|

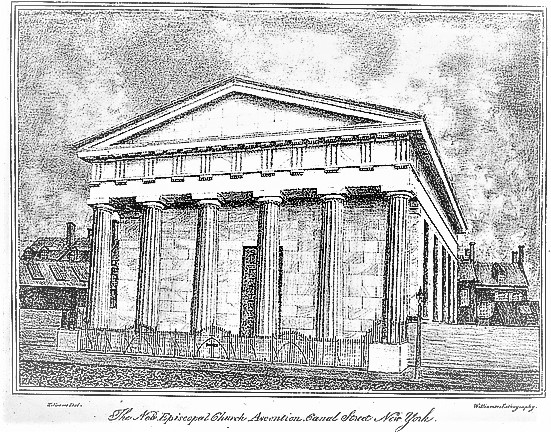

| Published in 1831, two years after the church's completion, signs of encroaching commerce can be seen in the smokestacks in the background, east of Broadway. drawn by C. Burton, engraved by H. Fofsette, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

In 1805 construction began on a 40-foot-wide canal running essentially east-west to drain the Collect Pond, where Foley Square now stands. At the time, the area directly around the canal was undeveloped. But, simultaneously, the new St. John's Park, just a few blocks to the south, was becoming one of New York City's most exclusive neighborhoods. And brick-faced residences of wealthy citizens were inching up Broadway, to the east.

The canal was completed in 1811, but it quickly proved problematic. The slow-moving water smelled and was a breeding ground for mosquitoes. Within a few years, it was obvious that encroaching development was making the real estate valuable. In 1819, the canal was covered over, creating an especially broad 100-foot-wide roadway known as Canal Street.

Early in 1827, a new Episcopalian congregation was formed by a group of about 100 "like-minded people." All were personal friends of the 26-year-old assistant minister of Christ Church on Anthony Street near Worth Street. According to The Churchman several decades later, "Yielding to their persuasions he resigned his charge and on Easter Day the first service of Ascension parish was held in the French church, 'du St. Esprit,' situated on the corner of Pine street, east of Nassau street."

The Church of the Ascension was incorporated on October 1 that year, making it the 11th Episcopal church in New York City. Its members were overall well-to-do and they liberally donated toward the construction of a permanent church building. The site, on the north side of Canal Street east of Broadway, was chosen because, as explained in The Churchman, it was "sufficiently removed from business, and within convenient reach of the majority of the congregation."

The cornerstone was laid on April 15, 1828. The congregation's wealth was evidenced in their choice of architects. Ithiel Town and Martin E. Thompson worked together on the design. Town, who would partner with Alexander Jackson Davis in 1829, is remembered for his work in revival styles. It was most likely his influence that resulted in the Greek Revival temple design of the Church of the Ascension, reportedly the first example of the style in New York.

The church was consecrated on Saturday, May 23, 1829. Six massive Doric columns upheld the entablature and classic pediment. The building so impressed architect Minard Lafever that he included an illustration in his 1830 Young Builder's General Instructor. And six years later, architects Thomas Thomas and John R. Hagarty produced a near-match in St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church on Barclay Street.

|

| The design of newly completed structure was on the cutting-edge of architectural style. Young Builder's General Instructor, 1830 (copyright expired) |

Years later, The New York Times noted, "The parish became numerically strong and soon stood among the foremost in the city."

Despite his young age (or possibly because of it), Rev. Eastman was apparently a firebrand in the pulpit. The New York Times described him as, "in the prime of youth, of more than ordinary zeal and activity." Rev. C. Colden Hoffman recalled in January 1886, "The Ascension Church of that day formed the centre and rallying point of the distinctive evangelism of the Episcopal Church in New York, and might be termed a model of what a church ought to be. From the pulpit there sounded forth the clear distinct notes of the message of the Gospel, which proved edifying to many souls."

One can imagine Eastman's stern, loud voice in what Hoffman called his "unflinching testimony, uplifting the standard of the Cross, opposing all unhallowed compromises with the world, and sounding forth the invitation to all who were willing to follow the Lamb."

The congregants would not enjoy their ground-breaking edifice for especially long. On Sunday afternoon, June 30, 1839, while services were taking place in the sanctuary, a fire broke out in a carpenter's shop in the rear of the church. The Churchman reported, "before the congregation could be dismissed the church was in flames. All that was movable was saved; everything else was destroyed."

The disaster almost became even worse shortly afterward. The Church of the Ascension hired a contractor named Buckhart to demolish the ruins. But he did not work fast enough to prevent a near calamity. Rev. Eastman was the co-plaintiff with the congregation at large in a law suit against Buckhart after a wall collapsed on him.

Their suit alleged negligence "in not taking down the walls of a church...after the rest of the building had been consumed by fire. The walls were much damaged and left in too weak and unsafe a condition to be allowed to remain standing."

Why Rev. Eastman had gone back to the charred pile is unclear, but the suit went on the explain, "A portion [of a wall] was afterwards blown down, burying the plaintiff, while passing along upon the side-walk, in the ruins."

The site of the Church of the Ascension was purchased by the newly-formed French language Church of St. Vincent De Paul. That congregation's new church structure was completed in 1843, to be demolished in 1855 for a modern loft building, which survives.

Despite his young age (or possibly because of it), Rev. Eastman was apparently a firebrand in the pulpit. The New York Times described him as, "in the prime of youth, of more than ordinary zeal and activity." Rev. C. Colden Hoffman recalled in January 1886, "The Ascension Church of that day formed the centre and rallying point of the distinctive evangelism of the Episcopal Church in New York, and might be termed a model of what a church ought to be. From the pulpit there sounded forth the clear distinct notes of the message of the Gospel, which proved edifying to many souls."

One can imagine Eastman's stern, loud voice in what Hoffman called his "unflinching testimony, uplifting the standard of the Cross, opposing all unhallowed compromises with the world, and sounding forth the invitation to all who were willing to follow the Lamb."

|

| A primitive drawing of the church and neighborhood in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York erroneously attributes the design to Alexander Jackson Davis. |

The congregants would not enjoy their ground-breaking edifice for especially long. On Sunday afternoon, June 30, 1839, while services were taking place in the sanctuary, a fire broke out in a carpenter's shop in the rear of the church. The Churchman reported, "before the congregation could be dismissed the church was in flames. All that was movable was saved; everything else was destroyed."

The disaster almost became even worse shortly afterward. The Church of the Ascension hired a contractor named Buckhart to demolish the ruins. But he did not work fast enough to prevent a near calamity. Rev. Eastman was the co-plaintiff with the congregation at large in a law suit against Buckhart after a wall collapsed on him.

Their suit alleged negligence "in not taking down the walls of a church...after the rest of the building had been consumed by fire. The walls were much damaged and left in too weak and unsafe a condition to be allowed to remain standing."

Why Rev. Eastman had gone back to the charred pile is unclear, but the suit went on the explain, "A portion [of a wall] was afterwards blown down, burying the plaintiff, while passing along upon the side-walk, in the ruins."

The site of the Church of the Ascension was purchased by the newly-formed French language Church of St. Vincent De Paul. That congregation's new church structure was completed in 1843, to be demolished in 1855 for a modern loft building, which survives.

|

| photograph by the author |

.png)