Around 1850 two modest, mirror image houses were completed on East 26th Street, just east of Third Avenue. The working class, immigrant neighborhood was known as the Gas House District because of the sprawling Metropolitan Gas Light Company's gasworks between East 22nd and 23rd Street, from First Avenue to Avenue A. Residents also shared the neighborhood with lumber yards and a stone-and-lime yard, as well as the notorious Gas House Gang.

Despite their gritty surroundings, the houses boasted handsome Italianate detailing. The elliptically arched openings wore molded brownstone lintels. Paneled fascia boards enhanced the cornices, upheld by foliate brackets. Both houses had a store in the basement level.

Frederick H. Ahrens, an "ink man," operated his business at 113 West 26th Street (renumbered 203 in 1867) by 1853. He lived at 330 Third Avenue where he also ran a grocery store. By 1857 both this store and the one next door at 115 were home to Francis Ripperger's shoe store (one, perhaps, for men's shoes and the other for women's and children's). Interestingly, he lived at 330 Third Avenue, the same tenement in which Frederick H. Ahrens lived.

Living above the store at 113 in 1857 was Jacob V. Hutschler, who ran a saloon at 339 Third Avenue. He would remain here at least through 1863. His next door neighbor at 115 was in the same business. George Tator's saloon was on East 24th Street.

Despite what must have been tight conditions, Tator took in two boarders. In 1865 two school teachers lived here. Alexander Morehouse taught in the boy's department of School No. 20 on Chrystie Street, and Augusta S. Van Noy taught at School No. 19 on 14th Street.

The same was true next door by the mid-1870's. An advertisement in March 1876 offered a "nicely furnished parlor and bedroom" for $6 per week, or a "second story front room" for $4, "meals if desired." The rent for the more expensive accommodations would equal about $165 per week in today's money.

The store space in 203 East 26th Street was home to Herman Kahn's grocery store by the early 1880's. On July 22, 1882 Mary Moakley came in and asked for a quart of peas and three lemons. The New York Dispatch said, "She was so far pregnant that she could scarcely walk." Mary Moakley's bill was 15 cents. Kahn gave her the items, and briefly walked outside. When he returned she demanded, "I gave you a dollar bill. I want my change."

The New York Dispatch reported, "No bill was given him or his clerk. He sent out for a policeman, took the basket from her, and she waited till the policeman came." The article added, "The officer was long in coming, and she could have escaped, but for her condition."

Both Moakley and Kahn told their stories to a magistrate. The New York Dispatch wrote, "She was not believed in the Police Court, nor in the Sessions." For attempting to steal 15 cents worth of peas and lemons, and 85 cents in change, she was sentenced to 10 days in City Prison.

In the meantime, Michael Sweeney had lived in 205 East 26th Street since the early 1870's. His store at 352 Third Avenue was listed as "butter" in 1873, but by 1879 he had branched out to include teas. He sold the house to the James Hall family in the mid-1880's, around the time he changed his business once again, to a liquor store.

Living with James Hall and his wife, the former Frances Sweeney, were nephews Michael, Thomas, George, Matthew and John Brannelly. The boys were the sons of Frances's sister, Bridget Sweeney Brannelly, and Patrick Bernard Brannelly.

Another Irish immigrant, Patrick Curley, rented a room in 1889. When a friend, James Giblin, applied for a Civil Service job that year, Thomas Brannelly and Patrick Curley testified to his good character.

James Hall died on February 20, 1888, and John F. Brannelly died on October 10, 1894 at the age of 22. Both funerals were held in the East 26th Street house.

Living next door the year of John Brannelly's funeral was Ellen Burke, who also came from Galway, Ireland. The unmarried woman was looking for work in 1895, advertising, "Chambermaid and seamstress--or assist with growing children; best city references. Miss Burke, 203 East 26th st."

