On August 8, 1912, a workman is repairing damage to the building caused by the ongoing subway construction. from the collection of the New-York Historical Society.

On October 17, 1850, the newly-formed Pacific Bank opened at the corner of Broadway and Grand Street. The New-York Tribune commented, "The high standing and mercantile acumen of the gentlemen connected with the institution will give it the fullest confidence of the public. We trust it will have a long and prosperous career." The success of the bank was such that in 1858 it erected a three-story brick building a few doors to the north at 470 Broadway.

While the bank operated from street level, offices on the upper floors were leased to tenants like the A. F. Hatfield real estate firm, and the Pacific Insurance Company. Around 1862, esteemed architect Griffith Thomas moved his office into the building. Described by the American Institute of Architects years later as "the most fashionable architect of his generation," he had already designed important structures like the Fifth Avenue Hotel and the St. Nicholas Hotel.

As the Pacific Bank's business expanded, so did its need for larger quarters. In 1871, demolition of 470 Broadway commenced to make way for a new structure. It ended in a tragic accident. On June 18, the New York Herald explained the mishap. "The building was being demolished...The contractors having the work in charge considered the [front] wall safe." They sent a group of men, two of whom were young German immigrants, to the third floor. The New York Dispatch reported, "one of the side walls fell in on a number of the men who were cleaning bricks on the third floor, and partially buried them."

One man, named John Kress, suffered a broken leg, and another, 19-year-old Theodore Hoffner, "had his hip dislocated, and was injured internally." They were taken to Bellevue Hospital while the other men were treated on the site. Tragically, the following day, as reported by the New York Herald, Hoffner "who was so terribly injured at 470 Broadway on Friday afternoon, subsequently died in Bellevue Hospital." One of the contractors, a Mr. Kipler, "took charge of the remains and volunteered to defray all the funeral expenses."

Given that Griffith Thomas's office was still in the building when it was demolished, and that he moved into the completed structure later that year, it is tempting to presume that he designed the new 470 Broadway. Firm documentation as to the architect's name, however, is missing.

The marble-faced, Renaissance Revival style building rose four stories above a rusticated basement level. A high stone stoop rose to the arched entrance of the bank, flanked by Corinthian pilasters, while a second entrance above a shorter stoop provided access to the offices on the upper floors. The second story windows were fronted by blind balustrades and wore dignified triangular pediments. The third- and fourth-floor openings were fully framed, the prominent cornices of the third floor windows providing sills to the fourth. What was most likely a bracketed stone cornice, later replaced by an attic level, finished the design.

Charles Whitman was hired as a bookkeeper by the Pacific Bank in 1849. In 1870 he began a devious scheme by opening an account in the name of "Dwight" and, little by little, depositing small amounts into it. The plan went smoothly for four years. Then, on November 14, 1874, the Evening Post reported that he was "charged with having embezzled nearly $25,000." The small amounts had added up. The amount he was accused of having embezzled would equal about $663,000 in 2024.

In the early 1890s, the upper floor offices were home to firms like P. Goldman's cap and hat factory, here since at least 1887; the Eureka Silk Company; and William Allen & Co., which specialized in printing hotel menus and occupied the basement level. An advertisement on November 9, 1895 for that firm sought a:

Printer, compositor, young man who can change hotel bill of fare; must have some idea of French; must be a pressman and print his own forms. Hotel printing office. William Allen & Co. 470 Broadway, New York.

Edmund J. Wright, who lived in Brooklyn, was manager of the Eureka Silk Company in the spring of 1893. On the evening of April 11, he began to board a Brooklyn-bound L Train when, in the crowd, Peter Murphy "jostled him with his elbow in such a way as to screen the lower part of his person," as reported by The Evening World. The astute Wright felt Murphy's hand on his scarf and immediately realized his diamond pin, valued at $125, was gone.

Peter Murphy had chosen the wrong businessman to rob. Wright already had one foot inside the car, which was about to start. "He dragged Murphy in after him," said the article. Wright held Murphy in the car until it reached the City Hall station, where "the platform man assisted Mr. Wright in removing the prisoner to the street, where he was arrested by Detective Noonan."

A month before the incident, the Pacific Bank suffered a heartbreaking incident. Albert G. Reed was described by The Sun as "an old messenger" who "has been in the employ of the bank for many years." In 1891, Reed began suffering ill health, which caused him to on-and-0ff miss work. The newspaper said, "He was well liked by the bank officers, and, because of his ill health, they decided to send him in the country for a three months' vacation." The kind gesture was misconstrued, however. Reed interpreted it to mean that he was about to be let go, "and it preyed on his mind a great deal."

