|

| The Era Magazine, July 1904, (copyright expired) |

Bond Street, stretching from Broadway to the Bowery, became perhaps the most exclusive address in Manhattan in the 1820s and 30s. As historian Sturges S. Dunham explained nearly a century later, in 1917, "Bond Street was one of the best known streets in the city and none stood higher in favor as a place of residence."

No. 31 Bond Street was built in 1827. The 26-foot wide mansion was faced in red brick and trimmed in marble. Three stories tall above a rusticated basement, it boasted handsome carved lentils, an arched double-doored entrance with a Gibbs surround, and wrought iron stoop newels which perched on paneled marble pedestals.

It became home to wealthy builder Timothy Woodruff within the year; however his stay here was short. He moved to No. 29 First Street in 1829. Mary Sutherland, the widow of Dr. Talmadge Sutherland, moved in and remained for a decade. The next resident, William Waring, also stayed for about ten years.

By 1850 changes were occurring on Bond Street. While still mostly upscale, many of its wealthiest residents were moving northward to Murray Hill and Fifth Avenue. Within the decade Bond Street would have the greatest concentration of dentist offices in the city. The New York Times described No. 31 Bond Street saying "It is of brick, with marble stoop, four stories high, and differs not materially from the rest of the buildings on the same block, all of which are several years old, and were in their day first-class and fashionable, now simply genteel."

|

| Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, February 1857 (copyright expired) |

In 1851 dentist Dr. John Lovejoy occupied No. 31 Bond Street. Then, on May 23, 1853 an advertisement appeared in The New York Herald announced "A. T. Smith, late with Dr. C. S. Rowell, begs to inform his friends and the public that his office is at No. 31 Bond street, where he will continue the practice of dentistry in all its various branches."

Dr. Smith performed his dental office downstairs--touting "artificial teeth inserted, from one to a full set, on the most approved principles, in a superior style, and on the most reasonable terms"--while the upper floors were operated as an upscale boarding house.

An advertisement in The New York Herald on April 26, 1854 offered "a very desirable location, where can be obtained a few elegant parlors and bedrooms, furnished or unfurnished, with partial board or without board...with hot and cold water on each floor, gas, bath, and all the modern improvements; they will be let to gentlemen who are willing to pay a fair price in advance. None others need apply."

Like Dr. Lovejoy before him, Dr. A. T. Smith was here briefly. In June 1855 he moved his practice to No. 306 Fourth Street, and the house was sold to another dentist, Dr. Harvey Burdell. It was valued at $30,000 at the time; about $850,000 in 2016.

Burdell was born near Herkimer, New York in 1812. By now he was well-established and wealthy (he also owned the house at No. 2 Bond Street). But neither his successful career or his wealth could overshadow his unpleasant character.

Writing in The Era Magazine in 1905, Will M. Clemens said of him "He was quarrelsome, penurious, greedy of appetite and fond of the company of women. He was often sued by women, and frequently appeared in one court or another. He was eccentric. He disliked men, but was very fond of guinea pigs."

Twice Burdell had been engaged to be married; and twice his repellent personality capsized the plans. In 1835 his engagement to a wealthy heiress was broken after he planted his fist in her father's eye. He later was to be married to the daughter of a rich businessman. But, as described by Clemens, "On the day set for the wedding, and in the presence of the clergyman and guests, Dr. Burdell flew into a passion because the father of the girl would not give to him before the ceremony a check for $20,000. The wedding was off. The girl married Burdell's groomsman and the latter then pocketed the $20,000 check."

|

| Dr. Harvey Burell. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, February 1857 (copyright expired) |

Burdell moved into No. 31 Bond Street, established his practice there, and like Smith, rented rooms on the upper floors. It was no doubt his excoriating demeanor which lead to the rapid procession of women who ran the boarding house--Mrs. Conway, then Mrs. Brulin, and Mrs. Jones who operated it in the early part of 1856.

