|

| photograph by the author |

The Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide pointed out, "The Vanderbilt plot has been used by the Inter-Club Baseball Association during the last winter, and games were played there several times a week, weather permitting."

The baseball organization and Senator Aldrich would soon have to fine other accommodations. A few years earlier the Burden and French families had formed a syndicate with plans to demolish the mansion and erect a lavish apartment building on the two properties. Cass Gilbert had prepared plans for the structure. But backlash from the millionaire neighbors put a halt to the project.

Now new owners had resurrected the idea. The Guide noted they "will improve the site with a twelve-story apartment house, which will have specially designed suites to met the desires of the prospective tenants. The entire investment, including the cost of the building, is estimated to be in the neighborhood of $3,000,000." That figure would be more like $73 million in 2016.

On October 2, 1915 The Record & Guide explained "Apartment houses in the exclusive section of Fifth avenue? Yes, although prior to the completion of the one at 998 Fifth avenue, the mere thought of such a possibility struck horror to the hearts of the residents of that thoroughfare."

The site was, indeed, squarely amid the palaces of Manhattan's wealthiest citizens. Directly across 72nd Street were the homes of Oliver Gould Jennings, James Stillman (in the former Henry T. Sloane house), and nearby lived Louis C. Tiffany, Henry A. C. Taylor, W. Bayard Cutting and Nathalie E. Baylies. One block to the south on Fifth Avenue was the newly-completed home of Henry C. Frick.

Architect J. E. R. Carpenter (who was also an investor) received the commission. The Record & Guide described him as having "a wide experience in the design of multi-family houses of the better class." This one, however, would be his crowning achievement.

|

| A 1917 advertisement depicted the completed building. Real Estate Record & Guide March 31, 1917 (copyright expired) |

His 12-story, limestone-faced building was Italian Renaissance in style. The owners, 907 Fifth Avenue Company, promised "Throughout the structure workmanship and materials will be the finest obtainable." And that would have to be so--in general there was no more than one apartment per floor. There would also be duplexes and triplexes available. "The individual suites will consist of from 14 to 30 rooms, having five to nine bathrooms," noted The Record & Guide.

The journal said "The architect has borne in mind that the tenants of this building will no doubt entertain largely and he has reserved sufficient space for that purpose." To that end, some of the largest apartments included a ballroom.

Regarding the "servant problem," Carpenter designed "comfortable and cheerful rooms for the servants." In addition, tenants could lease additional rooms for butlers and valets in another part of the building.

The original tenants were able to dictate the style and decoration of their apartments. Those signing leases while the building was under construction could choose the wood finishes, wall hangings, lighting fixtures and other elements. Living at 907 Fifth Avenue would not come cheaply. The least expensive apartment would cost $10,000 per year; a full floor apartment $30,000 (nearly $61,000 per month today).

On August 5, 1915 the New-York Tribune described certain amenities in Carpenter's plans. Regarding the central courtyard, it reported "This court will be treated architecturally in the Italian style and will give an air of spaciousness as one enters the building." As for the apartments themselves, the article noted "The rooms are of unusual size the drawing room being 21x38 feet and the dining rooms 20x26 feet. The larger apartments have rooms for sixteen servants, while the others have rooms for seven and eight servants."

Moneyed New Yorkers were quick to sign leases. On December 4, 1915 Herbert L. Pratt, Vice President of the Standard Oil Company, took a 28-room apartment. In January 1916 a "prominent New Yorker" leased a 23-room, six bath apartment," and in March Charles A. Stone, President of the American International Corporation signed a lease for the largest apartment--30 rooms, including seven baths. By now other apartments had been taken by Daniel G. Reid, Mrs. Paul Morton, Victor Morawetz and Henry Sanderson. The building's architect and his family were also residents.

Mrs. Marcus Daly got one of the last leases, signing for her 16-room apartment in December. Henry F. Sinclair, founder of Sinclair Oil Company, was another of the late renters, as was General Motors executive Billy Durant and his wife, who moved in in 1917.

The completed structure was not only the most exclusive apartment building in Manhattan, it was architecturally one of the finest. J. E. R. Carpenter was awarded the 1916 Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architecture for the design. A decade later he would receive a Diploma of Merit from the International Exhibition at Turin for the building.

For several years 907 Fifth Avenue appeared in the newspapers only as millionaire tenants gave dances and dinners, debutante entertainments, and weddings and receptions. As they closed their Fifth Avenue apartments for the summer, newspapers followed them. George Rives, Corporate counsel of New York City, and his wife, Sara, summered in their Newport estate; the aging E Matilda Ziegler, widow of baking powder mogul William Ziegler, had a summer residence in Noroton, Connecticut. Her husband had left a fortune of more than $13 million in 1905.

