In 1858 the neighborhood around merchant William B. Putnam’s

fine brownstone-fronted home at No. 222 Fifth Avenue was quietly

residential. Madison Square park had

been completed over a decade earlier and Putnam’s neighbors were among Manhattan’s

wealthiest and most respectable. The

house next door, at No. 220, had been built simultaneously and, while slightly

narrower, was a near match.

Change soon came to Fifth Avenue above 23rd

Street; and William Putnam’s residence would be a major part of it. Little by little hotels, restaurants and

clubs would wedge themselves into the elite neighborhood; one of the first

being the Traveller’s Club.

Based on the London club of the same name, the Traveller’s

was intended for the convenience of visiting foreigners as well as New Yorkers

who frequently traveled. Founded in

1865, it occupied a house at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 14th

Street. Then, three years later, it moved

into the former Putnam residence.

According to James Grant Wilson in his 1893 The Memorial History of the City of New-York, “To enter the

Travelers’ [sic] a member must have traveled extensively outside of the United

States…It was in the days of its power a great resort for foreigners. In the early years of the club the leading

feature was a series of lectures given by eminent travelers, many of whose

names were to be found in the list of honorary members; and when at No. 222

Fifth Avenue the club gave a brilliant entertainment to the Japanese Embassy,

which attracted great attention at the time.”

Francis Gerry Fairfield focused on English members in his 1873 The Clubs of New York. He described

the clubhouse as “a leading resort for America-examining Englishmen, and the

headquarters of an English coterie of considerable social importance.” He admitted that the club had hosted impressive

receptions and social functions but by 1873 “they have made an end of all that,

having settled into a body as quiet as Mr. Mantilini expected to be after

taking a bath in the Thames.”

The Traveller’s Club left in 1873 and the mansion was

converted for business purposes. The

upper floors were retained as residential space, while the former parlor floor

became home to Howard & Co. jewelers.

The invasion of a retail store, no matter how upscale, was cause for

disgruntlement among the wealthy neighbors.

Decades later The Evening Post Record would recall (although getting the

original retail tenant wrong) that “No. 222 is said to have been the first of

the Fifth Avenue houses above Twenty-third Street leased for business purposes,

having taken in the seventies by Annidown, the hatter, greatly to the annoyance

of near-by residents.”

In fact, James Rufus Amidon lived upstairs at No. 222 and

his hat store would open next door in No. 220 later on. It was the jeweler Howard & Co. who upset

the strictly-residential applecart.

Like all jewelers at the time, Joseph P. Howard’s elegant store

offered more than merely jewelry. Here

ladies could shop for “real bronzes,” china and “fancy goods.” A year after opening, the store offered a new

and “beautiful assortment of Rich Dress Fans;” and just before Christmas in

1875 it advertised that the store would remain open “late Saturday Night” and

that “we opened a beautiful assortment of Worcester and Copeland’s Porcelain,

just arrived per steamer Russia.”

|

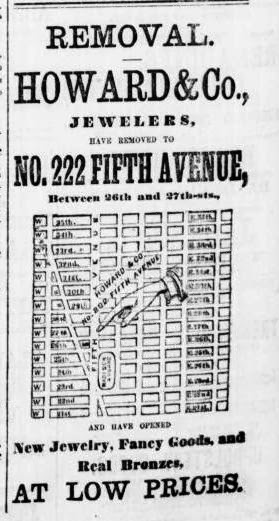

| On announcing that it was moving to No. 222 in 1873, the jeweler cleverly included a map for customers -- the New-York Tribune May 5, 1873 (copyright expired) |

Howard & Co. left No. 222 by 1883 when Wood Gibson moved

in. Before doing so, however, changes

were made for the high-end harness maker.

On September 1, 1883 The American Architect and Building News reported

on “internal alterations” to Nos. 220 and 222 costing $4,000 for lessee Wood

Gibson.

Wood Gibson’s grandfather, also named Wood Gibson, had

established the firm in 1818. By now it not only manufactured quality harnesses, saddles and other carriage and

riding gear; it made high grade traveling trunks. When the two houses were internally connected

for Wood Gibson, a three-story factory was added in the rear.

In 1885 New York’s

Great Industries said of Wood Gibson “The premises occupied are very

commodious, and comprise a splendid salesroom…He makes a specialty of harness

and travelling trunks, and in these lines his goods are unexcelled by those of

any similar concern.” Gibson not only

manufactured his own goods, but heavily imported “fine London saddles, bridles,

holly whips, bits, spurs, etc., which are offered at the lowest prices,

compatible with good workmanship and materials.”

By now James Rufus Amidon’s hat store was sharing space with

Gibson, and would do business from No 220 until at least 1888.

Among the moneyed residents in the upper floors at No. 222

at the time was Warren B. Smith. The

bachelor was a member of the exclusive Manhattan, New York, Riding, and Lawyers’

Clubs. But in 1891 Smith got himself

into trouble with Customs officials when he attempted to smuggle expensive

goods into the country. On June 2, 1891

under a headline reading “It Was Warren B. Smith,” The Sun reported “It was discovered

yesterday that the $5,000 worth of gold tableware, diamond and other jewelry,

and silk underclothing that was found in the trunk of a passenger on the Bremen

steamer Lahn last Friday was the property of Warren B. Smith of 222 Fifth

avenue.”

Smith had sloppily attempted to conceal the loot “in

trousers’ legs and in the bottom of a trunk.”

His indefensible excuse was that he would have declared the articles (valued

at about $125,000 in today’s money), but he “didn’t think the examination would

be so strict.”

Sadly for Smith, the following week the United States

Marshal auctioned off the long list of seized goods.

Fifteen years after opening his store here, Wood Gibson died

in his summer home at Glen Ridge, New Jersey in August 1898 at the age of

67. His obituary noted that “among his

customers were many wealthy persons of this country and of Europe”

Upstairs the commodious apartments continued to be leased by

well-to-do tenants, many of them bachelors.

On June 24 1900 The New York Times mentioned that “W. Marshall Fuller of

222 Fifth Avenue gave a musicale in his apartments on Monday evening. Among the artists were Mrs. Horn, Lily d’Angelo-Berg,

Mary Erver, and Ross David. The

apartment was decorated with white and pink carnations.”

In the meantime the Standard Art Galleries had moved into

the retail space. The firm advertised “household

furniture, rare works of art and bric-a-brac.”

It would not stay long, however.

In January 1902 The Evening Post Record

of Real Estate Sales reported that “The estate of Joseph C. Baldwin has

leased No. 222 Fifth Avenue, a four-story dwelling.”

The new lessee was Joseph Fleischman, who also rented No.

220 on a separate lease. The annual rent

on the 21-year lease for No. 222 was a hefty $12,000. It was announced that Fleischman “intends to

combine the two buildings by making extensive alterations.”

Fleischman commissioned the architectural firm of Buchman

& Fox to renovate the combined store space at Nos. 220 and 222 Fifth

Avenue. The architects replaced the rear

addition of Gibson Wood and added an elevator.

As the alterations commenced, wealthy bachelor Stanton Guion

was living upstairs. The son of one of

the owners of the Guion Steamship Line, Guion was an invalid and had been under

the treatment of Dr. W. B. Clark, the family physician, for several years.

On the morning of April 21, 1902 the 45-year old was already

intoxicated. He picked up his razor and

sliced his throat and wrist. Oddly

enough, he then “rang his bell for a negro attendant, whom he directed to send

for a messenger,” The Times reported the following day. When the servant saw the blood, he instead

sent for Dr. Clark.

As he dressed the man’s wounds, Clark called for an

ambulance from the New York Hospital.

However when Policeman Duffy saw the ambulance arrive and checked into

the problem, he promptly arrested Guion for attempted suicide.

J. F. Douthitt, “a decorator and art dealer,” took the newly

renovated first floor space and the rear extension. The upper apartments were now leased by J.