Several of those rooms were occupied by Burdell's acquaintances (he was reportedly of "few friends" but had "a large acquaintance among persons of questionable character).

Despite his disposition, Dr. Burdell was a prominent member of the New York Historical Society and a director in the Artisan's Bank. Described as "a fine looking man, well proportioned, and of singularly youthful appearance," he owned country properties in New Jersey and Herkimer County, New York, and was the author of several books on dentistry.

Around the time that Burdell took over No. 31 Bond Street, he hired Mrs. Emma Augusta Cunningham as his housekeeper. She was the widow of a wealthy Brooklyn distiller and had two adult daughters, Margaret Augusta and Helen. The dentist and the housekeeper were equally matched, in terms of temperament. They quarreled and he fired her; but she and her daughters came back in 1855. It was a fatal decision on the doctor's part.

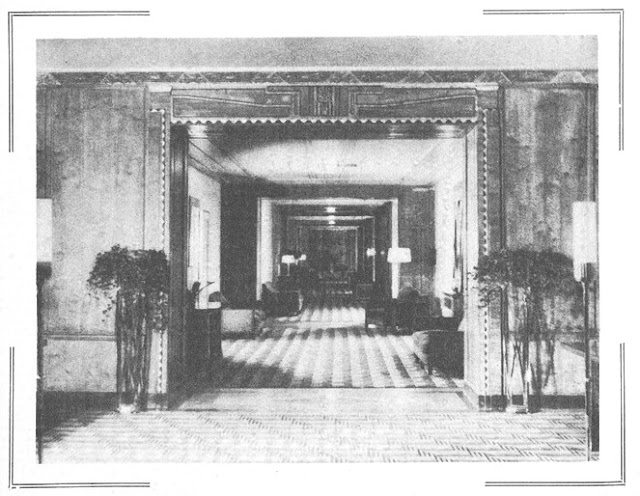

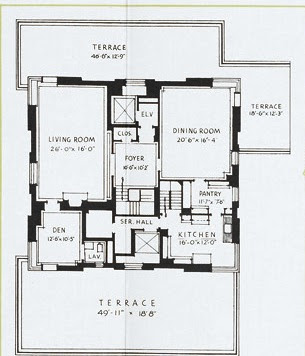

Will M. Clemens wrote "The front and back parlors on the first floor were used as reception rooms and were richly furnished. On the second floor the front room was occupied by Dr. Burdell as his sleeping apartment and the rear room was his dental office and operating room, it measured fifteen by twenty feet." In May 1856, after Mrs. Jones left, Emma operated the boarding house upstairs.

One of the residents of No. 31 Bond Street was John J. Eckel. Described as "a big man, physically, preferring the society of women and fond of food," he, like Burdell, had a bad temper. He was the lover of Emma Cunningham and had previously resided with her in various places.

Another roomer was George Vail Snodgrass, 18 years old. He too, professed his love for Mrs. Cunningham. Clemens remarked "She petted him and kept him always about her." Other boarders included Daniel Ullman, a lawyer; and Hannah Conlan, a cook.

The first signs of serious trouble came in December 1856 when Burdell ordered Emma to "vacate the house with her train." The two argued, and a few days later the dentist walked a potential new proprietor for the boarding house through the premises. This was one battle that Dr. Harvey Burdell would not win.

On March 2, 1857 The New York Times ran the headlines "Dr. Harvey Burdell Assassinated in his own Office in Bond-Street. Frightful Mutilation of The Body." At 8:30 on the morning of Saturday, February 28, Burdell's errand boy had arrived as usual. He found the dentist on the floor, "shockingly mutilated," in a pool of blood. The doors and walls of the room were blood-splattered.

