The Abingdon Square Hotel opened in 1892. It engulfed the Bleecker Street blockfront from Abingdon Square to Bank Street. (The block-long portions of Eighth Avenue and Hudson Street on either side of Abingdon Square were named for the park.) The eight-story hotel offered rooms at "$2 and up."

In 1929 real estate operators Bing & Bing purchased the old hotel and several abutting houses as the site of a modern apartment building. But, perhaps because of the onslaught of the Great Depression, after the structures were demolished, the project stalled.

The corner sat vacant for nearly a decade when, in December 1938, A. A. Silberberg purchased the property from the Guaranty Trust Company. His architect, Irving Margon, filed plans for a six-story, $200,000 apartment house. Called the Abingdon Court, its construction was completed the following year in September.

Margon's Art Moderne design was executed entirely in brick. Bold orange brick courses, belted with dark brown brick, stood out against the beige facade. Streamlined fire escapes that closely matched the rooftop railings were designed as part of the architecture. To make them less obtrusive and to provide dimension, on the Bleecker Street side Margon set the fire escapes within a recess, and dramatized the chamfered corners with faceted windows.

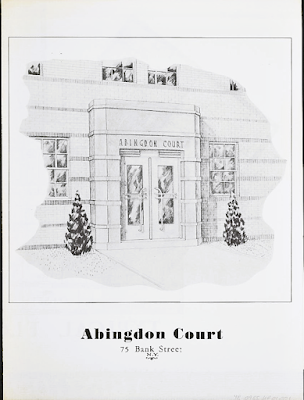

The entrance, on Bank Street, sat within a deep "garden court." Above the door within a banded, black-veined stone frame was etched the name Abingdon Court.

The entrance was featured on the cover of an 1939 brochure. from the collection of the Columbia University Library.

The building offered 87 apartments of from two to four rooms. Despite the Depression, on November 14, 1939, A. A. Silberberg told a reporter from The New York Sun, "It is not only completely occupied, it has a waiting list." He added, "Incidentally, I think you will find the trees outside the building very attractive. And our garden too."

A brochure published that year listed amenities like sunken living rooms, separate dressing rooms, Westinghouse refrigerators, "chromium fixtures," and "room size foyers." Atop the building was a roof garden for residents.

Rents for a two-room apartment started at $50, and for three-room apartments at $70--about $975 per month for the least expensive by 2022 terms.

In 1941 Natalie Bacal moved into Abingdon Court with her 17-year-old daughter, Betty Joan Perske. Following her divorce from William Perske in 1929, Natalie had legally changed her surname to Bacal, a version of her birth name, Weinstein-Bacal. Their move from Brooklyn may have been to make Betty Joan's studies at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts more convenient.

While studying at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, she began dating a fellow student, Kirk Douglas. She helped with household finances by working as an usher in the St. James Theatre, and as a model in department stores. A year after moving into the building, she was crowned Miss Greenwich Village and the same year landed a walk-on part in the Broadway show Johnny 2 x 4, which opened at the Longacre Theatre on March 16.

Betty Joan's face appeared on the March 1943 cover of Harper's Bazaar. It caught the attention of the wife of director Howard Hawks, who urged him to screen test the young model for his upcoming film To Have and Have Not. Betty Joan boarded a train to California on April 3, 1943. She not only got the part, but a seven-year contract with a weekly salary of $100 (about $1,570 today). Hawks changed her first name to Lauren, and Betty Joan chose a variation of her mother's name, Bacall, as her stage surname.

Lauren wrote to her mother about the filming, telling her that her co-star, Humphrey Bogart "is very, very fond of me." Natalie visited her daughter in California and was incensed to discover that the fondness had evolved into a relationship. Bogart was not only married, but was 25 years older than Lauren.

The 19-year-old Lauren Bacall in a scene from To Have and Have Not. from the Sight and Sound Magazine archives.

Soon afterward, Natalie Bacal moved out of Abington Court and rented a small furnished apartment in Beverly Hills for herself and Lauren. Her ongoing protests (and those of Howard Hawks) over the romantic affair were to no avail. On May 21, 1945 the now-divorced Bogart and Bacall were married.

In the meantime, the Abingdon Court filled with financially-comfortable, albeit significantly less glamorous, families. Among the Bacal's neighbors was the spinster former school teacher Ellen A. Leo. A graduate of Hunter College, she had worked as a teacher in the public schools until her retirement at the age of 68 in 1936.