In mid-March 1893, Reed was ill again, and the president of the bank insisted he take a week off. When Reed returned on March 28, he went immediately to a basement room, likely the boiler room. He sat in a large chair and, "Taking a large pistol from his pocket, one he always carried, he shot himself through the head."

In 1898, P. Goldman and William Allen & Co. were still leasing space at 470 Broadway. The other tenant was the legal office of Charles W. Zaring and Morris H. Beall.

On the afternoon of December 27, Zaring and Beall were having lunch at a restaurant directly across Broadway. One of them noticed smoke pouring from 470 Broadway. The New York Times reported, "They hurried to their office and gathered up a few of their most valuable papers and books, and threw them from a front window to the sidewalk." By now, however, the stairway was engulfed in flames. Happily, a hook and ladder company was already in sight and the men were rescued by ladder a few minutes later.

An iron "bridge" at a rear third-floor window substituted as a fire escape, connecting the building to the rear of 30 Crosby Street. The New York Times described it as "a flimsy affair." But it turned out to be the only hope for the eighteen P. Goldmann employees. By the time they first heard the cries of "Fire!", the halls and staircase were already filled with smoke. Carefully, the group made its way single-file to the Crosby Street building. The New York Times reported, "They had barely reached safe foothold in the other building when the bridge fell with a crash through a glass skylight two stories below."

In the meantime, the employees of the Pacific Bank had carried all the books and cash that were not in the vault to the street. President Hart B. Brundrett swiftly made arrangements with Mills & Gibb next door to use part of its offices and within hours the bank was back in business in its temporary new quarters.

At one point, according to the New-York Tribune, "it looked as though the building was doomed." Happily, after a third alarm was sent in, the inferno was extinguished. The fire damaged was repaired and it is almost certainly at this time that the short attic level was added.

When this photograph was taken, the end of the line for 470 Broadway was on the very near horizon. via the NYC Dept of Records & Information Services.

In an incident astonishingly similar to that of Edmund J. Wright a decade earlier, on April 11, 1903 bank employee William S. Zabriski was on the rear platform of a northbound Sixth Avenue trolley car "when a young man pushed up against him, put his hand in the inside pocket of his overcoat," according to the New-York Tribune, "and took Zabriskie's pocketbook containing $14 and some valuable papers."

As the thief fled at Chambers Street, Zabriskie alerted the other passengers that he had been robbed. Thirty passengers jumped off the trolley with Zabriskie in chase of the culprit. The New-York Tribune wrote, "The man ran in the same direction in which the car was going, and the motorman turned on the current and joined in the chase."

The journalist recounted, "West Broadway hadn't seen so much excitement for a long time. At every corner the pursuing crowd increased in numbers." At one point two policemen, MacVay and Flaherty, joined in. It was Zabriskie, though, who first caught up with the crook, and "had a fist fight with him." James Murray, who was 23 years old, managed to break free, but was soon overtaken by Policeman MacVay, who was able to arrest him only "after a fierce struggle."

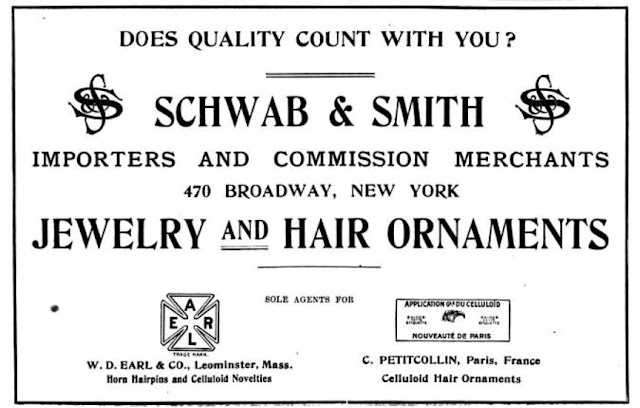

Schwab & Smith moved into the building in 1903. Fabrics, Fancy Goods and Notions, January 1903 (copyright expired)

Around 1927 the Pacific Bank merged with the Irving Trust Company. Its marble fronted building survived until 1939, when it was demolished to make way for a two-story structure, most likely always intended to be temporary, but which remains.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment