from the collection of the Library of Congress

In 1783 the war with Britain was over, but financial conditions for the fledgling United States were nearly chaotic. Continental currency, which had become worthless, ceased to circulate. While the Government authorized paper currency, states issued bills of their own.

The need for standards and organization was crucial. An editorial appeared in the New-York Packet on February 12, 1784 proposing the establishment of the Bank of the State of New York, and laying out the advantages of such an institution. With a slightly different name, the Bank of New York would be headed by a governor and six directors, who served without compensation until the bank was stable enough to pay its first dividend.

The constitution of the Bank of New York was written in March 1784 by Alexander Hamilton. The institution's first home was in the magnificent William Walton mansion on St. George's Square (later Franklin Square). The directors rented the house until 1787, when the bank moved to 11 Hanover Square. By 1796 it required a larger facility, and in November the directors purchased the house of William Constable at the corner of Wall and William Streets.

The 1797 building sat within an elegant residential neighborhood. To the rear, on William Street, can be seen a portion of the Phillips mansion, and to the right is General John Lamb's residence. from the collection of the New York Public Library.

The cornerstone of the new building was laid on June 22, 1796 and the bank opened in its new home the following year, in April. For six decades the palatial structure served the bank. But, according to bank historian Henry Williams Domett in 1884, "The need of better accommodation for the business of the bank had long been felt, and in 1856 a committee had been appointed to procure plans for a new building."

The architectural firm of Vaux and Withers was commissioned to replace the old structure with a modern building. The bank temporarily moved to rented space at William Street and Exchange Place, and the old building demolished. The cornerstone was laid on September 10, 1856 and construction was completed in March 1858 at a cost of $173,400--more than $5.6 million in today's money.

Henry Williams Domett wrote:

The structure was described at the time as 'built in the Italian style, of Little Falls brown stone and Philadelphia brick. The banking-room is fifty-eight feet long, thirty-five feet wide, and twenty-six feet high, occupying two stories in the central and rear part of the building. The ceiling and walls, and the whole fitting-up of the interior compare favorably with the elegance of the exterior, and the room is lighted on the east side, where it adjoins the present American Exchange Bank, by glazed panels in the ceiling.

The original Vaux & Withers structure was four stories tall. image from Martha J. Lamb's Wall Street in History, 1883 (copyright expired)

The New York Times gave the building a mixed review. An article on March 26, 1858 said, "The style shows great invention latent in the architect, and though it is most elaborately ugly in its details, the general effect is by no means unpleasant." As unhappy as the critic was of the exterior, he was impressed with the interior. He called the banking room "a beautiful apartment...lined with Caen stone, and finished with dark oak," and said, "The best taste has been exhibited throughout in the fittings up and in the smaller offices." The article noted that the marble cornerstone from the 1798 building was inserted into one wall.

The Bank of New York was in its new home only three years before civil war broke out in the South. On April 28, 1861, just two weeks after the first shot was fired upon Fort Sumter, the bank's president, A. P. Halsey approved a loan of $50,000 to the United States Government "for equipping volunteers." The amount would top $1.5 million today.

In the summer of 1863 an Irish cleaning woman, Honora Barry, visited the offices of three separate brokers on Chatham Street. She had $300 in bank notes--more than $6,300 today--and she most likely thought that by dividing it into smaller amounts she would draw less attention. She was wrong. On August 5, The New York Times reported that she had been arrested "on a charge of stealing a package of bank bills" from the Bank of New York. The article said, "The woman was employed in taking care of the premises at No. 48 Wall-street, and states that she found the money in the cellar."

The Bank of New York continued to grow, and in 1879 the firm of Vaux & Radford was called in to enlarge it. The renovations, which cost the equivalent of $1.5 million today, resulted in two extra floors, one in the form of a fashionable mansard crowned with lacy iron cresting. A safe deposit vault was installed in the basement, the outer door of which weighed three tons.

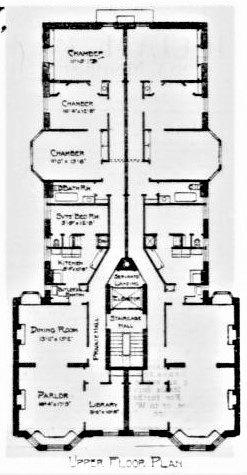

from A History of the Bank of New York, 1784-1884, by Henry Williams Domett, 1884 (copyright expired)

Extra space in the upper floors was leased as office space. Among the residents in 1885 were attorney George B. Newell, and architect Thomas Stent.

It appeared in the summer of 1908 that the vintage building was doomed. On August 1 the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that Clinton & Russell had been commissioned to design "a high office building to be at least twenty stories" on the site. But the idea stalled and, instead, in July 1913 architects Marc Eidlitz & Son made "general alterations."

Nine years later, on June 20, 1922, The New York Times reported on the merger of the Bank of New York and the New York Life Insurance & Trust Company, "two of the oldest financial institutions of the United States." The article noted that "for the immediate future," the business of the two institutions would be conducted from their present locations.

The "immediate future" was short lived, at least for the venerable Bank of New York building. In November 1922 the architectural firm of Clinton & Russell was hired to design a replacement skyscraper for the Bank of New York and Trust Company on the site. But, as had been the case in 1908, the firm would be disappointed. The commission was given, instead, to architect Benjamin Wistar Morris. The new 32-story bank building was completed in 1929.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog