The brick fireback on the side, looking much like a bricked-up opening, prevented the heat of the fireplace from setting fire to the clapboards. from the collection of the New-York Historical Society

Wheaton Bradish arrived in America from Ireland in 1809. He and his family lived at 483 Bowery until 1838, after which they moved to 78 West 11th Street in Greenwich Village. Their two-and-a-half-story clapboard house was recently erected, West 11th Street having been opened in 1830. It sat next to the walled remnants of the 1805 Cemetery of Congregation Shearith Israel, at least half of which had been relocated when West 11th Street was created. To the west of the Bradish house was a frame, 18th century roadhouse, by now known as the Grapevine Tavern.

The builder of 78 West 11th Street was no doubt responsible for its vernacular design. Diminutive attic windows faced 11th Street, and a large brick chimney testified to the size of the fireplaces inside. Bradish and his wife Harriet had four daughters, Harriet, Emily, Catherine Trenor, and Eliza.

Although the wooden residence appears humble by a 21st century viewpoint, it was a substantial home to a successful merchant. Proud of his heritage, Bradish was first vice-president of the St. Patrick's Society, and had been a vice-president in the American-Irish Historical Society since around 1831.

In 1840, the family traveled to England. It was there, in Upper Heigham, that Harriet died at the age of 38 on October 29.

Bradish married Emily Proctor, a widow, a few years later. (It appears that she was the mother-in-law of Wheaton's daughter, Emily, who was married to John Proctor. If so, she was now both the younger Emily's step-mother and mother-in-law.)

Of the Bradish daughters, only Harriet would not wed. Eliza was married to Charles Stewart Smith, and Catherine Trenor married Henry Rudolph Kunhardt in 1857. (The Kunhardt's son, Wheaton Bradish Kunhardt, would become a noted engineer and author.)

Following the death of her husband, Emily Bradish Proctor moved back into the West 11th Street house. She died on October 4, 1851 and, somewhat surprisingly, her funeral was not held in the parlor, but at St. Mark's Church on East 10th Street.

The Bradish family left West 11th Street by 1856, when it was home to Charles T. Wetmore, another affluent businessman, and his wife.

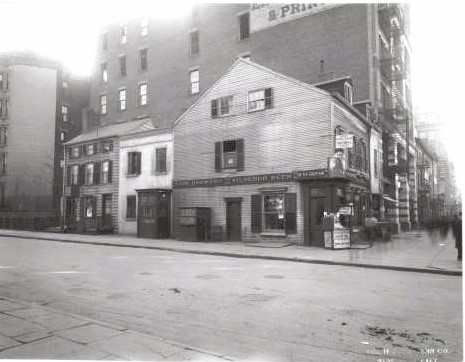

The former Bradish house displays a tailor's sign in the late 1890's. from the collection of the New York Public Library

In an interesting sidenote, on June 29, 1862, The New York Times reported that Wheaton Bradish had died "suddenly" two days earlier at the age of 76. The term often referred to a heart attack, but not in this case. The Annual Reports of the Railroad and Canal Companies of the State of New Jersey explained that for some unknown reason, Bradish was walking on the railroad tracks near Orange, New Jersey that day when he "was struck by the engine of a passenger train and killed."

The Wetmore's puppy went missing in 1857. Offering a $5 reward (about $175 in 2023), Wetmore gave a detailed description:

Strayed from 78 West Eleventh street, on the afternoon of Tuesday, Dec. 1, a young Skye terrier, color blueish gray, short tail and very short cut ears, hair long and wavy, seven or eight inches high. Answers to the name of Nelly.

Apparently the incident did not greatly increase the Wetmores' vigilance. Nelly was missing again in January 1859, and once again, a $5 reward was offered.

John C. Tillotson boarded with the Wetmore family from 1856 until 1862. Although he did not list a profession in city directories, it appears he dealt in real estate. In reporting on a fire that destroyed the boarding house at 136 Grand Street on November 16, 1860, The World noted, "The house was the property of J. C. Tillotson, residing at 78 West Eleventh street."

With Tillotson's rooms vacant, in May 1862 the Wetmores advertised, "Desirable Rooms for gentlemen," noting, "Breakfast and Tea in room, if desired." A later ad pointed out that the rooms were "in a private family, where there are no children."

In 1866 the Wetmores were absent for a year, possibly traveling in Europe. The fashionable tenor of the house and the block was evidenced in their ad on October 7, 1866: "To Rent--A nicely furnished house, 78 West Eleventh street, between Fifth and Sixth avenues. Rent $350 per month." The monthly cost would translate to about $6,650 today.

After occupying 78 West 11th Street for 16 years, the Wetmores left in April 1872. It was purchased by Henry Post Mitchell and his wife, the former Rebecca Simmons. Born in 1841 to a colonial Philadelphia family, Mitchell was a graduate of Yale University. His "oils" business had two locations, on First Avenue and on Pearl Street. The couple had five children.

Five years after moving in, the Mitchells left 78 West 11th Street and it became home to a colorful couple, Count Emile Leon de Brémont and his wife, Anna Elizabeth, Comtesse de Brémont. A former officer in the French Army and a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, De Brémont was a physician. Like many immigrants of noble birth, he dropped his title upon coming to America. The New York Herald noted that he was "well known and highly regarded among the French 'colony.'" Dr. De Brémont ran his medical practice from the house, and it was most likely he who added a second door, to be used by his patients.

The countess was born Anna Elizabeth Dunphy in New York around 1849, and grew up in Cincinnati. An accomplished vocalist, she returned to New York and was a contralto soloist in Henry Ward Beecher's Plymouth Church in Brooklyn. The couple were married in 1877.

On May 21, 1882, the New York Herald reported, "The Count Emile de Brémont, better known in this city as Dr. Leon le Brémont, died on Friday evening at his residence, No. 78 West Eleventh street of congestion of the lungs." The article noted, "his funeral on Tuesday will be attended by the Garde Lafayette."

Following her husband's death, Anna turned to the stage. The following year, The New York Mirror wrote, ""Mme. La Comtesse de Brémont, nee Dunphy, who has, after pluming her flight under a stage name with success last season, determined to try her fortune in the coming year. Mme. de Brémont is a tall, graceful young lady, with a very decided talent for acting, and a rich and mellow contralto voice, which she manages with skill."

Anna de Brémont's venture was a success. She moved to Europe, and in 1888 was initiated into the Order of the Golden Dawn. Along with her brilliant stage career, she was a successful author, writing among other works a memoir about Oscar Wilde and his mother.

In the 1890's, the former doctor's office at 78 West 11th Street was home to a tailoring business, and by the turn of the century John L. Dunlap lived and ran his business, the Local Credit Company, in the house. He also had an office downtown on Park Row.

On August 3, 1900, police officers entered the 11th Street office and arrested Dunlap for usury. The managers of a silk company, Scheffer, Schram & Vogel, had discovered that "a number of employees of the firm borrowed money from Dunlap some time ago," explained The New York Times, "and finally told their employers." Dunlap had loaned the factory workers, most of them immigrants who did not understand what they were signing, small amounts, which by the terms of the agreement they were never able to pay off. One borrower was Charles Witner, who borrowed $30 in June 1898. The complaint said in part:

He was charged $3 for notary services, $1 for investigating expenses, and $3 for the first month's expenses. As he was only paid every two weeks by his firm he paid Dunlap at the same time, giving him $15 each two weeks. He said that by the method of paying he renewed the loan once a month, and up to this time, according to receipts which he has, has paid Dunlap for $124 for the $30.

As the date of Dunlap's trial approached, a reporter from The Evening World interviewed locals. In his article on August 6, 1900, he quoted a Sixth Avenue businessman who said, "That fellow Dunlap has hundreds of poor employees in this neighborhood tied up. Once in his clutches it is hard to get out of them."

Dunlap was found guilty of usury, but apparently was fined rather than jailed. He continued running his business from 78 West 11th Street for years.

Then, in 1915, the quaint wooden house, a relic of a much different Greenwich Village, was demolished along with its venerable neighbor on the corner to make way for a modern apartment house.

many thanks to historian Anthony Bellov for suggesting this post.

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.jpg)

,_Greenwich_Village,_New_York_(49394422401).jpg)

,_Greenwich_Village,_New_York_(29984834725).jpg)

.png)