In 1856 Edwin L. Tallmadge and his family moved in. Listed as a carman, he was most likely the owner of a delivery firm, rather than merely being a driver. He and his wife, Ann E. Tallmadge, had five children, Edwin Jr., Herbert H., Harry E. Willard P. and Ella A. The family also took in a boarder, Elizabeth Elting, who taught in the Girls' Department of Public School No. 15 on Fifth Street. The family would remain in the house until 1861, when Tallmadge sold it to a neighbor, John A. Squires.

The Squires family had lived half a block away at 298 Seventh Street (the East would be added decades later). John and his wife, the former Mary R. Nevins, had two sons, John H. and Joseph H. A third, Robert A. Squires would be born in 1864.

At some point Squires updated the Greek Revival house with Second Empire elements--a slate-shingled mansard with two dormers and lacy iron cresting, and arch-paneled doors within a modernized entrance now bereft of the Greek Revival framing.

The family had barely settled in before trouble arose. Among their domestic staff was Julia Madden. On February 25, 1861, she bundled up "wearing apparel, furs, jewelry and money to the amount of $75," according to the New York Express, "and decamped with the plunder." When police went to her home at 15 Baxter Street, they found the stolen goods. On March 12, the New-York Daily Tribune reported, ""Julia Madden, a young girl of 17, in the employ as servant-maid of Mary R. Squires...pleaded guilty." She was sent to the State Penitentiary for two years.

John A. Squires was a partner in the painting firm of Hogg & Squires. The partnership was dissolved on September 11, 1865, with a notice in the New York Herald announcing "The business will be continued by John A. Squires."

Just over a week after taking over the establishment, John and his wife experienced heartbreak. On September 21 their nine year old son, Joseph, died. His funeral was held in the parlor three days later.

Following John H. Squire's marriage to Hannah Tyrie, the newlyweds moved into the East 7th Street house. Interestingly, the bride brought along her two brothers, John and James, as well. Her father-in-law took at least one of them, James, into the painting business.

The joy of a marriage soon dissolved into a string of tragedies. On October 5, 1868 John J. Tyrie died at the age of 29. His funeral was held in the house two days later. A year and a half later, on May 4, 1870, John H. Squires died at the age of 22.

At the time of his brother's death, Robert A. Squires had just turned eight years old. His father had changed his profession to the veneer business. Robert was visiting his father's shop at 205 Lewis Street on July 13, 1871 when the unthinkable happened. The New York Herald reported that he "was run over by one of the cars of the Belt Line Railroad at the corner of Lewis and Eighth streets and killed." The funeral of the last of the Squires' sons was held in the house on July 16.

At some point Hannah Squires's sister, Cecelia, and her husband William A. Collyer moved into the East 7th Street house. The string of sorrowful ceremonies continued when Cecelia's funeral was held on May 20, 1874. She was 30 years old. Only seven months later, another funeral was held in the parlor continued. Mary R. Squires died on December 15, 1874 at the age of 48.

John A. Squires sold his veneer factory two months later and presumably retired. All three occupants of the East 7th Street house--John Squires, Hannah Squires, and William A. Collyer--were now all widowed. John took in two boarders that year, Moses Sulzberger, a drygoods merchant, and his widowed mother, Babbette. Almost unbelievably, Babbette died in her room on September 2, 1875 at the age of 69. Yet again, a funeral was held in the parlor.

Moses Sulzberger remained with the family through 1880. In 1881 John A. Squires moved to Piermont, New York and transferred title of 271 East 7th Street to William A. Collyer "during life of John A. Squires." In 1886 he leased it to attorney Joseph Emanuel Newburger.

Born in 1853, Newburger was a bachelor. Moving in with him was his unmarried sister, Hannah (who ironically taught in the Boys' Department of Grammar School No. 15 where Elizabeth Elting had worked decades earlier), and his widowed mother, Lottie. Aside from his legal practice, he was highly active in Jewish affairs. He was a founder of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, president of the Independent Order of B'nai B'rith District No. 1 and president of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum among other activities.

Newburger was elected a City Court judge in 1890, and would become a Justice of the New York State Supreme Court in 1905. His occupancy would start a tradition of judges in the East 7th Street house.