Ensign Fuller (most likely a relative of W. Marshall Fuller) and his sister;

Mrs. Upperman and her daughter; an actress, Florence Lloyd; and three young

artists; all on the second floor of the combined buildings. On the third floor lived Mrs. Huntington and

her sister (The Times pointed out that “Miss Huntington is a relative of the

late Collis P. Huntington); and two unmarried women, Misses Penfield and Leiter

(“Miss Leiter is a member of the Chicago family of that name,” said The Times).

Among the tenants on the top floor was Captain

E. L. Zalinski, “inventor of the dynamite gun” and his nephew, S. L. Adler.”

Around 3:00 in the morning on April 10, 1903 a fire broke

out in the rear extension. Joseph Rodriguez,

the elevator boy, first saw the flames and roused the janitor, William H.

Harris. By the time the firemen arrived,

Harris had directed most of the tenants out of the building; but others were

still inside.

On the top floor, Mrs. Higginson and her daughter were

trying to capture their two Angora cats in a basket. Policeman Duffy ordered them out; but the

women refused to leave their pets. The

standoff ended with Duffy and two firemen corralling the animals. At the same time Captain Zalinski refused to

leave some of his gun models in the burning building. Captain Farley of the fire department ended

the argument by removing the inventory down the stairs.

Several of the female tenants swooned and had to be carried

out by firemen. When it was all over no

one was seriously injured; however there was $70,000 damage to the recently

renovated structure, most of which was in Douthitt’s gallery. In addition to valuable paintings, he lost “many

engravings, draperies, and tapestries.”

Douthitt left No. 222.

The combined buildings were now converted to retail space

throughout. L. P. Hollander & Co.

moved in. The firm offered women’s and

children’s clothing to the carriage trade.

The store would stay only five years.

On February 10, 1909 it announced it would relocate to Nos. 550 and 552

Fifth Avenue where it planned a new 8-story building.

|

| Hollander & Co spread its store through three full floors -- the New-York Tribune, September 25, 1904 (copyright expired) |

In 1911 Charles Josephson leased the store and basement

here; but the Joseph C. Baldwin estate which still owned the building soon had larger

plans. The outdated brownstone front was

obviously a remodeled home. To attract

new commercial tenants, a modern-looking structure was called for.

Architect John C. Westervelt stripped off the old façade and

created an up-to-date limestone and cast iron façade. The make-over was completed in 1912. No longer connected to its neighbor, the

resulting structure, was tasteful and inviting to modern commercial tenants.

Throughout the first three decades of the century the

building would house various tenants. In

1936 it was called “Music Box Hall” and was headquarters to trade unions and labor

organizations. Later that year the

entire building was leased by the Book Mart and the following year on January

15 Benjamin Duckman, “retailer of books, lamps, pictures and art goods,” leased

the building.

Duckman apparently had a change of mind and two weeks later

the building was leased to the Shapiro & Son company, manufacturers of curtains

and bedspreads. Only a week after

Shapiro & Son moved in, the building was heavily damaged by fire. On February 3, 1937 The New York Times

reported “Four firemen were plunged into four feet of water when a section of

flooring collapsed beneath them in a fire in the five-story loft building at

222 Fifth Avenue.” The newspaper said “Firemen

poured tons of water into the basement, after breaking through sidewalk lights

with sledge hammers.”

Despite the catastrophe, Shapiro & Sons would still be

in the building in 1966 when its president, Charles Shapiro, died at the age of

76.

In 1946, after owning the building for 88 years, the Joseph

C. Baldwin Estate sold No. 222 for $110,000 to the Elk Supply Company. The new owners immediately began a

conversation which resulted in offices on each floor above the store

level. Along with Shapiro & Sons, the

building would be home to a diverse mix of tenants including the Posner

Advertising Agency in 1947; the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade in 1962; and

ActBig.com, a start-up internet company in 2000.

Today No. 222 Fifth Avenue enjoys compassionate maintenance

by its owners. An architecturally-sympathetic

street level renovation and few alterations above the first floor preserve John

C. Westervelt’s handsome Edwardian design.

photographs taken by the author

.png)

According to author TJ Stiles in the Pulitzer Prize winning Custer’s Trials, General Custer stayed here shortly before his “last stand”.

ReplyDelete