photo via westsiderag.com

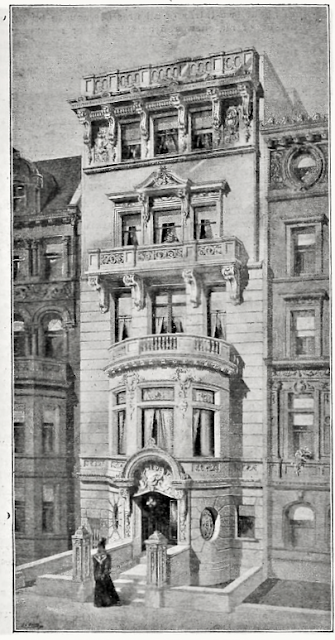

In 1891 developer F. G. Pourne completed a row of nine impressive stone-faced homes at 28 through 44 West 73rd Street. Architect George H. Griebel had designed them in the Romanesque Revival style with elements of Renaissance Revival. They were configured in an A-A-B-A-A-B-A-A-C pattern, the second story oriels of the A models and the three-story bowed bays of the B's creating an undulation of rounded forms.

Rather than ending the row with a third B model, as would be expected, Griebel designed 44 West 73rd Street as an architectural step-sister. It was narrower than the others at 17-feet wide, and the sharp angles of its full-height projecting bay starkly contrasted with the gently bowed bays and oriels of the other houses.

Things did not start out well for the house. Only months after the new owners moved in, on June 23, 1892, The Evening Telegram reported that 44 West 73rd Street would be sold at foreclosure auction the next day.

It became home to the Moritz Doob family. Born Moises Dub in Czechia (today the Czech Republic) in 1847, he was variously known as Moises, Moses and Moritz. At some point after arriving in America his surname became Doob.

Doob was the principal of M. Doob's Sons & Co. at 540 Broadway, an embroideries manufacturer. He and his wife, the former Henrietta Mork, had five children: Mork Menasseh, Irving Ephraim, Hugo, Anah (sometimes spelled Annah) Henrietta, and Valerie Stephanie.

The weddings of wealthy Jewish families often took place in high-end hotels or restaurants. Such was the case on April 2, 1903 when Anah Henriett was married to Dr. Samuel Joseph Kopetzky at Delmonico's. The dashing groom was a captain in the National Guard and had served in the Spanish-American War. The New-York Daily Tribune wrote, "The rooms were prettily decorated with American Beauty roses, flowering plants and palms. The room in which the ceremony was performed was decorated with white roses and orange blossoms."

Still living in the 73rd Street house with their parents at the time of the wedding were 25-year-old Irving and 16-year-old Valerie. Young ladies of Valerie's social status received their educations in private schools or abroad. Valerie accompanied her parents to Europe for that purpose the following year. On April 10, 1904 the New York Herald explained that the Doobs "sailed for Europe recently, where they will spend several months. Miss Doob is to remain abroad for two years, completing her studies in Switzerland." Valerie returned to 44 West 73rd Street in 1906.

Like all wives of well-to-do businessmen, Henrietta involved herself in charitable work and was a member of Jewish Charity, among other causes. She and Moritz enjoyed society entertainments and upscale restaurants.

On the evening of December 20, 1911 the couple attended the Metropolitan Opera. As they found their seats, Moritz helped Henrietta out of her coat. As he did so, her gold bracelet slipped off with the garment. It was not until they got home and she began removing her jewelry that Henrietta realized the heirloom was missing. It is unclear whether her advertisement to recover the lost bracelet was successful in retrieving it.

Anah and Samuel Kopetzky were living in Ohio by now. They had two children, six-year-old Karl Abraham and four-year-old Yvonne Anah. Earlier that year Yvonne's nurse either left or was fired. Henrietta seems to have insisted on interviewing the replacement servant who would be taking care of her granddaughter. She placed an advertisement on August 30 that sought:

A refined German nursery governess to go to Cincinnati to take entire charge of one child of 4 years; North German preferred. Inquire 9-12, 44 West 73d.

And as long as she was looking for a servant for her daughter, she placed an advertisement for herself. On the same page an ad sought:

A well recommended parlor maid and waitress in private family; no chamberwork. Inquire 9-12, 44 West 73d

Valerie was 26 years old in 1913 when her parents announced her engagement "to Dr. I. E. Friedmann, of Berlin, Germany." Ignatz Ernst Friedmann would not remain in Berlin with his bride, instead relocating to New York City.

But Valerie would return to Berlin--as an opera singer. Nine years later, on September 24, 1922, a cable from the New York Herald's bureau in Berlin read, "Mme. Valerio Doob Friedman of New York and her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Morris Doob, sailed for home following Mme. Doob's success in Mozart's opera, 'Il Seraglio,' at the new People's Opera."

The West 73rd Street house had been sold in March 1920. It changed hands at least once before H. L. Gates and his wife moved in. Gates was born in Columbus, Ohio in 1884 and studied at Ohio State and Cornell Universities. A long-time journalist and editor, he had held positions with such far-flung newspapers as The Shanghai Times in China; The Daily Sketch, the Evening Standard; and Gazette and Graphic in London; and the San Francisco Call. In New York he wrote for the New York Herald Tribune, was associate Sunday editor for The New York American and wrote Sunday features for The New York Times.

Gates retired from the newspaper business in 1925 to devote his time to writing fiction. The New York Times said "He wrote novels of romance, mystery and the West. Some of these were adapted for the movies." The prolific author wrote 52 novels before his death while living in 44 West 73rd Street on March 12, 1937.

In 1953 the house was converted to apartments and furnished rooms. Among the tenants in 1961 was 33-year-old Sophie Oland, who had a 1-1/2 room apartment. She had come to New York from Puerto Rico in 1948 and had worked for a garment company since then.

On April 30, 1961 a dogwalker discovered Sophie's body laying face down in an irrigation ditch near Flushing Airport. There were no signs of violence, and no traces of drugs or alcohol. The Long Island Star-Journal reported, "Police found few clues to her life in the apartment. It contained only her clothes, a few pieces of inexpensive furniture, several religious pictures and some stuffed toys and dolls." The theory was that "she could have died naturally in a car and a frantic 'friend' pushed her body into the marsh land," said the newspaper.

In 1964 the history of the Doob house took a bizarre turn. That year Frances Voyticky acquired it from Jean Rudiano. The city began foreclosure proceeding in 1971 and Diana Haslett-Rudiano, Jean Rudiano's widow, purchased it in 1975 while it was still in foreclosure.

According to Haslett-Rudiano, it was a emotional purchase, since her late husband had owned the building. The emotional connection was, however, not deep enough to maintain the structure. Plans for alteration were filed in August 1983 and scaffolding and construction netting veiled the building. And it would remain there for decades.

In 2015 a representative of the West 73rd Street Block Association complained that the house had become a "haven for rats." The association's president, Judith Bronfman, told NY Press, "We've gotten inspections by the Fire Department, the Department of Buildings, the Department of Sanitation, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, but the garbage then gets cleaned up, sort of; the minimal fines get paid, and then all that busy ineffectual activity joins the news stories in the archives."

Rather astoundingly, at the time of this writing the scaffolding and netting are still in place, and according to a neighbor the windows are never closed, letting the rain pour in. There is no clear evidence of on-going work. It is a humiliating situation for the once-proud home of the wealthy Doob family.

photograph by the author

many thanks to reader Beth Goffe for suggesting this post.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog