|

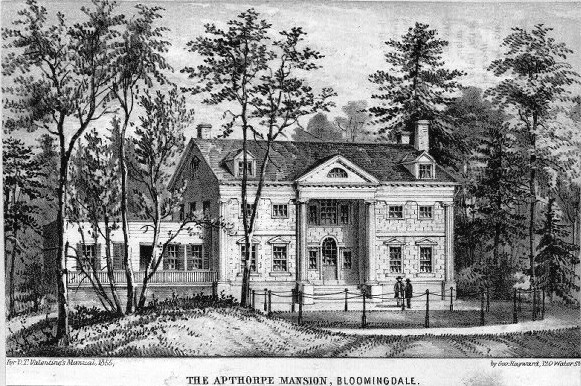

| print NYPL Collection |

Thomas Osborne was the Irish-born owner of a successful stone-cutting business on the east side of Manhattan. With a nearly-unlimited supply of stone at cost, construction of a stone-clad apartment building made perfect sense.

For $210,000, Osborne purchased from restauranteur John Taylor the large lot of land at 57th Street and Seventh Avenue. In 1883, the neighborhood still consisted of small commercial buildings and stables. The concept of upper-class apartment buildings was in its infancy and Osborne knew he had to pull out all the stops to make his project attractive to wealthy residents.

James E. Ware was commissioned to design the building that Osborne would name after himself. He was given the task of producing a building that would attract affluent New Yorkers accustomed to large, refined houses. Apartment buildings were still associated with the lower classes.

Ware's imposing, fortress-like structure was a blend of Italian-Renaissance, Romanesque and Renaissance styles. Originally 11 stories on 57th Street and 14 stories to the rear (although, because the front apartments had 15-foot ceilings, the 57th Street elevation was taller),the structure was wrapped by three balustraded cornices at the third, seventh and tenth floors. A deep, arched porch framed the entrance and bay windows from the third through sixth floors added dimension and interest to the façade.

Lobby clock amid encrusted decoration -- Photo columbia.edu

It was on the interiors, however, that Ware lavished his attention. It was essential that the lobby impress even the most jaded New Yorker. Working with Tiffany Studios, artists J. A. Holzer, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and John LaFarge fashioned created a sumptuous common space of mosaics, multi-colored marble, gold leafed details and murals. Under a coffered ceiling, carved stone niche benches sat upon mosaic and inlaid marble floors.

Visitor's waiting bench -- photograph columbia.edu

Osborne’s original intention was to sell the building rather than to run it, and as construction continued he attempted to do so. There were no buyers, however, and the project went forth.

|

| photograph via columbia.edu |

To ensure up-to-the-minute amenities, the building was outfitted with four Otis elevators, steam heat, modern plumbing, and electricity. To lessen the chance of fire, staircases were constructed of iron and marble. The apartments, some of which were duplexes, had parquet floors, Tiffany windows, oak and mahogany woodwork, tiled fireplaces and built-in cabinetry. Some apartments had bronze mantelpieces and crystal chandeliers. Secret passageways slipped domestics unseen from the front door to the kitchen.

And to keep the tenants fit, an all-weather croquet ground was installed on the roof to permit year-round exercise. For residents’ convenience, the basement level was to house a florist, doctor and pharmacy.

The Osborne Flats was completed in 1885, two years after ground breaking. The $1,209,00 cost drove Osborn into bankruptcy and, ironically, the building was sold to John Taylor who had originally owned the land. Taylor’s estate lost the building to foreclosure in 1888 when it was purchased by William Taylor, another relative, for $1,009,250 -- $200,000 less than the cost of construction.

In 1889, Ware was called back to add another story to the rear, leveling the roofline. Only seven years later, the demand for more space in The Osborne necessitated architect Alfred S. G. Taylor to add a 25-foot extension to the west side. Taylor (also a relative of John Taylor and a part-owner of the building) was sympathetic to the original Ware designs so that his addition is nearly unnoticeable.

And to keep the tenants fit, an all-weather croquet ground was installed on the roof to permit year-round exercise. For residents’ convenience, the basement level was to house a florist, doctor and pharmacy.

The Osborne Flats was completed in 1885, two years after ground breaking. The $1,209,00 cost drove Osborn into bankruptcy and, ironically, the building was sold to John Taylor who had originally owned the land. Taylor’s estate lost the building to foreclosure in 1888 when it was purchased by William Taylor, another relative, for $1,009,250 -- $200,000 less than the cost of construction.

In 1889, Ware was called back to add another story to the rear, leveling the roofline. Only seven years later, the demand for more space in The Osborne necessitated architect Alfred S. G. Taylor to add a 25-foot extension to the west side. Taylor (also a relative of John Taylor and a part-owner of the building) was sympathetic to the original Ware designs so that his addition is nearly unnoticeable.

|

| The Osborne Flats 1915 - NYPL Collection |

Modernization came in 1919 when the light moat around the basement was filled in, the handsome entrance porch was removed, and the balustrades stripped from the cornices.

Despite the financial problems, Thomas Osborne’s vision of a residence for the elite had came true. Throughout its history, The Osborne housed both the rich and famous. United States Senator John Coit Spooner was an early resident and Philip T. Dodge was living here in 1928 when he married Lilian Sutherland, 20 years his junior. Entertainers Vera Miles, Imogene Coca, Lynn Redgrave, Clifton Webb, humorist Fran Lebowitz, Andre Watts and fashion designer Fernando Sanchez all called The Osborne home.

As a strange historical footnote, The Euthanasia Society of America held its meetings there in the home of Mrs. Joseph M. Proskauer, a director of the society in the 1950s.

In 1961, the Taylor family sold The Osborne to a developer with plans to replace the building with a high rise apartment building. The residents revolted. Forming a cooperative, they save the building by purchasing it for $2.5 million. Commenting on the rescue, The New York Times said. “Where else but at the Osborne apartment house could you open one closet and hear Blanche Thebom vocalizing and another and listen to Van Cliburn practicing?”

That year, Leonard Bernstein purchased apartment 4B, later to be sold to actor Larry Storch, who sold it to entertainer Bobby Short in 1970. Tragedy struck when, on October 19, 1978, police arrived at the apartment of actor Gig Young. Young had shot to death his wife of three weeks, Kim Schmidt, then turned the gun on himself.

In 1988, Robert Osborne, the host of Turner Classic Movies was looking for an apartment in Manhattan. Carol Burnett told him of an apartment in the Osborne being sold by a friend. Osborne toured with apartment with actress Bette Davis before purchased it–the first of his three apartments he owned there.

Throughout the 20th century about half of the apartments were divided into smaller spaces; however many of them retain their original grandeur. Referred to by the AIA Guide to New York City as “The dour matriarch of 57th Street,” The Osborne was granted landmark individual status in 1991.

Despite the financial problems, Thomas Osborne’s vision of a residence for the elite had came true. Throughout its history, The Osborne housed both the rich and famous. United States Senator John Coit Spooner was an early resident and Philip T. Dodge was living here in 1928 when he married Lilian Sutherland, 20 years his junior. Entertainers Vera Miles, Imogene Coca, Lynn Redgrave, Clifton Webb, humorist Fran Lebowitz, Andre Watts and fashion designer Fernando Sanchez all called The Osborne home.

As a strange historical footnote, The Euthanasia Society of America held its meetings there in the home of Mrs. Joseph M. Proskauer, a director of the society in the 1950s.

In 1961, the Taylor family sold The Osborne to a developer with plans to replace the building with a high rise apartment building. The residents revolted. Forming a cooperative, they save the building by purchasing it for $2.5 million. Commenting on the rescue, The New York Times said. “Where else but at the Osborne apartment house could you open one closet and hear Blanche Thebom vocalizing and another and listen to Van Cliburn practicing?”

That year, Leonard Bernstein purchased apartment 4B, later to be sold to actor Larry Storch, who sold it to entertainer Bobby Short in 1970. Tragedy struck when, on October 19, 1978, police arrived at the apartment of actor Gig Young. Young had shot to death his wife of three weeks, Kim Schmidt, then turned the gun on himself.

In 1988, Robert Osborne, the host of Turner Classic Movies was looking for an apartment in Manhattan. Carol Burnett told him of an apartment in the Osborne being sold by a friend. Osborne toured with apartment with actress Bette Davis before purchased it–the first of his three apartments he owned there.

Throughout the 20th century about half of the apartments were divided into smaller spaces; however many of them retain their original grandeur. Referred to by the AIA Guide to New York City as “The dour matriarch of 57th Street,” The Osborne was granted landmark individual status in 1991.

.png)