|

| photo nyago.com |

In 1850 there were 4,531 Italian immigrants in the United States. Ten years later the number had more than doubled. With no Italian-speaking parish in New York City, Archbishop Hughes worried about the growing number of Italian Catholics who had no place to worship. An Italian priest was given the charge of establishing a small chapel on Canal Street dedicated to Saint Anthony of Padua.

Cardinal John McCloskey, in 1865, entreated the group of Franciscans who had settled in upstate New York to set up an Italian parish to replace the little chapel. Father Leo Pacillo responded, establishing the Italian national parish of St. Anthony of Padua in 1866. The parish used the former Free Congregational Church at 149-151 Sullivan Street near West Houston Street. Somewhat ironically, its first official act was the baptism on March 23, 1866 of an Irish baby, Elizabeth Kelly.

In 1882, the land adjacent to the church formerly occupied by a brewery was scheduled for auction. By now, the church structure was inadequate for the quickly increasing membership and the parish desperately needed the land in order to expand. On the day of the auction, January 31, the city was hit with a major blizzard. Father Anacletus DeAngelis was the only bidder who made it to the auction through the storm.

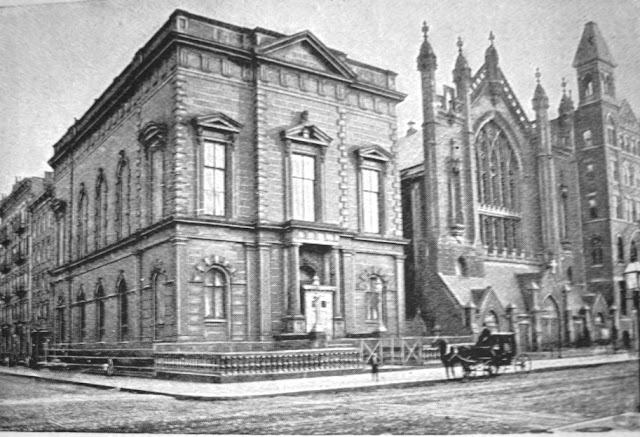

English-born Arthur Crook, who would design several Manhattan churches, was selected as the architect. The Italian congregation asked for a structure of which they could be proud–one on a par with the Old Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. Crook created a granite faced Romanesque building reminiscent of churches the Italians remembered from their homeland. It would be the first church constructed by an Italian community in the United States.

On June 14, 1886, Archbishop Michael Corrigan presided over the laying of the cornerstone. Inside was a tin box holding newspapers and several gold and silver coins.

As the church slowly took shape, marble artisans in Carrara, Italy were at work on the altar, communion rails and pulpit. The marble work alone would cost $12,000. The contract for the stained glass windows was finalized, costing $10,000, and a 2,400-pipe organ was being built by George Jardine & Son at a cost of $8,000.

At last, on June 10, 1888, the church was dedicated. Stretching back 150 feet, it was 75 feet wide and rose 100 feet at its highest point. Above the central of the three entrances stood a life-size figure of Saint Anthony. Dominating the main façade was a 26-foot diameter rose window. Behind the church and connected to the monastery that fronted Thompson Street was a campanile housing three large bells. The largest, weighing 5,000 pounds, was dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua; the second, weighing 3,000 pounds, to “Blessed Virgin Conceived Without Sin,” and the smallest at 1,500 pounds was dedicated to St. Francis of Assisi.

Inside the space soared upward to 86 feet. There were 33 stained glass windows–14 in the clerestory, 14 along the side aisles and five in the sanctuary. Fifteen hundred worshippers could be accommodated. The total cost of the church and monastery was $200,000. Tall cast iron columns with gilded capitals were painted to simulate veined marble. According to The New York Times, “Boldness of outline and perfection of proportion have been relied on rather than gaudy decoration.”

Cardinal John McCloskey, in 1865, entreated the group of Franciscans who had settled in upstate New York to set up an Italian parish to replace the little chapel. Father Leo Pacillo responded, establishing the Italian national parish of St. Anthony of Padua in 1866. The parish used the former Free Congregational Church at 149-151 Sullivan Street near West Houston Street. Somewhat ironically, its first official act was the baptism on March 23, 1866 of an Irish baby, Elizabeth Kelly.

In 1882, the land adjacent to the church formerly occupied by a brewery was scheduled for auction. By now, the church structure was inadequate for the quickly increasing membership and the parish desperately needed the land in order to expand. On the day of the auction, January 31, the city was hit with a major blizzard. Father Anacletus DeAngelis was the only bidder who made it to the auction through the storm.

