Simon and Rosina Weil had lived in the three-story, high-stooped house at 125 East 56th Street since around 1877 when they sold it to Le Grand L. Benedict in September 1901. By then its architecture was decidedly out of fashion.

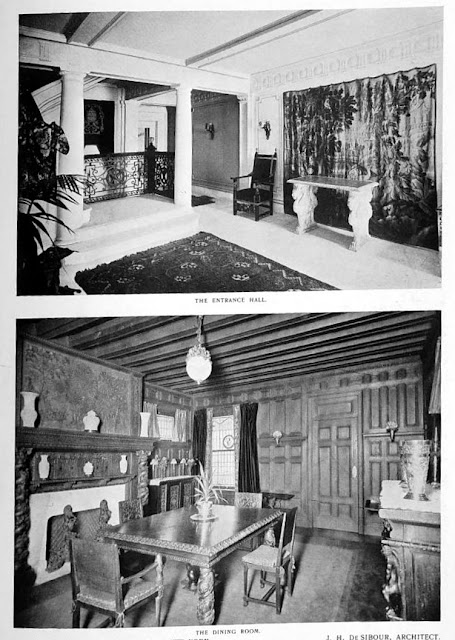

Benedict and his wife, the former Sarah C. Blaine, demolished the vintage house and hired architect J. H. de Sibour to design its replacement. His plans, filed in April 1902, projected the construction cost of the "five story brick and stone dwelling" at $40,000 (about $1.4 million by 2024 terms). Completed early in 1903, the 20-foot-wide house was faced in red brick above a rusticated limestone base. Its Colonial Revival design invoked refined 18th century townhouses of Philadelphia or Boston. French windows on the second floor, or piano nobile, were fronted by faux balconies with waist-high iron railings. The splayed lintels of the third floor and layered keystones of the fourth carried on the colonial motif. The top floor took the form of a tall, single-slated mansard with three pedimented dormers behind a stone balustrade.

Born in 1855, Benedict (whose first name was sometimes spelled LeGrand) could claim an old American pedigree. According to The New York Times, he was "a descendant of a family that came to New England in 1600." He was the son of banker and railroad mogul James H. Benedict. Le Grand and Sarah had two children, Margaret De Witt and Le Grand, Jr. The family's summer home, The Nooke, was in Cedarhurst, Long Island.

The Benedicts' home was completed in time for Margaret's debut. On December 22, 1903, The Sun reported, "Mrs. Le Grand Benedict of 125 East Fifty-sixth street, gave a tea yesterday afternoon at which she presented her daughter, Miss Margaret Benedict, to society...Afterward there was a dinner and the guests went together to Sherry's for the Gorham Bacon dance." Notable among the three young ladies who assisted in the receiving line was Miss Uling Harper.

Uling Harper was the daughter of J. Henry Harper, a partner in the publishing house of Harper Brothers. On March 12, 1905, The New York Times reported, "On Tuesday, Miss Urling Harper...will be married to Le Grand Benedict, Jr., the son of Mr. and Mrs. Le Grand Lockwood Benedict of 125 East Fifty-sixth Street." The article noted that because the Harper family was in mourning, "the wedding will be quiet." Following the ceremony in the Constable Chapel of the Church of Incarnation, the newlyweds made their home with the Benedicts.

In April 1907, the Benedicts sold 125 East 56th Street to Robert Curtis Ogden and his wife, the former Ellen Elizabeth Lewis. Ogden was born in Philadelphia on June 20, 1836. His father relocated the family to New York in 1852 and founded the clothing firm of Devlin & Co., of which Robert became a partner. He and Ellen were married on March 1, 1860.

The couple moved to Philadelphia in 1885 when Ogden became a partner of John Wanamaker. Then, in 1896, he took charge of the Wanamaker Department Store's New York City branch.

Robert and Ellen had two married daughters, Margaret and Julia Tredwell. (A son, Robert G. Ogden, died in 1875 at the age of two.) Margaret's husband was Alexander Purves, and they lived in Hampton, Virginia. Julia and her husband, Dr. George Waldo Crary, lived in the East 56th Street house. The Ogden country home was in Kennebunkport, Maine.

Robert Ogden had served in the Civil War, and had visited the South for Devlin & Co. in 1861. His experience there left a lasting impression. A good friend of Samuel C. Armstrong, who founded the Hampton Institute of Virginia, Ogden involved himself in education in the South, particularly for Blacks. He headed the Southern Education Board and was president of the Conference for Education in the South. Additionally, he provided significant funding to Booker T. Washington and sat on the Governing Board of the Tuskegee Institute. An author, as well, among his works was Getting and Keeping a Business Position.

On November 19, 1909, Ellen became ill. The New York Times remarked, "Before that, for some months, she had been in feeble health." Her condition worsened into pneumonia, and on November 24, the newspaper said that her condition "was said last night to be so serious that she might not live until morning." She lingered until December 3. In reporting her death, the New York Observer noted,

Mrs. Ogden took an active interest in her husband's work for education in the South. She generally accompanied the annual parties of educators he has taken to that field every year since 1901, and was a familiar figure at the numerous educational conference and meetings in which Mr. Ogden has taken a conspicuous part in the later years of her life.

Robert Ogden's Philadelphia friend, George E. Tilge was returning home from Europe with his wife in December, 1910 when he fell ill on board the ocean liner. The ship docked in New York on December 6, The New York Times reporting that Tilge "was in ill health when he left the ship, and went to Mr. Ogden's house." The unexpected house guest died in the East 56th Street house two weeks later on December 18.

Robert Curtis Ogden was in Kennebunkport, Maine on August 6, 1913, when he died at the age of 77. His estate was reported by The New York Times as being "more than $2,000,000." (The figure would translate to about $61 million today.) Margaret inherited both homes. Interestingly, the will forbade the daughters to sell Ogden's horses. It directed, "When they become unfit for use they are to be given to friends who will care for them in the country and provide them with a comfortable death."

Six years later, in March 1919, the Ogden estate sold 125 East 56th Street to Charles Kerkow, "who will use it for his own occupancy," according to the Record & Guide. But despite Kerkow's assertion, he quickly converted the mansion to apartments. Only six months later, on September 24, the New-York Tribune reported that Mrs. Mary E. Green had taken an apartment in the house.

The apartments were extremely high-end. An advertisement for a duplex on December 24, 1922, described it as "unusually decorated and furnished; living room, with balconies, beamed ceiling, cathedral windows, log fire; adjoining a terraced library, 34 feet long, 18 feet high, opening into a sunken garden; breakfast room, bedroom, bath."

Among the residents in 1921 were broker Laurence Craufourd and his wife. The couple's 27-year-old maid, Jeanne Cunningham, disappeared that year along with $5,000 in jewels. As it turned out, the Craufourds were not the only victims of the young woman. Following her arrest in July, she told a heart-breaking story.

A year earlier, Jeanne had met Charles B. Adams in Central Park and "after a flirtation," according to the New York Herald, he got her a job as a maid in his mother's home. Mrs. Adams fired her after a few weeks. Adams convinced Cunningham "on the promise that he would marry her" to steal from her employers. She began a pattern of taking a job, pocketing valuables and leaving that position to repeat the crime at her next position. She turned over more than $50,000 in loot to her lover. Cunningham was crestfallen when she read in the newspapers that Adams had married a society girl. She not only fingered the man who pushed her into criminal activity, but picked him out of a lineup. She told him, "I know you double crossed me. Sorry I had to do this, but I've made a clean breast of it."

Living here at the same time was Mrs. H. E. Aitken. She was summering in Long Island in 1922, when she went to luncheon at the Glenwood Lodge near Roslyn with businessman H. D. Connick. Afterward, she realized she had lost three rings worth $16,000. The New York Herald reported on July 6, "Mrs. Aitken thought she left the rings in the wash room of the lodge. The manager of the lodge said that perhaps a hundred women had been in the wash room between the departure of Mrs. Aiken and her escort after luncheon and their return two hours later." It does not appear that the rings were ever recovered.

The apartments continued to be home to affluent residents throughout the World War II years. In 1967 the lower three floors were converted to offices. The two apartments per floor on the top two survived until 1996, when the building was renovated to office space throughout. Today the Shanghai Commercial Bank occupies the former Benedict residence. The house remains extraordinarily intact outwardly, an astounding remnant of the residential block in 1903.

photographs by the author

many thanks to reader Doug Wheeler for suggesting this post

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

Thank you for all this information. My uncle, William Papworth, owned the buildiing from the 1960s through the 1980s. It was always a treat to visit him at this house.

ReplyDelete