It was Daniel G. Reid who first brought an unwanted spotlight to the exclusive address. Reid had managed to monopolize the tin plate industry, earning himself the name "The Tin Plate King." He had an eye for actresses and by the time he moved into 907 Fifth Avenue, he was on his third wife, former showgirl "and Casino favorite," Mabel Carrier.

|

| Millionaire Daniel G. Reid had an eye for the showgirls. photo from the collection of the Library of Congress |

The Reids maintained an additional apartment in Paris, and a summer estate in Irvington, New York. The Fifth Avenue apartment was filled with priceless antiques and artwork, and Margaret Reid (as she was now known) enjoyed a lavish lifestyle. Her husband gave her a $12,000 automobile for Christmas in 1919; and her custom-designed French underwear was valued at $2,000.

It was that underwear that would cause upheaval in the Reid household. Margaret Reid's dressmaker was Madame Gorgette, an attractive divorcee. Margaret's personal maid, Amanda Gunnerson, later revealed "Madame Gorgette got into the habit of coming in to the Reid apartments to show Mrs. Reid samples of lingerie, and that she often interested Mr. Reid in these creations."

Daniel G. Reid, it turns out, was very interested in the frilly underthings.

Amanda Gunnerson testified that on one occasion the modiste arrived only to find that Margaret had gone to the theater. She nevertheless displayed the lingerie to Daniel Reid, who asked if she had brought "any models." Allegedly, Madame Gorgette replied "No, I prefer to be my own model."

The maid said that then, "Madame Gorgette showed Mr. Reid a transparent petticoat."

|

| As Mabel Carrier, Margaret C. Reid was "the centre of lavish attention," according to The Evening World on March 1, 1919 (copyright expired) |

Things got steamier after Margaret Reid left on the morning of December 5, 1918 for a week in Atlantic City. Her good friend and dressmaker, Madame Gorgette, accompanied her to the train station, then turned around and returned to the Reid apartment. She did not leave the entire week.

Infuriated, Margaret Reid sued for divorce. The scandalous affair made headlines long after the divorce was granted on February 26, 1920. The Evening World said it took the jury less than five minutes to award the divorce to Margaret. The judge had instructed that "the only question to be answered was whether or not Reid, between Aug. 24, 1910, and June 4, 1919, had been unduly intimate with various women. This question was answered in the affirmative."

Despite her $200,000 award and $30,000 per year alimony, Margaret wanted more. On May 8, 1920 she sued for $325,000 worth of "several hundred items of furniture, household articles, wearing apparel and art objects" in the Fifth Avenue and Irvington residences; and $15,000 in furnishings of the Paris apartment, which Reid retained in the court decision.

Margaret's list of items filled 15 pages. Certain of them were clearly understandable--her furs and gowns, for instance. Others including oil paintings, Flemish tapestries, and Italian Renaissance period furnishings required discussion. But neither Margaret nor Daniel Reid would relent on two items: a $30,000 painting of King George I, by Sir Thomas Lawrence; and their pet Pekingese purchased in London.

Reid offered to pay his ex-wife the value of the dog and portrait, as he had done for the silverware, linens, china, and antiques. But her lawyer said that she "valued that painting personally in such a way that she will not consent to part with it for any consideration. It is that way, too, with the 'Peke.'" The bitter contest lasted through 1921.

The ugly affair, publicized in newspapers nationally, took a serious toll on the millionaire. He was repeatedly treated for health problems and traveled to White Sulphur Springs to recuperate. In August 1924 his doctor, Charles F. Stokes, explained "the dominating feature" of Reid's case "was chronic alcoholism with acute exacerbations brought about by stresses incident to his marital difficulties."

On January 17, 1925, after having been bedridden in his apartment for about a week, Daniel Gray Reid died of pneumonia at the age of 66. His estate was valued at approximately $50 million.

Another of the wealthy residents of No. 907 during the messy Reid affair was Russian Prince Vladimir Nicolaievitch Engalitcheff. Known popularly as Val, his family had escaped the Bolsheviks. On August 31, 1922 The New York Times informed readers that the Prince "has returned from abroad and is now at 907 Fifth Avenue." On that voyage he and his wife, a Chicago heiress, had made friends with author F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda.

Within six months the 21-year old Prince was dead in his Fifth avenue bedroom. His obituary gave heart disease as the cause of death. But, according to Sarah Churchwell in her Careless People: Murder, Mayhem, and the Invention of the Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald noted in his January 1923 ledger "Val Engalitcheff kills himself."