English-born Arthur Crook, who would design several Manhattan churches, was selected as the architect. The Italian congregation asked for a structure of which they could be proud–one on a par with the Old Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. Crook created a granite faced Romanesque building reminiscent of churches the Italians remembered from their homeland. It would be the first church constructed by an Italian community in the United States.

On June 14, 1886, Archbishop Michael Corrigan presided over the laying of the cornerstone. Inside was a tin box holding newspapers and several gold and silver coins.

As the church slowly took shape, marble artisans in Carrara, Italy were at work on the altar, communion rails and pulpit. The marble work alone would cost $12,000. The contract for the stained glass windows was finalized, costing $10,000, and a 2,400-pipe organ was being built by George Jardine & Son at a cost of $8,000.

At last, on June 10, 1888, the church was dedicated. Stretching back 150 feet, it was 75 feet wide and rose 100 feet at its highest point. Above the central of the three entrances stood a life-size figure of Saint Anthony. Dominating the main façade was a 26-foot diameter rose window. Behind the church and connected to the monastery that fronted Thompson Street was a campanile housing three large bells. The largest, weighing 5,000 pounds, was dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua; the second, weighing 3,000 pounds, to “Blessed Virgin Conceived Without Sin,” and the smallest at 1,500 pounds was dedicated to St. Francis of Assisi.

Inside the space soared upward to 86 feet. There were 33 stained glass windows–14 in the clerestory, 14 along the side aisles and five in the sanctuary. Fifteen hundred worshippers could be accommodated. The total cost of the church and monastery was $200,000. Tall cast iron columns with gilded capitals were painted to simulate veined marble. According to The New York Times, “Boldness of outline and perfection of proportion have been relied on rather than gaudy decoration.”

|

| The life-size status of St. Anthony stands beneath the 26-foot rose window -- photo by Michelle Rick |

Throughout the coming decades the parish would be known for its colorful Feast of Saint Anthony. Although the feast started out rather solemnly, it evolved into a carefree, week-long street fest of Italian food.

In 1905, The New York Times reported on the feast:

In 1905, The New York Times reported on the feast:

Little Italy’s dark, dismal streets, with their towering tenements, many of which shelter thirty families of astonishing size, were transformed yesterday into a riot of color and gayety in honor of the feast of St. Anthony of Padua. All work was abandoned, men, women, and children donned their holiday attire, and everybody kept open house for visitors, who came from all parts of the city and State to participate.

The newspaper described the “pinwheel and paper flower men,” the organ grinder with his pet monkey, and musicians in colorful uniforms. But most evident was the array of food. The article described, “fancifully molded cheeses made of goats’ milk. Piles of tomatoes and cucumbers were on the pushcarts. They were bought and eaten as they were, and it was no uncommon sight to see an Italian child just able to toddle about gnawing away at a big green cucumber with apparent delight and relish.”

In April 1914, two young women from St. Louis sent a small box of gold trinkets to the church, “expressing the hope that they might be devoted to the honor of St. Anthony.” The following Sunday the gift was announced from the pulpit. Congregants soon began showering the church with jewelry and precious metal items.

“Within two weeks we had 200 gifts,” remarked Father Silvione, “and in another month 500 had made donations. They were mostly gold rings, and some came from all parts of the East.”

By June, the priest had had a gold reliquary, studded with gems, fashioned from the donated jewelry, which was put on view during the Feast of St. Anthony that month.

|

| The church in 1930 as Houston Street is being widened -- photo NYPL Collection |

Tragedy occurred on November 4, 1938. That morning the monastery caught fire and quickly spread. One young lay brother, here only one year from Italy, perished along with a cook. Priests were trapped, some jumping out windows to adjoining buildings or clinging to window ledges praying for help. Seven priests were saved by firefighters.

Father Fagan proved to be a true hero. He had escaped, but rushed back into the blazing building to rescue Father Louis Vitale. He returned yet again to rescue Father Bonaventure Pons. With flames surrounding him, Father Fagan jumped from a window to a roof below. He died of his burns five days later.

The Church of St. Anthony of Padua is still run by the Franciscan brothers and while its congregation is more ethnically mixed, the annual Feast of Saint Anthony goes on, memorialized in the an unforgettable scene in the movie The Godfather.

Father Fagan proved to be a true hero. He had escaped, but rushed back into the blazing building to rescue Father Louis Vitale. He returned yet again to rescue Father Bonaventure Pons. With flames surrounding him, Father Fagan jumped from a window to a roof below. He died of his burns five days later.

The Church of St. Anthony of Padua is still run by the Franciscan brothers and while its congregation is more ethnically mixed, the annual Feast of Saint Anthony goes on, memorialized in the an unforgettable scene in the movie The Godfather.

.png)