Dr. John W. Frances, who lived nearby, was summoned. "He found that Dr. Burdell had been strangled by a ligature applied around the throat, and that no less than fifteen deep wounds, almost any of which would cause death, had been afflicted with some sharp instrument on his person."

|

| A quickly sketched crime scene map showed the position of the "dead body." The Era Magazine, July 1904, (copyright expired) |

The grisly details of the condition of the body and the crime scene were reported in gruesome detail in the daily papers. Police Captain Francis Speight described the scene as "a veritable slaughter-house." On February 2 The New York Herald wrote "The Bond street tragedy continues to be the all-absorbing topic of conversation. The shocking death of Dr. Burdell was spoken of in every circle." The article noted that both Snodgrass and Eckel were being held at the 15th Ward Station House, "although it does not yet appear that they know anything concerning the dreadful tragedy."

Bond Street was thronged with about 2,000 curiosity seekers on the morning of the funeral, March 5, 1857. The Times reported "Among these were individuals of all degrees of society. The rowdy, of course, was there; everybody who was idle was there; but there were other who never attend any demonstration of a kindred nature unless something very extraordinary or exceedingly peculiar characterizes the incident."

|

| Harper's published a rather gruesome etching of the dead dentist in February 1857. (copyright expired) |

Following the Grace Church services, the body was taken to Brooklyn's Greenwood Cemetery, where reporters were treated to a bizarre incident. A woman named Williams, who said she was a relative of Dr. Burdell, entered the reporters' carriage and stated that she had chosen the burial plot herself. She lashed out at Emma Cunningham, saying loudly "The doctor's sentiments towards Mrs. Cunningham were well known to his friends--that he always expressed the utmost aversion to her, and, to use his own words, would rather be torn in pieces with hot pincers than marry her."

She then reported that the dentist had made a will about a year earlier and that she thought "it probable that the same will had been either stolen or altered." Her protests were in reaction to Emma Cunningham's testimony at the coroner's inquest that on October 25, 1856 she and Burdell had been secretly married.

|

| Emma Augusta Cunningham Harper's Weekly, May 9, 1857 (copyright expired) |

The Era Magazine later wrote "Scandal and gossip dwelt on the story that Dr. Burdell's landlady, the buxom Mrs. Cunningham, had sustained the relation of mistress to him, that she claimed to have been secretly married to him, that she was unscrupulous and strong-minded enough to engage in an intrigue against his fortune if not his person, and that the house, though respectable and aristocratic externally, was within the scene of continual bickerings, hostilities, jealousies and schemes--of espionage through keyholes, of larcenies of papers, of suspicions among servants, of quarrels in the entries and indecorums in the chambers."

Later testimony by The Rev. Mr. Marvine, who performed the Burdell-Cunningham marriage, drew more suspicion than conclusion. He was unable to identify either Burdell (whose body he had viewed) nor Emma Cunningham as the two he had married. But he was certain that Emma's daughter, Augusta, had been one of the witnesses. He added "that as the party left the house the supposed Mrs. Burdell requested that no publication be made of the marriage."

|

| On the first day of Emma Cunningham's trial the courtroom was standing-room only. Harper's Weekly, May 9, 1857 (copyright expired) |

Other witnesses agreed that Burdell had claimed "a fear of assassination." Emma Cunningham and John Eckel were arrested and tried for murder. Prosecutors could provide no direct evidence, however, and Emma had an alibi. Both daughters testified that they slept with her on the night of the murder. The verdict read on February 15, 1857 was "not guilty." (The Times later complained that the verdict should have been "Not Proven" rather than "Not Guilty.")

The courts set about liquidating Burdell's properties. On March 30 a public auction of the furnishings and dental equipment was held in the house. The New York Herald noted that for weeks "a crowd stood gaping at the premises No. 31 Bond street, anxiously desiring to get a view of the interior of the house in which such a strange and fiend-like tragedy had been enacted."

The stream of people who filed through the house were less interested in the items offered than in ghoulish curiosity. "The back room on the second floor, the walls and doors of which are still besplattered with the blood of the deceased, was the central point of attraction," noted the Herald.