Nathan and Shirley Spitzer moved into Abingdon Court in the mid-1930's. Nat, as he was known, had an easy commute to work. He operated the St. Vincent's Chemists pharmacy at 2 Bank Street, at the corner of Greenwich Avenue. Their son, Dr. Richard Alan Spitzer, who was born here in 1945, recalls, "The pharmacy was something of a neighborhood institution and my Dad highly regarded by the locals. Not infrequently he had customers who had appeared at the [Village] Vanguard, and once in a while Joe Gould would make an appearance." Nathan Spitzer sold the pharmacy and the family moved to Queens around 1951.

The United State's entry into World War II caused changes in the lives of Americans, including residents of Abingdon Court. Textile manufacturer Harry Rosenfeld was stopped by a Port Authority policeman on February 23, 1942 and was unable to provide his draft card. The 41-year-old "said he had registered, but had left his card at home," reported The New York Sun. Unfortunately for Rosenfeld, forgetting his card was not an acceptable excuse. The article explained, "The law provides a maximum penalty of five years in jail and $10,000 fine for men of draft age who do not carry their cards." Rosenfeld was jailed in lieu of $1,000 bail.

War restrictions affected American's vacation plans, as well. Gas rationing meant that in order to use one's vehicle for leisure travel required a Government-issued "vacation permit." The first to apply in the summer of 1943 was Abingdon Square resident Julius Lowenthal. The Sun explained the certificates "will permit [holders] to use their A gasoline ration coupons to drive their cars on vacation trips." Lowenthal's application was approved, allowing him "to use his car to get to Lake Kauneonga, N.Y, where he will stay from July 17 to August 1," said the article.

On March 24, 1946 resident C. R. Lehigh encountered a terrifying intruder in the building. Having recently returned from four years of service in the Pacific during World War II, Lehigh was now the automobile and yachting editor of the Newark News. Early that morning he returned to Abingdon Court. The New York Sun reported, "As Lehigh entered a self-operated elevator he faced a man with a drawn revolver. The thief ordered him to hand over his valuables, and Lehigh, looking into the muzzle of the unwavering gun, produced $41." After the robber fled, a no-doubt shaken Lehigh called police.

When America entered the war, lawyer Harry H. Rifkin was appointed an official in the Office of Price Administration. He first served as enforcement attorney, and then as director for the price agency for meat and poultry. He returned to his private law practice following the war. He lived in Abingdon Court with his wife, Shirley, where he wrote several short stories for various magazines about life during the Depression years in the 1960's.

Living in the building by 1970 was photographer Leo Stashin and his anatomist wife, Dr. Judith Hardy Stashin. Leo's passion was the collecting of 19th century photographs and daguerreotypes. The New York Times said his collection included "American statesmen, actors, inventors and businessmen." In rummaging through a Greenwich Village art shop, he came across an 1849 daguerreotype "which he identified as one of Abraham Lincoln," said The New York Times. (Experts tended to disagree.) Confirmed images in his collection were of Presidents John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore and Franklin Pierce. Stashin was working on a book about the Abraham Lincoln daguerreotype in 1973, when he died of cancer at the age of 54.

Irving Margon's confident Art Moderne building, sitting conspicuously at an intersection of three parks, is nearly unchanged in its more than eight decades.

photograph by the author

many thanks to reader Dr. Richard A. Spitzer for requesting this post

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

Residents also included Jack and Madeline Gilford and Zero and Kate Mostel, all victims of the horrible blacklist in the 1950's.

ReplyDeleteI found a photo from 1932 depicting the new Bing & Bings and the demolished Abingdon hotel at www.oldnyc.org -- the caption reads: "1932; 1938 (1) Abingdon Square, looking north from Hudson Street at Bank Street, where Eighth Avenue branches off to the right. New apartment buildings, 299 West 12th Street on north side of square, and building at S.E. corner of Eighth Avenue and 12th Street. Behind bandstand is vacant lot where Abingdon Hotel has been demolished. March 15, 1932. P. L. Sperr, Photographer. (2) The same view as No. 1 but four months later, showing in background the skeleton of Port Authority Building between Eighth and Ninth Avenues just north of 14th Street. July 17, 1932. P. L. Sperr, Photographer. Neg #2282 (From www.oldnyc.org/#715881f-b"

ReplyDelete