Newspapers, naturally, followed the scandalous divorce, the mysterious royal death, and other attention-grabbing stories; like the the $200,000 suit filed by Mrs. Mabel Gunther in 1922 against residents Carl Vietor and his wife (she charged them with alienating the affections of her two teen-aged children whom, she said, the Vietors conspired to "make German") and the 1926 suicide of the Charles Stone family's governess, Nancy Bamlet, who threw herself from an 11th story window on January 21, 1926.

|

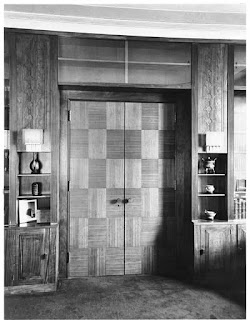

| Before Mrs. Charles J. Liebman moved into her duplex apartment, she had it remodeled in Art Deco style. photos by Sigurd Fischer from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

So when Anna Eugenia La Chapelle Clark and her daughter moved into No. 907 Fifth Avenue in 1926, it drew little notice. Like Mabel Carrier, Anna had been a showgirl before she met former Montana Senator and copper tycoon William C. Clark. When the much-despised millionaire died in his gargantuan mansion on Fifth Avenue and 77th Street on March 25, 1925, Anna Clark wasted little time in searching for new accommodations.

Anna and her daughter, Huguette Marcelle Clark, moved into a 14-room apartment which included four bedrooms. According to Meryl Gordon in her The Phantom of Fifth Avenue, "In November 1926 Anna went on a spending spree to decorate the new abode, buying antiques from the London firm Charles, including a $3,500 Queen Anne walnut wing chair with needlepoint and a $4,000 William and Mary sofa covered with seventeenth-century tapestry. She also spent $13,500 for a Louis XV sofa and five armchairs, and ordered thirty yards of blue chenille carpet for Huguette's suite of rooms. The soothing color matched Huguette's eyes."

|

| The Clarks' 12th floor apartment --floorplan via Brown Harris Stevens |

Hugette was born in 1903, two years after her sister Andree. Although Clark reported that he and Anna had secretly married prior to the first pregnancy, no documentation was ever found. Huguette's legitimacy was, therefore, long a matter of speculation. The $150 million estate left by her father, however, prompted society to ignore the issue.

By the time the Clark women moved in, J. Edwin R Carpenter had become President of the 907 Fifth Avenue Company. He and his family still lived here, and on October 22, 1921 the wedding of daughter Marion Stires Carpenter to Milton Dorland Doyle took place in the apartment. Now, the same month that Anna Clark was shopping for furnishings, Carpenter sold the building to William Ziegler, Jr. for $3.25 million.

Huguette, in the meantime, was visible in society. That same month, on November 22, 1926, she hosted a debutante luncheon at Pierre's for Carolyn Storrs. (Carolyn was the daughter of Frank Vance Storrs, the founder of Playbill.) Huguette's own introduction to society happened that same season.

|

| Huguette (left) and her mother, Anna. photo via finda grave.com |

The following year, on December 13, 1927, Anna Clark announced the engagement of Huguette to William Macdonald Gower. The Times noted "The engagement is of wide interest to society here and in California." In preparation, Anna leased and decorated an 8th floor apartment for herself, so that the newlyweds could take over the 12th floor suite.

All of New York society anticipated a fashionable Fifth Avenue wedding. Instead, Huguette and Gower were married quietly in the Clarks' Santa Barbara estate, Bellosguardo, on August 17, 1928. A local newspaper explained "The wedding will be extremely quiet, with only members of the family present and there will be no attendants."

The wedding, in fact, was nearly an arranged marriage. Anna Clark agreed to pay William Gower a $1 million dowry. And the sheltered Huguette had not been prepared for marriage. Not realizing what sex was about, the wedding night was disastrous. According to biographer Meryl Gordon, she later told a confidante, "It hurt, I didn't like it."

Although the couple moved into 907 Fifth Avenue and appeared in public as Mr. and Mrs. William MacDonald Gower, Huguette focused on her painting. (Seven of her works had been exhibited at The Corcoran Gallery from April 28 to May 19, 1928.) But domestic life was not good in the 12th floor apartment.

On June 23, 1928 The New York Times mentioned "Mrs. William Andrews Clark and Miss Huguette Clark of 907 Fifth Avenue will leave late next week for Santa Barbara, Cal., where they will remain for the Summer." No mention was made of Bill Gower and society column readers could not have missed the fact that Huguette was using her maiden name.