The newspaper dared to say what went through the minds of many. Mentioning that the Cunningham daughters were in the house, it wrote "Who can say during the hours the live throng was so actively engaged beneath them, what thoughts may have filled their breasts, what relenting, what forebodings may have burdened their hearts, if guilty of connivance at the murder?"

The items auctioned off reflected the wealth of the murdered dentist. Oil paintings, velvet carpets, mahogany furniture, and chandeliers were sold.

But newspaper readers had not heard the last of Emma Cunningham. She had begun laying claim to Burdell's $100,000 estate even while in prison. She summoned Dr. David Uhl to her cell, saying she had symptoms of pregnancy. Then on Monday night, August 5, 1897, an unknown man called on Dr. Uhl to come to the rooms where Emma was staying.

Another doctor was already there and the room was darkened. Emma was contorting under bloody sheets, "and in due time, after considerable groaning and moaning, the expectant heir was brought forth," reported the New-York Daily Tribune. "Dr. Uhl left the house and the case to the charge of others, who were on hand at the door."

On September 15 The New York Times reported "The fictitious baby at Barnum's did not prove attractive yesterday...and people also began to think, as one lady visitor remarked, that there was no difference between Mrs. Cunningham's bogus baby and other babies."

The comment was spurred by the recent revelation that Emma Cunningham had "borrowed" the infant from an orphanage operated by the Sisters of Charity, and the attending doctor who "delivered" the child was an accomplice. Testimony revealed he had doused the bed with a pail of blood before Dr. Uhl's arrival. Emma, her cohort and her two daughters were arrested in what the New-York Daily Tribune called "a plot so audacious and so deliberately carried out that it looks more like the romantic invention of a novel writer than the sober reality of actual experience."

While the astonishing story played out, Dr. Burdell's brother, also a dentist, had moved his practice into the Bond Street house. Dr. Lewis Burdell shared the the office space with a Dr. Wilson. Just as public attention to No. 31 was waning, fire broke out at around 12:30 on the afternoon of April 20, 1858. Although the blaze, which originated in a defective kitchen range, was quickly extinguished and little damaged was sustained, the New-York Daily Tribune noted that it was "the cause of no little excitement in the neighborhood."

In January 1861 Lewis Burdell sold the house for $17,050. Despite its tainted reputation, the new owner continued operating a boarding house here, advertising "a large parlor, suitable for a gentleman and wife" on May 1, 1866.

But public attention returned to the address on October 6, 1869 when The New York Herald ran the headline "ANOTHER BOND STREET HORROR--A Man Found Dead in the Burdell-Cunningham House."

John B. Felton, a distillery worker, had boarded in the house for some time. On Sunday evening, October 3, he had gone to his room in the rear of the building. The Herald reported "Nothing strange, however, was thought of the matter till yesterday morning, when a very oppressive odor throughout the house was detected, and an examination showed that it proceeded from Felton's room."

Although doctors were unable to ascertain the cause of death immediately, the mysterious death in the murder house was irresistible fodder for the press.

On August 25, 1888 A. Wolff of the banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb & Co. announced that he had commissioned architects De Lemos & Cordes to design a six-story store building at No. 31 Bond Street. It was the end of the line for the once-elegant mansion and one of the most notorious murder mysteries of the 19th century.

|

| The De Lemos & Cordes replacement structure survives, somewhat altered. Real Estate Record & Guide, May 10, 1890 (copyright expired) |

As for the players in that affair, the disgraced Emma Augustus Cunningham had gone to California. She returned to New York in 1884 and died penniless in Harlem on September 13, 1887. She was buried, ironically, in the same cemetery as Dr. Harvey Burdell. John J. Eckel died in 1869 in the Albany Penitentiary where he was serving a sentence for "whisky frauds;" and George died in Brooklyn in 1872. The sensational Burdell murder case was never solved.

.png)