Road construction seems to have caused confusion among delivery drivers in this photograph. from the collection of the Library of Congress.

A two-story flour warehouse stood on the corner of South and Whitehall Streets when Captain John Cole purchased it from Anthony Lispenard and his wife in 1790 for $1,750 (about $53,500 in 2023). Thirty years later, in 1820, Cole would begin renovations to convert the warehouse into an inn, called the Eagle Hotel. According to The New York Times decades later, "The tale is that Captain Cole had returned discouraged from an unsuccessful trading trip to South America and was forced to sell his packet [i.e., ship]. Some of his comrades suggested that he build a hotel where the skippers of packets could gather to spin yarns."

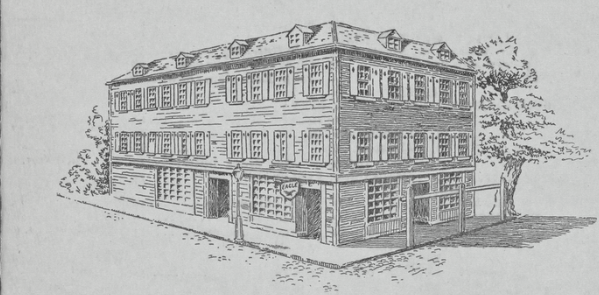

Cole's two-year renovation resulted in the three-story and attic Eagle Hotel. In his packet ship had been great mahogany beams, loaded as ballast. They were now used for the framing of the inn. The Federal style architecture included multiple-paned windows at street level, and small dormers that pierced the attic.

The original appearance of the Eagle Hotel, from a 1914 Eastern Hotel menu. from the collection of the New York Public Library

Cole leased the Eagle Hotel to Frank Foot, who opened it on May 9, 1822. The Sun later mentioned that "Frank Foot, its first boniface, was a relative of Daniel Webster." The location proved to be immensely beneficial. The hotel was near the bustling harbor, convenient for travelers and seamen, and amid the cluster of downtown business buildings, making it a favorite among shippers and other businessmen.

A menu decades later would boast, "One of the Eagle Hotel's earliest patrons was Robert Fulton, the inventor of the first steamboat--the 'Clermont.'" The author was apparently unaware that Fulton had died in 1815, seven years before the Eagle Hotel opened. Nevertheless, there was no shortage of celebrated patrons of the hotel tavern. Among the well-known figures who reportedly met there were Cornelius Vanderbilt I, Daniel Webster, and General Winfield Scott Hancock. Not all of the guests, of course, were men. When Swedish singer Jenny Lind appeared at Castle Garden in 1850, she stayed at the Eagle Hotel.

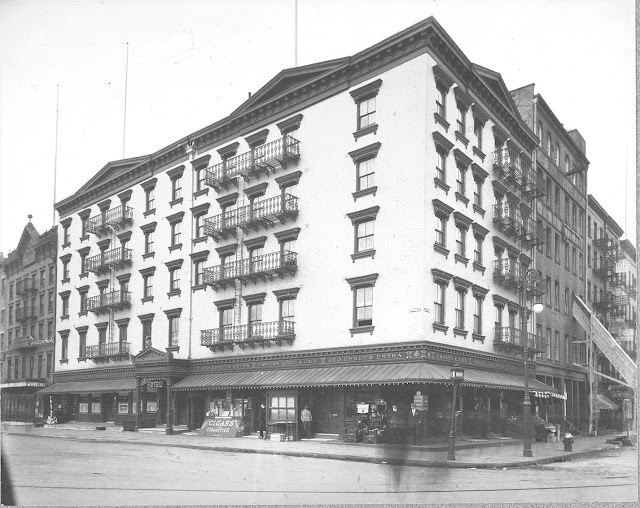

In 1858 Foot enlarged the structure by adding two full stories. (The 1939 New York City Guide disputes that date, saying it was 1856.) The Italianate style design included a pedimented cornice, molded lintels, and a handsome entrance portico. The alterations were completed about the same time the grand iron ship the Great Eastern was launched in Great Britain. The vessel would eventually be used to lay the Transatlantic Cable. In its honor, Foot named his renovated hotel the Eastern.

In 1869 showman P. T. Barnum exhibited the Cardiff Giant in Castle Garden. The "petrified man" was purported to have been excavated by workers digging a well in Cardiff, New York. An advertisement for the Eastern Hotel in 1906 would recall, "Barnum was perhaps over-careful that no one got too familiar with his 'cement man,' and the huge figure was toted across from Castle Garden and roomed under lock and key in the Eastern every night."

