In January 1888 ground was broken for an ambitious row of ten upscale homes at Nos. 601 through 619 West End Avenue, between 89th and 90th Streets. The architectural firm of Thom & Wilson was well known for its residential work on the Upper West Side, but this project was personal. Partner Bernard Wilson had purchased the plots and doubled as the developer.

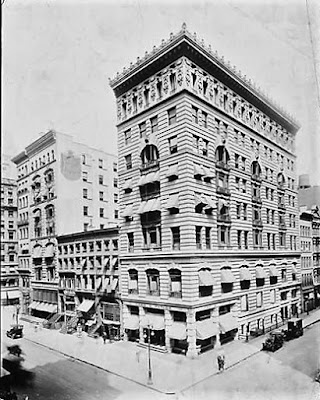

Construction was completed that October. Thom & Wilson had created highly ornamented Renaissance Revival brownstones, each four stories above the high English basement level. Like its neighbors, 615 offered a profusion of visual delights. The box stoop took three turns before arriving at the arched entrance. The broad, parlor window was broken by a carved talemon below a stained glass fanlight. A bowed oriel distinguished the second floor; while above Renaissance style carvings enhanced the pilasters and spandrel panels of the third and fourth floors.

|

| The complex stoop was Escher-like in its angles and directions. |

The original owner fell on hard times as the century drew to a close. On June 6, 1898 the house was sold at foreclosure, with an outstanding balance of more than $25,000 due. The new owners were were a complex, unusual, and uneasy family group.

In the early decades of the 19th century the Jenkins family lived on a sprawling estate in Harlem area, then peppered with farms and summer estates. George W. Jenkins, a commander in the U.S. Navy, and his wife Charlotte had two daughters, Margaret and Sarah. Charlotte, who held title to the property, died in 1862. Her will included a demand which would prove uncomfortable at best for her family.

George would receive income from her estate "as long as he remained unmarried and that he and the children were to live together in the Jenkins homestead." The arrangement proved workable until Margaret married Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Kopper, of the 71st Regiment, in the early 1880s. The New-York Tribune described him as "tall and well proportioned and looks every inch a soldier."

In order to maintain his new wife's interest in what The Evening World described as "the vast Jenkins estate" which "embraced a large part of Harlem," Kopper had to move into the family's home with his father- and sister-in-law. The newspaper later explained "Shortly afterward the marriage Commander Jenkins died."

Colonel Kopper was not only every inch a soldier in his regiment, but also in the Jenkins homestead. Nearly 20 years later Sarah admitted that he "kept the household in constant terror" and "soon had the management of the entire estate in his hands."

Margaret relinquished all control of her portion of the properties, and her husband bullied Sarah into signing papers to sell of portions of the Harlem estate against her mother's final wishes. She would tell officials later that he frequently placed papers before her and forced her to sign them at the "point of a loaded revolver."

By the time Sarah purchased 615 West End Avenue at the June 1898 foreclosure auction, Margaret and Frederick had three children, now young adults--Minnie, E. Caroline, and Frederick Jr. Four months earlier the USS Maine was sunk in Havana Harbor, resulting in the United States sending troops to Cuba. Kopper was deployed, initially, to Camp Black, New York, before being ordered to duty in Florida. Frederick Jr. was a private in his father's unit, and he too was sent south.

Margaret and her daughters moved into the West End Avenue house with Sarah, and the women did their parts for the war effort. The New York Times ran a headline "Wealthy Young Army Nurses" and reported that the two Kopper sisters had been accepted as nurses of the Red Cross Society, and "expect to accompany an invading expedition as such either to Cuba or the Philippines." Sarah served as Chairman of the Finance Committee of the Women's Relief Corps of the 71st Regiment.

Frederick Koppel distinguished himself in service, and was "one of the active combatants at San Juan Hill," according to The Evening World. But when he returned, so did the terror he held over Margaret and Sarah.

When he was sued for an outstanding $198 debt in 1901, he claimed poverty and said that Sarah, "supplied all that he needed for clothes and living expenses." Hoping to hide the uneasy situation at home, Sarah supported his testimony. "Miss Jenkins's testimony enabled the Colonel to evade payment," reported The World.

But the horrifying details inside the West End Avenue house became public in 1911 when a creditor sought to recover a $5,597 note which Kopper had forced Sarah to co-sign. On August 12, 1911 The Evening World said the "old debt...bobbed up yesterday in the Supreme Court, [one] which the military man has neglected some fourteen years."

By now Margaret had died and only Frederick Jr. lived with Sarah. Kopper had remarried in 1909 and disappeared, possibly to Vermont or Canada. So Sarah had to explain that she was coerced to sign the note. The Evening World said "Sensational charges are made by Miss Jenkins in her motion to vacate the long standing judgment. The charges related to the Colonel's alleged disposition to wave a revolver in her face and to force her to sign papers and documents, which, she swears, were unknown to her because of fear of the loaded revolver."

Sarah told the court that even after Margaret died and Kopper had remarried, "he came to her home, moved out some furniture and again terrorized the household with his gruff and belligerent attitude." She admitted, according to the newspaper, "A desire to conceal the family tribulations restrained her from exposing the Colonel years ago."

Sarah R. Jenkins died in January 1926. The West End Avenue block had seen astounding change by now. A year earlier the houses at Nos. 607 through 613 were demolished for a 16-story apartment building designed by Rosario Candela. The homes at the opposite side, Nos. 601 and 603, had been replaced in 1916 by an Emery Roth-designed apartment building.

Real estate operator Louis Schwebel purchased 615 in October 1936. Highly active on the Upper West Side, he was best known for operating tenements and rooming houses. In 1940 the house was converted to two apartments per floor on the basement through second floors; and furnished rooms above.

Among the tenants here in 1954 was Thomas Netterville, who worked as the night manager of the Bickford's cafeteria at 390 East Fordham Road in the Bronx. The chain of Bickford's restaurants was organized in 1921 and by now was a familiar presence throughout New York City. Netterville would be witness to a brutal murder early on the morning of November 20.

Just after 5:00 a couple parked their automobile outside and the man entered the cafeteria to get coffee. While he waited, two young men, 19-year old John Ruggieri and 20-year old Gildo Cuccuru, stopped by the car and "made insulting remarks," according to The New York Times.

The man left to tell the thugs to leave her alone. They followed him back inside where they turned their aggression to him. When Thomas Netterville attempted to intervene, he was knocked to the floor.

It was about this time that the morning manager, Patrick Crotty, arrived to relieve Netterville. He, too, tried to intervene, but was also overpowered. "After he was knocked to the floor, a sugar bowl was hurled at close range at his head," reported The New York Times. "His skull was fractured."

Crotty died on the floor of the cafeteria and his assailants were arrested shortly afterward. They were charged with homicide and held without bail.

|

| The second floor retains original details like the delicate plasterwork and inlaid floors. photo via StreetEasy |

Squashed between soaring apartment houses, the Jenkins house contains two apartments today. Considering its use in the second half of the 20th century, a surprising amount of interior details survive.

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com