|

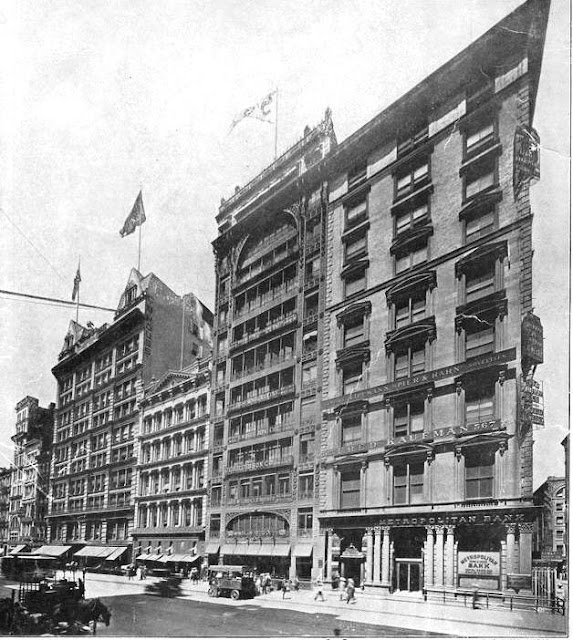

| The four-story 1893 brick addition deftly mirrored the original marble structure below -- photo by Alice Lum |

By 1860 the fashionable shopping district of New York had migrated northward to the blocks on Broadway just south of Houston Street. The magnificent St. Nicholas Hotel engulfed the entire block between Broome and Spring Streets and upscale merchants built impressive structures to lure wealthy shoppers—Tiffany & Co. had already been at 550 Broadway for nearly a decade.

It was time for Tiffany’s rival, Ball, Black & Co., to move north from 247 Broadway as well. Among other articles, the company produced and sold jewelry, silver objects, clocks, decorative furniture and chandeliers. Founded in 1810, the company was originally located at 166 Broadway and was considered the jewelry store of New York City. As its successful business grew and as commerce moved northward up Broadway, the store had changed addresses three times. Ball, Black & Co. was ready to move again.

John A. May was a manufacturer of umbrellas, but he dabbled in real estate as well. In 1860 he commissioned architect John Kellum to design a building specifically for the use of Ball, Black & Co. Completed a year later, it was a six-story show-stopper of East Chester marble.

Kellum craftily set the sixth floor back from the vision line so that it was invisible from the street, creating the necessary, classic proportions. In 1868 William Leete Stone described the building as “magnificent” and “justly ranking among our finest specimens of architecture.”

|

| Well-dressed shoppers peer into the enormous plate-glass windows in the 1860s. |

The store was opened on July 1, 1860 “with great splendor and éclat.” The structure was not only beautiful, but innovative. Touted as the first “absolutely fire-proof” building in New York, the vaults below street level contained the first safe deposit system in the United States. The single-sheet panes of plate glass imported for the first floor windows—14 feet, 8 inches tall and 9 feet, 2 inches wide—were thought to be the largest ever made. Certainly they were the largest ever brought to the U.S.

Steele wrote “In proportion, in chasteness of design, in rich and elegant finish, and in perfect keeping, we know of no building in the whole length of Broadway that can equal it…The first story is pure Corinthian, carried out in its details from the base to the summit of the entablature. The upper stories are Italian, but so ornamented as to be in keeping with the main story and to give a pleasing uniformity to the whole structure.”

The entrance doors were designed so that when opened they would form decorative sides to the vestibule. They boasted carved moldings and green bronze rosettes, designed to the specifications of Ball, Black & Co. Inside, the “Grecian style predominates, and is treated in a rich, chaste and original manner,” reported Steele. “The fittings, which are very beautiful, are composed of panels of rightly-stained wood and gold. A series of cabinets extend along the south wall, forming one continuous design by means of arches, under which are elegant vases. The whole appearance is rich and elegant in the extreme.”

The first floor was exclusively for the sale of jewelry—diamonds and other gems, watches and silverware. Ball, Black & Co. advertised that the “stock of diamonds in this store is among the largest in the world, offering a vast selection of the costliest gems of the finest water and the rarest cutting.”

A marble staircase took the shopper to the second floor where artwork and clocks were displayed. Steele reported on “a gallery of fine paintings, rare specimens of the Italian, Flemish and German schools” and “a wilderness of rich clocks, bronzes, marble statuary, and splendid mantel ornaments of every kind, together with superb porcelain ware of Sevres, Dresden, and Berlin Royal Manufactories.”

On the third floor could be found chandeliers and gas fixtures. Many of these were manufactured on the premises while others were imported from France and England.

The top three floors housed the manufacturing and workroom spaces. Jewelry was made here, diamonds set, watches repaired and tableware was gold or silver plated. The company employed over 300 works including designers, engravers, chasers and modelers.

|

| Ball, Black & Co. designed and sold handsome silver ware like this coffee pot. |

Two years after opening the new store, Ball, Black & Co. hinted at the wide array of merchandise in the store in an advertisement in Round Table. The ad listed “rich jewelry, silver ware, watches of all first-class makers, Parisian bronzes, clocks and mantel ornaments, cabinets, pedestals and mosaic tables, etc., rich assortment of chandeliers and gas fixtures, extensive collection of modern oil paintings of the most celebrated artists in Europe.”