She and her husband separated in 1929 and divorced in Reno on August 12, 1930. She claimed desertion and he said that the marriage had never been consummated. The New York Times reported "Her mother accompanied her to Reno and they brought half a dozen servants, including a butler and a secretary, with them."

The exclusive apartment building was thrown into panic on July 22, 1931. Most of the sprawling apartments were closed for the summer as the residents went off to their country estates. The family of Cornelius F. Kelley, President of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, had recently left for Butte, Montana. Their 23-room duplex apartment was filled with "a library of many books, works of art, and valuable furniture," according to The Times.

By the time smoke was discovered seeping out of the apartment that morning, a fire had made substantial headway inside. Firemen found "the foyer, the huge music room, and the library a mass of charred ruins. The costly carved oak paneling on the walls was glowing charcoal. All that remained of a grand piano were the metal strings The morocco-bound works of famous authors were paper embers."

Although the Kelley apartment suffered $200,000 in damages; no other apartments were affected. Samuel Herzog, owner of the building, said "the fireproof structure, one of the finest in Fifth Avenue, had stood the test."

Although Anna Clark's name continued to appear in the newspapers as she made generous charitable donations over the decades, both she and her daughter withdrew from society. There were no entertainments given. Nevertheless, one staff member, according to Warren Allen Smith's Unforgettable New Canaanites, "thought the two were not 'odd or strange,' but rather 'quiet, loving, giving ladies. Allegedly distrusting outsiders as well as her family thinking that they were after her money, [Huguette] conversed in French because others would likely not understand."

In October 1950 the owners of the building began a "remodeling operation" which would more than double the number of apartments. It was a nice way of saying they were dividing the mansion-sized apartments.

Anna Eugenia La Chapelle Clark died in her apartment on October 11, 1963 at the age of 83. Huguette lived on at No. 907 Fifth Avenue, keeping the 12th floor apartment and the two which made up the 8th floor, including her mother's. She had, in total, 42 rooms in the building.

By now she had essentially been lost to society's memory, and she withdrew into her personal reality. Along with her painting, Huguette occupied her time with doll collecting--a collection valued in the millions of dollars by the time of her death.

The last residents and staff of 907 Fifth Avenue would see of Huguette Clark was in 1991 when she was admitted to Beth Israel Medical Center for skin cancer. Following treatment she decided to live there. Her Fifth Avenue apartments, her Santa Barbara estate, and her country residence in New Canaan, Connecticut, were staffed and maintained for decades as if she would be returning the following day. (She bought the Connecticut residence in 1951, but never slept a night there.)

Building staff at 907 Fifth Avenue were instructed to accept packages, flowers and mail as if she were still there. No information was to be given out regarding her whereabouts or condition.

The name of Huguette Marcelle Clark would be finally thrown into the spotlight following her death, just two weeks before her 105th birthday. The public was consumed by the story of the eccentric recluse who left an estate of $400 million.

In 2012, even while her estate was being hotly contested, the three apartment were put on the market for a total of $55 million.

Despite the 1951 downsizing of the apartments, 907 Fifth Avenue continues to be one of Manhattan's most exclusive addresses. And J. E. R. Carpenter's award winning design continues to draw praise.

photographs by the author

many thanks to reader John Chalupa for suggesting this post

.png)

This was my absolute favorite post you've ever done.

ReplyDeleteInteresting post! The story of Huguette Clark and her family is an amazing one, well told in the bestselling book Empty Mansions." It's much more readable and factual than the Gordon book.

ReplyDeleteThis was one of the grandest buildings on the island prior to the 1950's remodeling.

ReplyDeleteThe first 5 floors held 2 simplex apartments each.On the floors 6-11 there were 3 stacked duplexes on the Avenue side and 6 even grander simplexes. The top floor consisted of a single apartment, one of the largest and best ever designed on Fifth Avenue, it was nearly 9,000 square feet.

What evidence is there that Anna was a "showgirl"? Her parents owned a boarding house in Butte Montana where she worked. She was ambitious and bright and was able to secure more education from W.A. Clark as his "ward" when he supported her expanding her education in France sending along his sister and her 2 daughters as guardians for her. I'm a docent at Bellosguardo in Santa Barbara and the showgirl reference is not in any of the materials that we are given.

ReplyDeleteOn page 104 of the 2011 "Madams, Money, Murder and the Wild Women of Montana's Frontier," Lael Morgan details Anna Eugenia LaChapelle's talents as an actress and of Clark's financial support in her endeavor.

Delete