A year before placing that ad, Ellen had been disturbed by a window display across the street. On May 2, 1894 The Press reported, "At No. 202 East Twenty-sixth street, near Bellevue Hospital, is the surgical instrument shop of Eyers & Co., who have a large consignment of male and female skeletons and skulls on exhibition. The skeletons are in various stages of articulation, and two of them are in the shop windows. One of them is by no means a cheerful looking object, as the cartilage has been left sticking to the ribs."

Ellen Burke got together with her neighbors to write a protest letter to the Board of Health. Among those who signed the petition was Michael Sweeney, who had lived next door, and 500 girls employed in a nearby factory. The article said the workers wanted the skeletons removed so "they will not spoil the girls' midday lunch or give them a nightmare." John Drake, of Eyers & Co., called the protestors "silly" and said "a nice, fresh skeleton is no more objectionable than a coffin or red flannel underwear in other shop windows."

Never married, Ellen Burke died at 203 East 26th Street on July 23, 1903. Her funeral was held in the house two days later.

Living with the Brannelly's that year was blacksmith William P. Black. He "caused some excitement in Madison Square Park last night," said The Sun on November 16, 1903. The article explained, "Black, who was drunk, made a remark to a woman which she resented." Upon being reprimanded by the woman, Black "pulled a big revolver from his pocket and began to dance around, waving it over his head." People in the park fled in panic. They drew the attention of Policeman O'Connor, who rushed to the park. When Black saw the officer's drawn firearm, he put his away. The Sun said, "O'Connor had no trouble in locking him up."

George E. Brannelly's funeral was held in the parlor on January 11, 1907. The 30-year-old had died two days earlier. Following his funeral, a solemn requiem mass was held at St. Stephen's Church on East 28th Street.

In 1911 a grocery store occupied the lower level of 203 East 26th Street and by 1917 the house was described as a tenement, a term applied to almost any multi-family dwelling. It was the scene of a disturbing incident on the morning of January 10, 1917. The New York Herald reported that school children passing by, "saw a young woman topple and fall headlong in the hallway."

Two young girls rushed to her aid, and when they realized she was unconscious, sent a boy to get help. Policeman Rider recognized the stains on her lips and fingers as iodine. Josephine De Leon did not live in the house, but on First Avenue. She had simply ducked into the open door of 203 East 26th Street to swallow the poison. The 18-year-old was revived at Bellevue Hospital, where she said this was her third attempt to die. "She explained that her life was a history of trouble, and that she would be better dead," reported the New York Herald. The article noted that the quick actions of the school children had saved her life.

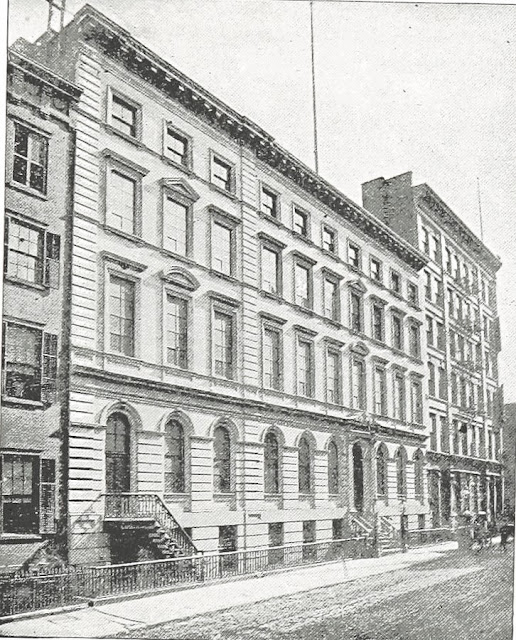

In 1983 both houses retained their parlor floor windows. via the NYC Dept of Records & Information Services.

Beginning around 1925 the store at 203 East 26th Street was home to the King Cole Sound Service. An advertisement that year offered "standard, portable, motion picture equipment, operators for entertainment in churches, home, &c." The store remained in the space at least through 1947.

Both houses were renovated in 1986, resulting in store space in the cellar and first floors, and one apartment each above. While the little houses with their varied histories have been sorely abused, they manage to retain their charm.

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.jpg)

.jpg)