Joseph E. Newburger on commencement day at Columbia University in 1914. from the collection of the Library of Congress (cropped)

John A. Squires died in April 1891 and the following year his estate sold the house to Charles Seligman for $16,000 (about $469,000 today).

The Seligmans would remain in the house only until March 1901 when it was purchased by Justice Benjamin Hoffman "for his own occupancy," according to The Sun. The judge and his wife, Rebecca, had four children, Belle, Eva, Ruth and Joseph Benjamin. Before moving in, Hoffman hired the architectural firm of Rogers & Stander to do interior renovations, including "new windows, partitions and floors," according to their plans. The updating cost Hoffman the equivalent of $37,700 in 2022 dollars.

The Hoffman girls were the center of social attention within the family. On December 11, 1904, for instance, the New York Herald reported, "Mrs. Benjamin Hoffman will give a debutante tea for her daughter, Miss Belle Hoffman, at her residence, No. 271 Seventh street, to-day."

As they grew to be young women, debutante entertainments turned to weddings. Eva's engagement to Nathan Ries was announced in November 1912, and Ruth's to Newton M. Shack came in September 1917.

By the time of Ruth's engagement, the Hoffmans had shared 271 East 7th Street with the David Lazarus and his wife, the former Molly Lemlein, for at least seven years. The couple had two grown children, Bella and Lester. Lazarus and Hoffman had a close professional connection. While Judge Hoffman was the Sixth Assembly District leader of Tammany Hall (appointed in 1891), Lazarus served as his deputy. In December 1910 Lazarus was elected to take Hoffman's seat.

A massive meeting was held in the Hoffman home in September 1918. The Evening Telegram reported on a bronze tablet to be placed in Hamilton Fish Park honoring the East Side "soldier boys who have fallen on French battlefields." The article noted, "This was decided at a representative meeting of 100 residents of the east side, including the mothers of the heroes, held at the home of Judge Benjamin Hoffman."

When women obtained the right to vote in 1920, Rebecca Hoffman stepped up. She was appointed co-leader of the Sixth Assembly District with her husband, who had regained the seat. Always active in politics, she had helped found the Progress Relief Society in 1895, and still served as an officer.

Benjamin Hoffman suffered a fatal stroke on May 20, 1922 at the age of 58. The New York Herald mentioned, "Recently he had been working on rent cases and had disregarded the warnings of his physician that he lessen his labors on the bench." His funeral was held in the house on May 22. Among the several judges to serve as pallbearers was David Lazarus.

Hoffman's death left the position as Tammany leader of the Sixth Assembly District unfilled. Lester Lazarus, who was still living with his parents in the East 7th Street house, was a Deputy Assistant District Attorney. He was appointed to replace Benjamin Hoffman as Assembly leader on July 28, 1922. The New York Herald mentioned, "The salary is $9,000 a year. He formerly received $4,000 a year as Deputy Assistant District Attorney." His new salary would equal about $139,000 today.

Rebecca Hoffman was still the district's co-leader, and following her husband's death, she became even more active in politics. That year she served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, and would do so again in 1924 and 1928. When she ran for reelection as Register of New York County in 1928, Mayor James Walker deemed her, "the queen of the ticket." The Elmira Star-Gazette said, "When she came to office, at a salary of $12,000 a year, she was the highest paid woman public official in the state, and one of the highest in the country."

She held that position until her death on June 16, 1931. In reporting her death, The New York Sun commented, "For thirty-five years she had made her home at 271 Seventh street, known as Political Row."

The entire Lazarus family continued on at 271 East 7th Street and at their summer home in Rockaway Park. On August 7, 1933 The New York Sun reported on David's 75th birthday, noting that he spent "fifty of them in the Tammany organization." He was now a Commissioner of Records in the Surrogate's Court.

It is unclear when the Lazaruses left the East 7th Street house. It was seemingly being operated as a rooming house by 1937. Although it has never been officially converted to a multi-family building, today it holds five apartments.

photographs by the author

many thanks to reader Joe Ciolino for prompting this post

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment