In the 1850's elegant homes rose along Lexington Avenue in the fashionable Murray Hill neighborhood. Typical of them was the 19-foot-wide house at 344 Lexington Avenue, between 39th and 40th Streets. One of a row of identical brownstone-fronted residences, it rose four stories above an English basement. Its Italianate design featured a double-doored entrance beneath an impressive arched pediment, floor-to-ceiling parlor windows, and molded architrave frames around the elliptically arched upper openings.

The house was purchased by Elias William Van Voorhis as an investment property. But, in fact, it appears he never actually enjoyed the rental income. Van Voorhis died in August 1869, and his will explained that for years he had given his daughter, Sarah Ann Brintnall, the rents, and that the "house has been called hers, although the same belongs to me." Interestingly, she did not receive the property outright. It was inherited in equal shared by all the Van Voorhis siblings.

At the time of Van Voorhis's death, the family of Robert McElrath Strebeigh lived here. Born in 1826, Strebeigh and his wife, Agnes, had three children, one of which, Isaac Lefferts Strebeigh, was a freshman at Columbia University in 1869.

The Strebeighs were followed in the house by the Francisco G. Guimaraes family. Sadly, Cecile, the eight-year-old daughter of Francisco and his wife Emma, died on September 18, 1872. Her funeral was held in the drawing room two days later.

The Guimaraeses left seven months later. It was common for well-to-do families to sell their furnishings and start anew when then moved. And so, on April 25, 1873 an auction was held in 344 Lexington Avenue, the inventory of which hinted at the home's elegance. Included was custom-made furniture by Pottier & Stymus (one of the foremost cabinetmakers in the country at the time), "black and gilt Parlor Suits, in red silk; elegant inland Cabinets and Tables, [and] elegant Pier Mirrors." Notable among the inventory was the rosewood grand piano.

The early 1880's saw J. Mills Smith and Mary A. Smith in the house. On January 15, 1883, The Daily Graphic noted that two days later, "J. Mills Smith, of No. 344 Lexington avenue, will give a masquerade party."

Around 1888, Fanny C. and Charles T. Dillingham began renting the house. Moving in with them was Charles's brother, Dr. Frederick H. Dillingham.

Charles was the principal in the large publishing firm and book store, Charles T. Dillingham & Co. He was, as well, a stockholder and director in the New York Amusement Company which owned the New York Baseball Club. But upheaval within the ranks of the players, exacerbated by a catastrophic losing season in 1890, left the club hemorrhaging cash. It resulted in what The Sun called "the disastrous baseball war," and in Dillingham's resignation after he "soon became tired of putting his hand in his pocket."

A graduate of Bowdoin College Medical School, Dr. Frederick H. Dillingham was a specialist in transmissible diseases like typhoid fever and yellow fever. In addition to his private practice, he worked in the city's Bureau of Contagious Diseases as an "inspector of vaccinations." His research is evidenced in a short note to the editors of the North Carolina Medical Journal in December 1888. "I am now using Lactated Food in a case of typhoid fever, where it agrees better with the patient than anything else. It has also proved beneficial in several other cases."

The Dillinghams leased the house through 1891, when it became home to Dwight Townsend and his wife, the former Emily Hodges. The couple had a daughter, Anna Helmet. Born in 1826, Townsend was a direct descendant of John Townsend, one of the three brothers who arrived at Oyster Bay, Long Island, in 1665.

Dwight Townsend made his fortune in the sugar refining firm of Havemeyer, Townsend & Co. He served in the United States House of Representatives from December 1864 to March 3, 1865, and was re-elected in 1871, serving until March 3, 1873.

Dwight Townsend, from the collection of the National Archives at College Park, Maryland.

In 1895, Sarah A. Britnall bought out her siblings' shares of the property, and then sold 344 Lexington Avenue to the Townsends for the equivalent of $731,000 in 2022. Emily entertained frequently. On April 3, 1895, for instance, The New York Times reported, "The last of the four recitals given by William H. Barber took place at the home of Mrs. Townsend, 344 Lexington Avenue," and on February 2 the following year, The Press said Emily's recitals "have been the most exclusively smart musicales of the year."

Dwight Townsend died at the age of 74 on October 29, 1899. Emily remained in the Lexington Avenue house until June 1904 when it was sold to Dr. George V. Foster for $27,500--about $825,000 today. The Real Estate Record & Guide reported that the new owner "will make extensive repairs," before leasing it.

But after the renovations were completed, Foster and his wife, Anna, sold it, instead, to Howard Herrick Henry and his wife, the former Frances Burrall Strong. Henry was the senior member of the stockbrokerage firm Henry Bros. & Co., and a former governor of the New York Stock Exchange.

The Henrys, who had two daughters, Grace and Frances, immediately hired architect Robert S. Stephenson to enlarge the house with a three-story addition to the rear. Construction was completed just in time for Grace's introduction to society. On December 2, 1906 The Sun reported, "Mrs. Howard H. Henry...will give a tea on Friday afternoon, when her daughter, Miss Grace Henry, will be the debutante." The New York Times noted, "The Henrys are descended from one of the old Quaker families of New York, who at one time lived in the great brownstone mansions and villas which were built in the early part of the last century on East Broadway and Rutgers Place." The article added, "Mrs. Henry will give a dance later for her daughter."

On the afternoon of April 8, 1909 Frances attended services at St. Bartholomew's Church. The Sun reported, "She noticed behind her a man who was praying fervently." Frances went to the communion rail, and when she returned to her seat, her handbag and purse were missing--and so was the passionately praying man.

The following day, before Frances had reported the theft, Detective William O'Brien's suspicions were raised when John Curdley, an out-of-work theatrical scenery and property man, attempted to pawn a bag and purse. Upon questioning, Curdley admitted he had stolen them from St. Bartholomew's. In court, he explained to the judge, he "had to steal or starve." He was held on $500 bail--more than $14,500 today--awaiting trial.

Two months after the incident, the Henrys brought back architect Robert S. Stephenson, now with the firm of Stephenson & Wheeler, to renovate the rear addition by altering interior walls.

On October 27, 1912 the New York Herald reported on the announcement of France's engagement to Harvey Graham, "son of Mrs. Hubert Vos and brother of Mrs. Jay Gould." The article noted that Frances was "the sister of Miss Grace R. Henry, one of society's best known amateur playwrights."

It was an unusually long engagement. The couple was married nearly four years later, on May 1, 1916, in St. Bartholomew's Church. Grace was her sister's bridesmaid and a reception was held in the Lexington Avenue house afterward.

Another notable incident for the family happened a few months later. On September 11, The New York Times reported, "Photographers have completed the film for the moving picture play, 'The Treasure of the Inca,' which will be presented in the entertainment, 'The Lenox Follies of 1916'...The drama was written especially for the Lenox colony by Miss Grace R. Henry."

Howard Herrick Henry died in the Lexington Avenue house on March 31, 1917 at the age of 60. Five months later, on August 3, the New York Herald announced, "The future home of Mrs. Howard H. Henry and Miss Grace R. Henry, who have lived at No. 344 Lexington avenue for several years, will be at No. 46 East 64th street."

With the United States drawn in to World War I, Frances leased 344 Lexington Avenue to the Junior Officers' Club. The organization would remain throughout the conflict.

Although she never again resided in the Lexington Avenue house, Frances Henry was still concerned about the neighborhood. On April 15, 1921, The Evening World reported, "A number of old Murray Hill families appeared before the Estimate Board and protested against changing from a residence to a business district under the zoning law, both sides of Lexington Avenue from East 39th Street to a point midway between East 40th and East 41st Street." Among the vocal opponents, said the article, was Frances B. Henry.

At the time, she was leasing the house to John Russell Taber, described by The New York Times as a "millionaire maker of decorative marble." The newspaper said "Mr. Taber, known for many years as the 'Marble King,' had been deaf, and blind in one eye for some time." The elderly man shared the house with his unmarried daughter, Marion, who was secretary of the State Charities Aid Association, and was in charge of the occupational therapy work at Bellevue and Fordham Hospitals.

On the night of October 31, 1922, the 78-year-old Taber attempted to cross Park Avenue at 78th Street. He was hit by a cab and taken to Bellevue Hospital where he died the following day.

Frances Henry died in 1924. The Lexington Avenue house saw several owners over the next decade until, as Frances Henry had feared, it was converted to a store in the basement level and furnished rooms above. The stoop was removed and the residential entrance removed to sidewalk level. Surprisingly, while the carved frames of the upper windows were shaved flat, the exuberant, original entrance was kept intact. Even the double doors were preserved, which now opened onto a tiny railed balcony.

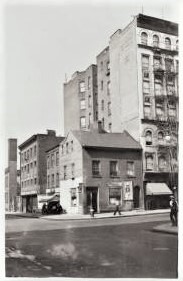

The original appearance of the upper floor windows can be seen in the once-identical house next door. via the NYC Dept of Records & Information Services.

Trouble came in 1978 when police raided the former parlor floor. On May 12, The New York Times reported, "Eighteen persons were arrested last night...in what police said was a $50 million-a-year gambling operation controlled by the Vito Genovese crime family." The article said, "One of its sites--on the second floor of 344 Lexington Avenue--had the most sophisticated gambling equipment they had ever seen, police said."

In the early 1980's the ground floor space was home to Scheherezade, a French continental restaurant. It was replaced around 1987 with Christine's Polish Restaurant. On May 4 that year New York Magazine said, "There's nothing particularly elegant about this place, but it does serve three kinds of borscht, and the food is good, and cheap." A third regional restaurant, the Bombay Grill, opened here around 2007.

In 2009 a sidewalk shed was erected at 344 Lexington Avenue. It remains there thirteen years later. Peeling paint flakes from the timeworn brownstone facade, and yet, above that sidewalk shed, the handsome 1850's entranceway still recalls when wealthy New Yorkers once lived here.

photographs by the author

many thanks to reader Matt Kay for requesting this post

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)