The quiet of the Eastern Hotel was broken on July 30, 1871. At 1:30 that afternoon the Staten Island ferryboat the Westfield exploded in her slip at South Ferry. The New York Times reported, "In an instant of time hundreds of human beings were killed, or maimed, or scalded. Aged men and women, matrons and men at the threshold or in the middle passages of vigorous life, happy, laughing children, and cherub babes in the arms of doting parents, were alike involved, and were the victims of a catastrophe so terrible that it cannot be described."

Bodies and victims quickly filled the available wagons and carriages. The Eastern Hotel was made a sort of triage center. A reporter from The New York Times walked through the public rooms, writing in part:

The first sight that presented itself was a woman kneeling over the insensible form of a man, which lay stretched out on the floor. The face and arms of the woman were badly scalded, and her whole dress has a draggled appearance as if she had been drenched in steam; but utterly unmindful of self she was busy fanning the face of her husband, which showed through its covering of flour that it had been fearfully burned.

At 2:00 on the morning of April 17, 1894 a fire broke out in the hotel's barroom. A night watchman ran throughout the building, pounding on every door and rousing the 150 guests. One of them, professional boxer John M. Laflin had just arrived in New York. It took a few moments for him to realize what was going on. Still groggy from sleep, he climbed out his window and down the fire escape. He was embarrassed later, saying, "As soon as I recovered my presence of mind I found that my toilet had been made without reference to comfort or decorum. I had on only my 'stovepipe,' a pair of trousers and an undershirt."

The blaze was confined to the barroom. The Evening World estimated damages at $25,000 (about $812,000 in 2023). "The painting and decorations on the ceiling alone cost $40,000," said the article.

Horse-drawn street cars crowd the street in 1906. photo by Byron Company, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

At 5:00 on the morning of March 15, 1909 clerk William Hubel reported for work, only to discover the body of the night clerk, Isadore De Valant. The money drawer had been emptied of $3,000 in cash and Valant had been robbed of his gold watch, scarfpin, shirt stud and $150. His throat had been slashed and his skull fractured.

The New York Times reported, "Fully fifty detectives scattered themselves along the water front saloons and docks and about the Battery yesterday and last night in a search for the perpetrators of a murder so reckless and savage as to startle even the oldest hunters of criminals." It did not take them long. The first arrest was made on the afternoon of March 15.

In its 1917 edition, Valentine's Manual of the City of New York noted the changes in the hotel after nearly a century. Calling it "almost forgotten by old New Yorkers but still doing business," the article said that the Eastern "has passed through its various phases as a fashionable hostelry to the present time, when it is largely used as a restaurant and a place for the accommodation of transient travelers."

After having owned the property for 128 years, in 1918, the estate of Captain John Cole sold the Eastern Hotel to John Bittner. On January 28, The New York Times reported "The old hotel will be torn down within a few months." Bittner had announced plans "for a ten-story hotel, with 200 rooms" on the site.

For some reason, however, Bittner never moved forward with his plans. On May 9, 1919 he held a 97th anniversary dinner for 100 former guests, and the following day he entertained between 50 and 60 old sea captains, "six or seven of them from Sailors' Snug Harbor," noted The Evening World.

The celebrations were held on the brink of the enactment of Prohibition. And like so many restaurants and hotels, the law crippled the nearly century-old establishment. On January 18, 1920 The Sun reported, "Prohibition has dealt the Eastern Hotel, the oldest hostelry in the city, at Whitehall and South streets, so heavy a blow that both bar and restaurant are to be closed at the end of the month. A United Cigar store probably will occupy the spot now ornamented by the big mahogany bar." Bittner assured that the upper floors would continue to be operated as a hotel.

In 1920 the ground floor was made over for commercial shops. The Nautical Gazette, April 20, 1920 (copyright expired)

Instead, Bittner sold the property that year to the Brown family. By the Depression years the hotel rooms had been remodeled into office space. The venerable and embattled structure continued on as such until the summer of 1963. On July 12, The New York Times reported that Ernest Brown, "in whose family it had been held for 43 years," had sold the building to a group of European investors. "The building will be remodeled at a cost of $225,000," said the article. But, instead, it was replaced the US Coast Guard Recruiting complex.

many thanks to historian Anthony Bellov for suggesting this post

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment