In 1886 Finance and Industry noted "The name of L. Schepp has become a household word throughout the United States." Leopold Schepp had come a long way in his journey to become a "household word." He had started his career in 1851 with 18 cents his mother gave him. He bought a dozen palm-leaf fans for 1.5 cents each, and then sold them on the Third Avenue street cars for 5 cents. He later said "They sold so fast that the third day I hired three other boys on commission and soon I was making $15 a week." By 1871 he had established the importing firm of L. Schepp & Co., and two years later focused his attention on coconuts--a food item mostly overlooked in America.

Schepp made the ungainly coconut both marketable and convenient by developing a process of drying and shredding it. Finance and Industry explained "his excellent process renders the meat of the cocoanut more easily digestible, and is the only party that has made the process of business a success." Sold in tins, his desiccated coconut made him a fortune and he essentially cornered the coconut market in America.

On March 23, 1880 Schepp purchased the five buildings which made up the northwest corner of Duane and Hudson Streets. Within the month architect Stephen Decatur Hatch filed plans for "one eight-story and mansard roof brick store." The projected cost, $150,000, coupled with the $45,000 Schepp had paid for the site, brought the project to nearly $4.75 million in today's dollars.

|

| sketch from Finance and Industry, 1886, (copyright expired) |

Although Schepp leased out some space--candy makers Green & Blackwell signed a nine year lease in 1882 for instance--his massive operation required nearly the entire building. He employed about 150 workers in the Duane Street factory, and each of his ships carried from 300,000 to 500,000 coconuts at a time from Central America, where he operated 21 "trading stations."

Interestingly, Schepp did not pay for his coconuts; the natives who harvested them had no use for currency. Finance and Industry explained "there are several thousand Indians, whom he supplies with the necessaries of life through the various trading-posts, they giving him in return cocoanuts, ivory nuts, tortoise shell, cocoa, coffee, etc." (The additional items created a side-line, of sorts, and Schepp sold the raw tortoise shell for as much as $6 per pound.)

|

| Schepp's tins and advertisements routinely featured playful monkeys, as on this trade care. |

That temper came into play in 1889 when the Colombian Government began interfering with American trade. It started on October 2 when the gunboat La Popa seized The Pearl, a schooner owned by New York City merchant James Herron. "She was taken to Carthagens and held subject to confiscation for smuggling," reported the Pittsburgh Dispatch.

Shortly after The Julian was overtaken and towed to Carthagens, "and there she now lies, with her captain and crew prisoners," and when Foster & Co. sent a second vessel, the Edith B. Coombs, to retrieve its perishable cargo, that ship, too, was captured.

Although the State Department began diplomatic negotiations, Leopold Schepp had no time for that. On January 1, 1890 the Pittsburgh Dispatch reported "The firm of L. Schell & Co., importers...has declared war against the United States of Colombia. At least, they have sent an armed vessel to Colon and the coast of Panama, with instructions to make forcible resistance if the gunboat La Popa, which recently seized several trading vessels, should attempt to interfere with her."

The article continued, "L. Scheff & Co. have promptly taken the law into their own hands, without bothering with the slow processes of the State Department at Washington." Schepp outfitted the firm's schooner George W. Whitford with "two cannon, rifles and revolvers and plenty of ammunition." The show of force worked. At least for now.

Just when Schepp most likely felt things were back to normal, the George W. Whitford was seized by Colombia on March 31, 1896. As Washington negotiated, Leopold Schepp blamed his own Government allowing the thuggery. On April 15 The Sun reported "Mr. Schepp said last night that only vessels flying the American flag were subjected to insult and annoyance by the Colombian Government. This was due, he said, to the fact that the war ships of other nations, principally of Germany and England, frequently appeared in Colombian ports, whereas an American man-of-war was almost unknown." Schepp added "We trust the day is not far distant when we will have a navy large enough to command respect in Central American for vessels that fly the American flag."

The George W. Whitford was finally released on April 20; but Leopold Schepp was still fuming. He told reporters the following day that he intended to "demand indemnity from the Colombian Government" for his expenses and lost goods.

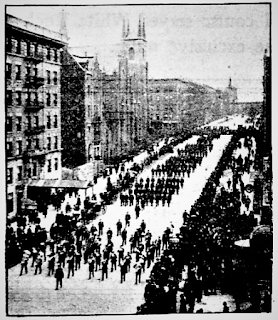

|

| from the collection of the New-York Historical Society |

On April 14, 1909 The Sun reported "They apply to Leopold Scheff an assortment of adjectives, among which are 'overbearing, exacting, domineering and insolent.'" When, they asserted, they had disagreed with him in the meeting, he said that "until they should comply he would use his full power, force, potency and influence to oppress, coerce, overbear and compel them do to so."

Among the items with which they took issue was the Schepp Building itself, still personally owned by Schepp. "The complaint says that Mr. Schepp stated that the corporation should and would buy the property from him at $600,000 and that he told the plaintiffs that if they opposed the sale they would be forced out of the company." The men described it as "antiquated and rated in the lowest class by the Building Department, and classified by underwriters as a 'fire trap.'"

Schepp characterized his former employees as "exceedingly ungrateful."

Following World War I the wholesale shoe district was taking over the immediate neighborhood around the Schepp Building. At the same time the L. Schepp & Co. operation was scaling back. In 1920 Rich & Hutchins, Inc., wholesale shoe dealers, leased five floors--half of the building--including the ground floor stores.

Leopold Schepp was 83-years old in 1925 when he decided to distribute his massive fortune now, rather than after his death. On March 16 he handed an office boy a check for $500. The head stenographer, who had been with the firm 14 years, received $3,000. Another got $1,000 and the loyal clerk who had served Schepp for 21 years received $5,000, the equivalent of $67,500 today.

Two days later Schepp announced his intention to spend $2.5 million to establish a foundation for New York boys between 13 and 16 years old that would provide them "with means to prepare themselves for useful careers." The boys would be required to "pledge themselves to abstain from bad habits, to obey the laws of the State and nation, and to be considerate in their treatment of others." If, after two years, they kept the pledge, they would receive $200 to be used to either start a business or finish their educations. By October he had funded $4.5 million to his Schepp Foundation for Boys.

The publicity produced unexpected ramifications. On July 23, 1925 The New York Times ran the headline "Thousands Swamp Schepp With Pleas / Philanthropist Decamps to Escape Army Seeking to Spend His Money." The article said "When clerks came to open the office at 8:30 they had to make their way through a throng of money-seekers at the door. Five telephone trunk wires were jammed all the forenoon with calls from persons who wished to convince Mr. Schepp that he could find no better mark for the benefactions than themselves."

Bags of mail contained thousands of letters from across the country. A separate office was leased and a "corps of secretaries" was hired, tasked with manning the phones and reading through the "great heaps of communications." The Times said "Letters and telegrams were arranged under the following classifications...1. Bona fide suggestions 2. Needy poor. 3. Young men requesting money for college education. 4. Job seekers. 5. 'Nuts' and 'cranks.' 6. Charitable institutions seeking additional endowment, to which Mr. Schepp already has said he did not intend to contribute.

Requests included one from a 40-year old woman who wanted $4,000 to "persuade her beloved to marry her," an undertaker who needed a new hearse, a request for a "fund for middle-aged spinsters 'better to maintain their accustomed position in life, their self-respect and their happiness,'" and dozens from people who said they had been swindled.

Leopold Schepp died following a mild stroke on March 11, 1926. The following year a renovation and modernization of the Schepp building was done. It was most likely at this time that the outdated, Victorian mansard tower was removed. Just months later a structural failure created a dramatic and dangerous situation.

In 1930 the operations of L. Schepp & Co. were noticeably curtailed. Employees worked only four days a week; a situation that most likely saved lives on June 27. At 11:00 that morning a 20,000 gallon water tank, weighing about 200 tons, crashed through the roof and continued through the tenth and ninth floors. A flood deluged the lower floors where about 100 men and women were working. Amazingly, no one was injured.

"Workers on the lower floors were startled by a dull rumble that suddenly changed to a thunderous roar as the huge tank crashed through the roof of the building and dropped to the ninth floor, twisting girders in its path," reported The Times. "The workers fled to hallways and stairways, and were thoroughly soaked before they reached the street." Two men were taking a load of coconut to a freight elevator when the shaft turned into a "miniature Niagara." The newspaper said "When they ran out to the street, shouting for help, they were covered with shredded cocoanut and dirt and passersby got the impression that they had been tarred and feathered."

Department of Buildings investigators found two other water tanks "tilted at precarious angles." Only a year after the substantial renovations the building had to undergo extensive work again.

|

| The 1927 update left a blunt tower blunt and considerably diluted the building's personality. photo by Edmund Vincent Gillon from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

In 1937 L. Schepp & Co. ceased operation. By then the building had a variety of smaller tenants. One, the Central Machinery and Supplies Company was indicted in June 1936 in a conspiracy to sell counterfeit automobile parts. In 1940 the newly-formed publishing firm of Burstein & Chappe moved in. That year it published seven books including one novel, a single-volume encyclopedia, and a "popular home medical book." By 1945 Allied Carbon & Ribbon Mfr. Corp. was in the building, flexing its wartime patriotism with the slogan "Allied for Victory!"

Central Machinery and Supplies was not the only tenant that would find itself on the wrong side of the law. On February 18, 1959 The New York Times reported that Seymour Eichengrun and Abe Siegel, vice president and president respectively of the Star Looseleaf Company had pleaded guilty for providing a $700 bribe to Robert Breshlian, business agent of Local 210, International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Assistant U.S. Attorney Donald H. Shaw said the money was for "advice and union favors."

The last quarter of the 20th century saw the Tribeca renaissance arrive at No. 165 Duane Street. In 1977 Bragr Times regularly staged poetry readings here. And in 1981 the upper floors, where coconuts for decades had been dried and shredded, were converted to apartments.

The Schepp Building received star status when chef David Bouley opened his French Provencal-style restaurant, Bouley, at street level in August 1987. The famous destination restaurant would remain in the space until 1996. It was replaced in 1999 by the Northern Italian restaurant, Scalini Fedeli New York,

In the meantime, a half-million dollar restoration of the roof was initiated in 1991. The project, headed by architect Kevin Bone, focused on the slate roof and dormers. Sadly, restoring the lost mansard tower was not in the budget.

That same year the building played a part in the emerging Gay Rights Movement. The co-op board refused to allow two unmarried men to co-own an apartment. The applicants sued, charging the board based their denial on their being "unmarried and homosexual." The city's Human Rights Commission agreed, saying "probable cause existed to credit the allegations." As a result, the board expanded its definition of "spouse," to include "domestic partner."

There are just four apartments per floor in the sprawling Schepp Building. While it still commands attention after more than 135 years; its wonderful corner tower is a significant missing piece.

photographs by the author

.png)