from the collection of the New York Public Library

In 1854 the infamous Tammany Hall politician Fernando Wood was elected mayor. He immediately initiated a system of open corruption in appointing and promoting officers within the Municipal Police Department. The state, however, did not stand idly by. On April 15, 1857 the Metropolitan Police Act was signed into law by Governor John King. This effectively disbanded the old Municipal Police Department and took policing out of the hands of Wood. Corrupt cops were dismissed and while others, were reinstated.

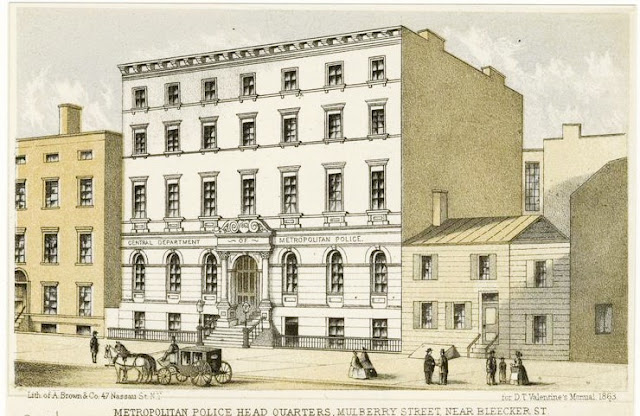

While the Metropolitan Police Department initially took over the old headquarters at 413 Broome Street, plans were almost immediately laid to erect a new structure. In 1862 property was acquired on the east side of Mulberry Street between Bleecker and Houston Streets. Construction on the new building was completed in January the following year.

Four stories tall above a high basement level, the headquarters was faced in gleaming white marble. Gas lamps with green glass panels atop the stoop newels identified the building, especially at night. The Italianate design featured a rusticated base with arched openings and an impressive entrance flanked by engaged Corinthian columns that upheld an entablature. It was crowned by a swan's neck pediment with a shield carved with the date of construction. Each of the upper floors was delineated by a stone bandcourse, and the windows on prominent molded sills were fully enframed.

The department moved into the new building at 300 Mulberry Street in two stages--the Board of Police Commissioners settling in first during the second week of February. On February 25, The New York Times reported, "Yesterday the entire department was removed, consisting of the office of the detective police, the telegraph office, also that of the Superintendent, the Inspectors of Police and the rendezvous for lost children."

The article was quick to point out that construction costs had been covered by the Contingent Police Fund, and "thus the New-York public will not be directly taxed for the expense of the erection and fitting up of this fine four-story marble front building." The writer noted, "The entire building is arranged with especial deference to the wants and conveniences of those connected with the Police Headquarters, and reflect much credit upon the architect."

The opening of the headquarters took place during the height of the Civil War. Less than four months later, on July 11, 1863 the nation’s first attempt at a military draft played out in New York with a lottery. When the first 1,200 chosen names were published, it was obvious that they were overwhelmingly from the city’s poor and immigrant population—the wealthy had either bought exemptions or used their political power to circumvent the draft. The result was the Draft Riots—a three-day reign of terror and carnage unlike anything seen in the country before. As worded by Police Commissioner John G. Bergan, "riot, robbery, arson and murder, raged over the City."

The police department battled the mobs alongside the National Guard. In one case, Colonel Mott's men "had a contest with the mob in the vicinity of Gramercy Park," according to Police Commissioner John G. Bergan in a letter on July 28. A sergeant was killed and the guardsmen, forced to retreat, "left the body among the enemy." An "expedition" from Police Headquarters was assembled to recover the sergeant's body.

The city faced what could have been an equally disastrous incident the following year. A group of Confederate conspirators devised a plan to burn New York City. Members checked into hotel rooms across the city and committed synchronized arson, theorizing that the Fire Department, receiving multiple alarms from across the city, would be unable to attack all the blazes and the fires would spread ferociously.

Each terrorist piled the furniture and bedding in the center of his room, doused it with turpentine, and, having set it aflame, sauntered out of the building. The first alarm sounded came at 8:43 on the evening of November 25 from the St. James Hotel. Within minutes Confederate Army Captain Robert Cobb Kennedy had set Barnum’s Museum on fire. Quickly fires were discovered in the St. Nicholas, the United States Hotel, the Metropolitan, Lovejoy’s and the New England Hotel.

Lumber yards were also torched. And the Confederates' plan would have worked had it not been for the quick action of hotel employees. Unbelievably, by dawn the fires had been extinguished.

Now the police department was tasked with finding the perpetrators. And only three months later the last of the four, Robert Cobb Kennedy, was in custody at 300 Mulberry Street. The New York Dispatch said of him, "A more out-and-out rebel never lived." The article said "to look upon his face as it rests in quiet," one could not imagine that he was "connected with the nefarious attempt to burn our hotels and places of amusement, and scatter desolation and death over our fair metropolis."

The Metropolitan Police Headquarters was also the "rendezvous for lost children." On July 8, 1865 the New York Herald reported that during the previous year 3,477 children were brought here. The article noted, "3,266 were there claimed, and the remaining 211 were sent to the Commissioners of Charities and Correction, there appearing no claimants for them."

Also housed in the building were the District Court Squads, which oversaw the various court district courts, the Sanitary Corps, and the Detective Department. In the basement of the building was the nerve center for the police telegraph system. On January 8, 1871 the New York Dispatch explained, "A network of telegraph wires encircles the city, all terminating at No. 300 Mulberry street." There were between 75 and 80 miles of police telegraph lines in the city. Transmissions could be sent to or received from each of the precinct stations, and Bellevue Hospital. "This office is never closed, day or night, and is invaluable to the public in the recovery of lost property, strayed children, accidents, fires, and casualties," said the article.

The corruption that had prompted the state to abolish the Municipal Police Department had never truly disappeared within the Metropolitan Police Department. On August 9, 1901 The Evening World recalled, "The seeds of corruption, the seeds of decay, were in it from the beginning...But at least life and property were safe under 'the finest.' And the strong, if corrupt, hands of the leaders of the force restrained the elements which they corruptly tolerated."

However, by 1895 the malfeasance was once again out of control. Change would begin on May 6 that year with the installation of a new reform-minded Board of Police Commissioners, headed by 36-year-old Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt and his commissioners initiated numerous reforms within the department.

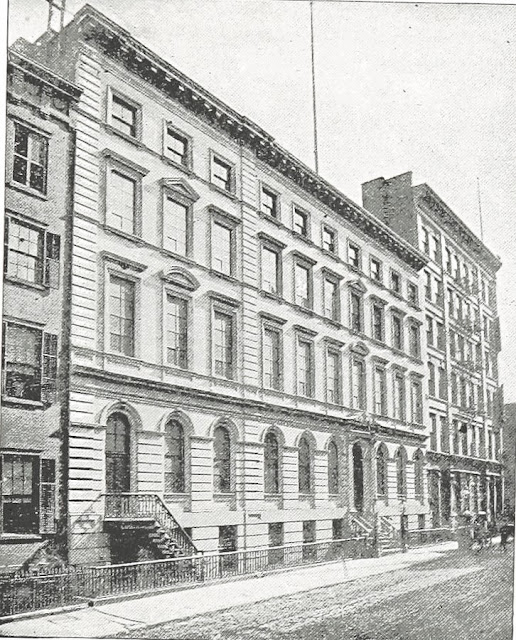

Before 1893 a nearly seamless addition had been added to the north. Kings Views of New York City, 1893 (copyright expired)

Although the building had been expanded in the late 19th century, in 1901 Police Commissioner Michael C. Murphy pushed for a new headquarters, saying 300 Mulberry Street was "too old and too small and too far downtown." By the following year, when the department had a new commissioner in John N. Partridge, the plan had gained momentum. On September 12, 1902 Partridge announced he had selected a site for a new headquarters. The Evening World reported he "suggests that the old Headquarters property be sold and that the amount realized be applied on the new building and property."

As the magnificent new headquarters building at 24 Centre Street was nearing completion in January 1908, Frank Marshall White titled his article in Harper's Weekly "The Passing of '300 Mulberry Street.'" Comparing it to Scotland Yard for figuring "in history and fiction," he recalled the Draft Riots, the Orange Riots of 1871, and the famous officers--good and bad--who had worked within the building. "It was at 300 Mulberry Street that Thomas Byrnes, at the head of the Detective Bureau, made an international reputation as thief-taker, and here that he originated the mysterious 'third degree' that has been the undoing of many a criminal since." Other terms originated at 300 Mulberry Street, White recounted, were "gold brick," (and the "original gold brick is today among other relics of crime" at the building, he said), and "copper," meaning an officer. At 300 Mulberry Street was displayed a collection of early copper badges.

At midnight on November 27, 1909, Police Commissioner William F. Baker "pressed a key which switched all the telegraph and telephone lines" from 300 Mulberry Street to 240 Centre Street. In reporting on the move, The New York Times remarked, "No other building in the city, probably, is richer in memories than 300 Mulberry Street. It is famous all the world over." The journalist recalled some of the renowned crimes solved there and the "noted criminals, murderers included, whose names are intimately associated with the hold structure." Among the colorful names were "Red" Leary, "Humpty" Williams, and Liverpool Jack.

The venerable building was not totally abandoned, however. The office of the Chief City Magistrate, the Traffic Court, the Probation Bureau, the Fingerprinting Department and the "old record room" continued to be housed here.

The Traffic Court had its most celebrated prisoner on June 7, 1921--baseball great Babe Ruth. When word got out that he was being held in the detention room, "there was a rush for the 'jail' by court attendants, pretty girl stenographers and other baseball hero worshippers," reported The Evening World. That portion of the building had to be shut off. Things got tense as the clock ticked away and the slugger's case had not been heard and the 3:30 game time moved ever closer.

Ruth's uniform was delivered to 300 Mulberry Street and at 3:00 his two-seated roadster was sitting at the curb, running. Finally, after being fined $100 for speeding, Ruth was set free at 3:45--15 minutes after the game began. To ensure he made it to Yankee Stadium Magistrate McGeeghan rode along, presumably "to see that if he speeded he would do it within the law."

A memorable modernization occurred later that year on September 15, 1921. The old gas lamps were removed, replaced by electric lamps. The New York Herald noted that they had burned unceasingly for 59 years.

On January 6, 1922 a bronze tablet, designed by James E. Fraser, was unveiled in the third-floor office once used by Theodore Roosevelt. The mayor, city officials, and prominent New Yorkers were in attendance, and the Police Glee Club provided music. (The room would be officially dedicated as the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Room three years later, on March 14.)

Another department was added within 300 Mulberry Street in 1922 with the formation of the new Homicide Court. On October 3, the day of its opening, Magistrate Frederick B. House said, "This court will be a clearing house for all kinds of fatal accidents and deaths, and will reach two of our greatest evils: the selfish, reckless driver, who is no better than a murderer, and the pistol carrier, or gunman."

During World War II the old building became headquarters for the city air raid wardens and the civilian defense office of the police department. On January 10, 1942 The New York Times reported, "It is planned to give lectures to classes of 200 to 300 air raid wardens at a time in the new headquarters."

By the time photographer Cyrus Townsend Brady, Jr. took this photograph, the lampposts had been removed. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

The old Police Headquarters building was converted to a courthouse in March 1946. Three new courts opened here, the Lower Manhattan Summons Court, the Lower Manhattan Arrest Court and the Downtown Traffic Court. The days of honoring the former President within the building ended on May 10 that year. The New York Times reported that Police Commissioner Arthur W. Wallander "turned over the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Room in the old Police Headquarters Building...to the Home Term Court." The furniture, portrait of Roosevelt and the plaque were all removed.

Just three years later the venerable marble building was demolished for a parking lot. For nearly six decades automobiles parked on the site, most of their owners never knowing the history that had played out there. Then in 2004 a rather nondescript brick apartment building was erected on the site.

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

It was demolished for a parking lot. Where is Joni Mitchell when we need her?

ReplyDelete