|

| print NYPL Collection |

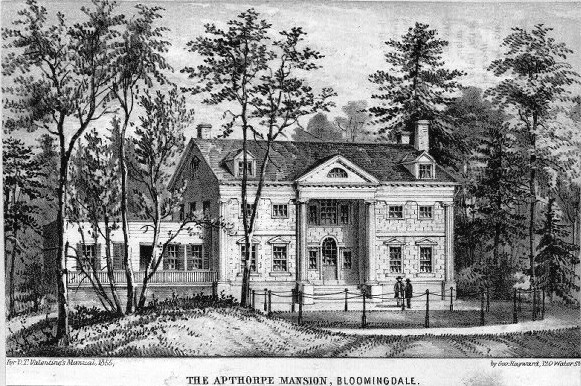

In the 18th century, the area north of the established city of New York that is now the Upper West Side was a bucolic, rural area called Bloomingdale. Landed gentry farmed large estates and built magnificent country seats.

In 1762 Charles Ward Apthorp purchased 115 acres from Dennis Hicks and, a year later, another 153 adjoining acres from Oliver de Lancey. In all he spent about $15,000 for both properties. In 1764 his grand mansion--in keeping with his social status--was completed.

Apthorp was an important figure in those pre-Revolutionary years. A loyal British subject and successful merchant, he was a member of the Governor’s Council from 1763 through 1783 when the war ended.

Apthorp’s house was among the grandest on the island. Named Elmwood, it sat on a rise from which the Hudson River and the palisades on the opposite shore were visible. The wooden structure was covered with gray stucco to simulate stone. A deeply recessed entranceway that sheltered a handsome arched doorway was supported by fluted Ionic pillars, surmounted by a classic pediment. Over the doorway was a fashionable Palladian window. The east and west facades were identical.

The doorways opened onto a spacious entrance hall. Three large rooms made up the ground floor, the most impressive being the mahogany paneled dining room. In keeping with Apthorp’s allegiance, the carved mahogany mantelpiece included the head of a crowned king.

A broad, winding staircase lead to the second floor which housed three more rooms, two of which would serve as bedrooms for the ten children. Above, the roomy dormered attic had nine rooms, “doubtless affording in former days ample accommodation for numerous domestics and poor relations,” according to The New York Times a century later.

Sitting at what is now 90th and 91st Street and Columbus Avenue, the house was accessed by a 40-foot lane to the Bloomingdale Road (now Broadway) and another to the Post Road (now Fifth Avenue). As shortcuts to the neighboring estates, Apthorpe laid out other roads across his property, such as Striker’s Lane and Jauncey’s Lane. The innocent-sounding thoroughfares would later prove problematic.

|

| print from the NYPL Collection |

Apthorp’s idyllic country life was shattered with the outbreak of revolution. After the disastrous Battle of Long Island, General George Washington fled north to regroup, taking over the mansion as his headquarters. As soon as Aaron Burr, Israel Putnam, and the other American officers had moved their soldiers to Bloomingdale, Washington moved on.

Within hours the British General Howe arrived, taking the mansion as his headquarters and remaining through the fighting of the Battle of Harlem Heights. Apthorp was one of the signers of the address given to General Howe on the occupation of the city and was given the sinecure appointment of second assistant manager of the Court of Police in 1777 with a salary of 200 pounds. Before the war’s end, Sir Henry Clinton and Lord Cornwallis had also taken over the mansion.

With the final defeat of the British, Apthorp was arrested and tried for high treason. For reasons not documented, however, he was released and permitted to keep his estate, although his sizable property in Massachusetts was confiscated.

On January 3, 1789 the mansion was the scene of the marriage of Apthorp’s daughter to Congressional Delegate Hugh Williamson. Maria Apthorp was described as “lovely and accomplished,” by the New York Daily Gazette.

After Charles Ward Apthorp died in 1797, Williamson bought out the other nine children at a forced sale to recover a $1,500 mortgage on the property. Problems started almost immediately, however, since Charles Apthorp’s will divided up the property using as boundary lines the small lanes across the property. Legal battles lasted over a century revolving around issues such as whether or not the property lines went to the curbs of the lanes, to the middle, or included the entire roadways. As the siblings married into other moneyed families such as William Waldorf Astor, Schuyler Hamilton, and Paul Livingson Mottelay, those well-known names became entangled in the litigation as well. By 1910, when the lawsuits were finally settled, the Apthorp land was estimated to be worth approximately $125 million.

In the meantime, the once-grand mansion was being encroached upon by the developing city. As The New York Times commented on February 9, 1890, “The history of the Apthorpe [sic] mansion during the present century is one of neglect and gradual decay.”

As the city closed in, the residence became the centerpiece of a picnic ground known as Elm Park. One contemporary historian noted that “The once beautiful Apthorp mansion now houses a beer and dance saloon.”

The 69th Regiment used the grounds as their review and drill grounds in 1855, and in 1878 the 79th Highlanders, Old Guard, used the grounds for a picnic and sporting contests, including the shot put, 200-yards run, the light hammer throw, and the standing jump.

It was the afternoon of July 12, 1870, however, that people remembered. On that day 3,000 Irish Protestants were enjoying a picnic on the grounds of Elm Park. A mob of Irish Catholic laborers entered the park in what was to become known as the Orangeman Riots, killing five picnickers and gravely injuring hundreds.

Yet the house still retained its architectural dignity. Contemporary historian Mary Louise Booth wrote “Around this old mansion still linger the stateliness and beauty of its aspect in the past…The stately recessed portico, with its supporting Corinthian columns, the corresponding pilasters, and the high, arched door-way at the middle of the house opening into a spacious hall, give an aristocratic air quite superior in pleasantness of impression to any of the more pretentious of modern houses in the city.”

She added “It ought to be preserved as an interesting historical relic of the metropolis.”

Indeed, it should have been. However in 1891 the city announced that the Apthorp mansion would be razed for the extension of Ninth Avenue north.

The New York Times lamented the news saying “An old house is like an old citizen, in that it deserves an ‘obituary.’”

The Apthorpe Mansion shortly before demolition 1891 - NYPL Collection

A century before historic preservation was heard of, one of New York City’s most historic and architecturally important structures was ripped down for a strip of asphalt. The stately residence where Revolutionary War history was written is largely forgotten.

hugh willimson is in my family

ReplyDeleteRecords show the family name had no E at the end.

ReplyDelete