In 1872 the firm was proud to offer the new Railroad Watch recently invented by the American Watch Co. of Waltham, Massachusetts. “Travelers by Railroad frequently find their Watches completely demoralized by the continuous jar of the train. To overcome this difficulty has long been a problem with watchmakers, and it is now successfully accomplished,” boasted an advertisement in Appleton’s Journal. “It is carefully adjusted, and may be entirely relied on to run accurately, wear well, and endure the hardest usage, without any derangement whatever.”

Certainly the promise of an end to demoralized or deranged watches must have been welcome news to 19th century travelers.

As the jewelry district followed its patrons northward, Ball, Black & Co. relocated in 1874.

|

| Fluted columns, both square and round, are crowned with exquisitely carved capitals -- photo by Alice Lum |

By 1890 the white marble palazzo was home to Banner Brothers, wholesale clothing merchants. Banner Brothers manufactured and sold “medium and better grades” of men’s apparel, doing about $1 to $1.25 million a year; a sum amounting to about $23 million today. Two years later the firm came under scrutiny by a United States Congressional committee looking into “the sweating system.” Decades before the miserable sweat shops that would force inhuman conditions on sewing girls, impoverished immigrant women and children would do “piecework” in their crowded tenement rooms. The committee was less interested in the fact that the conditions were poor, but that the “wages and prices in such manufacturers, as compared with the usual prices paid for like work not made in tenement houses on like clothing.”

When Herman S. Mendelson was called to testify on behalf of the firm, he was asked “Did you ever look up any of the places where your work was actually done to see the conditions under which it was done?” he answered, “No.”

To the follow-up question “Do you not consider it material to get the facts in such as case?” Mendelson replied, “It has never, within my knowledge, been known that any disease was brought about through the handling of manufactured goods in the city of New York in this way.” Within the year Banner Brothers was no longer at 565 Broadway.

Charles and Moritz Freedman purchased the building in 1893. The area, by now, was quickly becoming the center of the dry goods industry. Manufacturers and merchants of women’s wear, they envisioned an enlargement of the small sixth floor—creating a full story now visible from street level. Instead, however, they hired architects Little & O’Connor to raise the building four full floors.

The architects worked in light-colored brick, mirroring the corner quoins and the window pediments of the original structure. The resulting $50,000 addition was hardly noticeable to the casual passerby.

|

| Signs on the Freedman Brothers' enlarged building advertised "Cloaks & Suits" in 1895 -- King's Photographic Views of New York |

While the Freeman brothers ran their garment business here, they leased space to other firms. In 1899 Fred Kaufman, wholesale jewelers, moved from 41 Maiden Lane and would stay for a decade. In 1900 Herzig, Kipp & Co., manufacturers of silk undershirts was here.

That same year the Freeman brothers went bankrupt. Additional dry goods firms like Abrahamson Brothers, whose headquarters was in Oakland, California, and Hollins Manufacturing Company moved in.

In 1904 the street level was taken over by the Mechanics’ & Traders’ Bank as its Prince Street Branch. Apparel manufacturers continued to fill the upper floors. In 1912 Premier Notion Company was here selling collar stays; but the vast majority of tenants were women’s straw hat manufacturers. Among these were H. F. Sawyer & Co., Williamson & Sleeper, and R. Cinelli Hat Company.

|

| By 1905 the bank was now the Metropolitan Bank. Signs are plastered up the corner of the building and along its facade. -- photo NYPL Collection |

Weber and Heilbroner, “clothiers, haberdashers and hatters,” was here in 1920, as was Julius Mayer who dealt in “raw silk and thrown silk.” Weber and Heilbroner advertised “Knickerbocker suits for the skating wear of a well-groomed New Yorker. Coat, waistcoat and knickers—or coat, waistcoat, knickers and extra long trousers—for skating in winter and the links in summer.”

The bank on the first floor, now known as Metropolitan National, merged with Chase National Bank on November 22, 1921. Chase continued to refer to the location as the Prince Street Branch.

Soho suffered a severe decline during the middle of the 20th century and buildings were neglected and abused. No. 565 Broadway lost its cornice, but otherwise remained essentially unaltered despite its deteriorating marble. Then in the 1970s and 80s a renaissance occurred as artists discovered the cheap loft space with ample sunlight.

Galleries filled the side streets and avenues and artist studios took over former manufacturing or warehouse space. In 1979 Martin R. Fine commissioned restoration architect Joseph Pell Lombardi to converted 565 Broadway to residential cooperative apartments. Schulte Galleries leased the ground floor.

In 1992 the lost cornice was reproduced, the same year that two floors of the building were leased as the set of the reality television show “Home of the Real World New York.”

Today, the ground floor of 565 Broadway is home to a Victoria’s Secret store. Where women in voluminous hoop skirts once browsed among diamonds and silver coffee services, lacy bras and sheer negligees are displayed--a situation that might cause many a Victorian shopper to faint.

.png)