photo by Momos

The 1862 Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York recalled, "After the Revolutionary War a notification was received from the Congress of the United States that they intended to sit in New York, whereupon the Common Council tendered to them the use of the City Hall." The current building proved insufficient, said the article, and so "A committee was appointed to report a scheme for a new City Hall, but many years elapsed before this design was brought to a practical result."

The Common Council received a proposal in May 1800, and on May 26, 1803 the cornerstone of the new City Hall was laid "in presence of a large concourse of spectators," according to the New-York Evening Post. The stone included the names of city officials, as well as "John M'Comb, jun. architect."

The 40-year-old John McComb Jr. was New York's preeminent architect of the day, the son of well-known architect and surveyor John McComb Sr. The City Hall building would be one of his masterpieces.

The New-York Evening Post wrote:

The length of the New Hall will be 216 feet, and the average depth about 100; to be built of cut-stone, the basement rusticated; the first story to be of the Ionic order, with columns and pilasters; and the upper story of the Corinthian order. The ends and rear to be ornamented in an elegant manner.

As the building rose, in 1805 Longworth's Directory provided an update. "The new City Hall...will be, when finished, superior to anything of the kind in America, and will vie with the public buildings in Europe. It is situated in front of the [City Hall] Park, near Broadway." At the time, the foundation was finished, but the directory cautioned, "it will be some years before the building will be completed."

Indeed, City Hall would not be fully completed until 1812--this despite Martha J. Lamb's writing in her 1877 History of the City of New York, "workmen had been employed upon it almost without intermission since the corner-stone was laid." Although not yet completed, historian R. S. Guernsey noted in 1889 that it "had been occupied in part since July 4, 1811."

It would hold, he said, "the chief city offices, and the State and city courts," adding, "In the cupola was a bell, smaller than the usual church bell, which rung on court days to summon attendance at the opening or convening of the principal courts."

Sitting at the north end of City Hall Park, the building was on the northern hem of the city. aquatint by W. G. Wall, 1826, from the collection of the NYC Design Commission

John McComb Jr. had produced a Federal style structure that two centuries later would be recognized as superb in its proportions and elegant in its details. Working closely with him was French-born architect Joseph F. Mangin, who is widely credited for the delicate French influences, seen both on the exterior and within the central rotunda.

Martha Lamb flatly pronounced, "It was the handsomest structure at the time in the United States." The white marble of the front and sides had been brought from Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Because the building sat this far north, according to Lamb, "a dark-colored stone was thought good enough for the rear of northern wall, since 'it would be out of sight to all the world.'" Standing atop the cupula was a statue of Justice. Not including furnishings, the structure had cost "half a million of dollars," according to Lamb. That amount would translate to about $10.5 million in 2023.

The interiors were no less impressive. Upon entering, Lamb described "a large circular stone staircase, with a double flight of steps upheld without any apparent support." The rotunda was "ornamented with stucco in novel designs, and lighted from the sky with fine effect. She described the Council Chamber as:

...richly ornamented with wood and stone carvings, and the chairs provided for the mayor the same that had been used by Washington while presiding over the first Congress in New York City; it was elevated by a few steps on the south side of the room, and graced with a canopy overhead.

Public buildings were "illuminated" for important occasions, and the first illumination of the City Hall came in 1814 to celebrate Oliver Hazard Perry's victory in the Battle of Lake Erie. Painted glass panels, called transparencies, were placed in some of the windows. While the effect must have been stunning, the threat of fire was immense. Military historian Rocellus Sheridan Guernsey wrote in 1889, "On that evening the City Hall front was lighted at every window from basement to cupola. The illumination consisted of placing several rows of lighted candles in regular order at each pane of glass in every window." He continued...

...it consisted of a total of 1,542 wax candles and about 450 lamps, giving effect to the transparencies, and about 310 variegated lamps. These latter were placed on the outside along the edge of the roof and about the cupola and over each window and door, and around the balcony and portico; some were in arches and others in lines appropriately and effectively arranged.

Along with the expected city offices and courtrooms, there was one department that might be surprising to 21st century minds. The 1834 directory New-York As It Is listed the "Lost or stray children deposite" in the building. (A "deposite" was the now-disused term for a place to commit items--in this case children--for trust and care.)

Near disaster occurred in 1858 during a pyrotechnic display celebrating the laying of the Trans-Atlantic Cable. The City Hall dome caught fire and significant damage was caused before the blaze was extinguished. It may have been the necessary repairs that prompted architect Charles F. Anderson, who had designed the extension of the Capitol building in Washington, to write to The New York Times in August 1858, suggesting more encompassing renovations.

He opined, "This structure was never a good architectural outline. There is nothing striking or characteristic about it." To "obviate" its defects, he suggested a long list of improvements. Among them he proposed to raise the building to three stories and "take away that miserable porch, and put a grand projecting portico, surmounted by a pediment, running the entire height in front." Instead, the city limited its focus to repairing the dome, its restoration headed by architect Leopold Eidlitz.

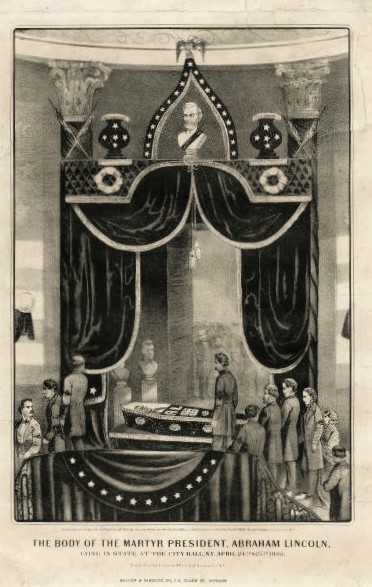

The double staircase in the Rotunda saw a steady stream of mourners who climbed to pay their respects to the deceased President Abraham Lincoln on April 24 and 25, 1865. The New York Times reported on April 25, "The early part of the day witnessed an eager, impatient, but perfectly orderly body of people crowding on the line of the procession and around the City Hall." The article estimated the wait at "fifteen or more consecutive hours."

Lincoln's bier in the Rotunda. Currier & Ives, 1865, from the collection of the Indiana State Museum

A second U. S. President would lie in state in the Rotunda 20 years later. On August 7, 1885 the casket of Ulysses S. Grant arrived in New York and was brought to City Hall. It was placed at the foot of the staircase. New Yorkers filed past from 6:00 that morning until an hour after midnight.

A photograph "made by electric light" by Hill Bros. of Grant lying in state was sold as a cabinet card souvenir. from the National Park Service Manhattan Historic Sites archive.

In 1892 a serious threat loomed. King's Handbook of New York City said, "The City Hall has been in its time the finest piece of architecture in the country, but it is surpassed now by many buildings of more imposing structure...A new city hall will be one of the architectural attractions of New York in the future." The article noted that a push was ongoing to build a modern City Hall on the site of the old Crystal Palace known as Reservoir Square (today's Bryant Park).

By the time this photograph was taken in 1886, the downtown Manhattan had engulfed City Hall. The brownstone back, never expected to be seen, had by now been painted to simulate marble. from the collection of the New York Public Library.

On February 19, 1893 The New York Times weighed in, agreeing that "the general feeling is undoubtedly that the old building 'must go,'" but stressing that "its architectural and historical value entitle it to preservation and to re-erection elsewhere." (The very idea of historic preservation at the time, not related to battle sites or homes of important figures, was essentially unheard of.)

Thankfully, Mayor Abram Hewitt proposed preserving the 1812 building in sito and erecting a municipal building nearby. His successor, Mayor Franklin Edson, agreed, refusing to "mar" the existing building and its proportions by altering and enlarging it. Construction for the current Municipal Building began in 1907.

The venerable City Hall building was given several brush-ups. The City Council Chamber was renovated in 1904 by William Martin Aiken (it had originally be reworked in 1897 by architect John H. Duncan); and the firm of Bernstein & Bernstein redecorated the Governor's Room in 1905-1907. Unfortunately, their work was so abhorrent to most that the space was immediately restored to its original by Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage.

The Governor's Room in 1830. drawing by Charles Burton from the archives of the NYC Design Commission

In 1966 the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated City Hall an individual landmark, and ten years later designated the Rotunda an interior landmark. In doing so, the commission described the Rotunda as "a sensitively designed and beautifully proportioned interior space, a notable feature in a building of great elegance and serene dignity."

photo by MariekeSlagter

In 2010 renovations being done in the basement turned up major deterioration of the infrastructure. A comprehensive restoration project was initialized to stabilize the structure. The five-year undertaking expanded to the conservation and documentation of the artwork, including the City Council Chamber ceiling and the mural series by Taber Sears executed in 1903.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

The brownstone rear, along with all the original deteriorated Stockbridge, Massachusetts marble facade and sides, was replaced with Alabama limestone between 1954 and 1956

ReplyDeleteAnother well-researched article. Thanks, Tom.

ReplyDeleteThank you!

DeleteThe hideous committee-designed Old Post Office building took up the entirety of what's now the park just south of City Hall in the late 1800s. Finally torn down in the early part of he 20th century when the PO moved to 8th Avenue. Meanwhile, in front of City Hall was the terminus for the streetcars that went across Brooklyn Bridge to what's now Cadman Plaza Park in Brooklyn. This enormous structure was finally removed in the 1940s. I'm sure there are numerous photos of these available on the Internet.

ReplyDeleteThat is a rather uncharitable description of the Old Post Office.

DeleteIt was a stately and fine example of the Second Empire Style—executed on a unique trapezoidal site and at great scale! It’s nearest rival could only be the Old Executive Office Building in Washington.

Although its site occupying the apex of the City Commons was perhaps poorly chosen, the demolition of the Old Post Office was a terrible loss to the architectural heritage of lower Manhattan.