|

| photo by Byron Company, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

In 1868 passenger trains were forbidden by law south of 42nd

Street. The 1856 law was intended to

reduce accidents between trains and pedestrians. Therefore the three train stations—those of

the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, the New York and New Haven

Railroad, and the New York and Harlem Railroad—terminated at 42nd

Street. Visiting tourists and

businessmen disembarked 45 minutes north of the business district by streetcar.

At the time the east side of Park Avenue between 41st

and 42nd Streets was lined homes.

Realizing the need for a hotel convenient to the depots, Samuel P. Shaw

and Simeon Ford opened the Westchester Hotel at the southeast corner of 42nd

Street that year. It was an unassuming brick-faced

Italianate structure that melded well with the residences along the block.

Ford’s and Shaw’s scheme was well timed. Cornelius Vanderbilt had already begun buying

up the railroads and only a few months after the hotel opened The Sun, on

February 5, 1869, commented “Vanderbilt…wants to be considered the ‘Colloesus

[sic] of Rhodes’—that is to say, of the rail-roads.” He began buying up property between 42nd

and 48th Streets, and Lexington and Madison Avenues as he planned

his ambitious Grand Union Depot.

The name was changed at some point to Grand Central Depot and

the magnificent combined station opened in 1871—steps from the Westchester

Hotel. Ford and Shaw purchased the

adjoining property and expanded the hotel. And expanded. Later the New-York Tribune would recall “Mr.

Shaw…although not a hotel man, kept the Westchester open and from time to time

built additions to it.” Eventually the

hotel—renamed the Reunion Hotel and later the Grand Union Hotel—encompassed the

entire block.

|

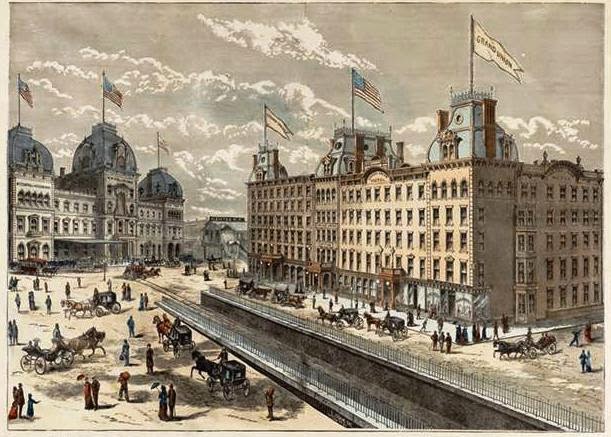

| Valentine's Manual added a non-existent mansard cap at the north end of the hotel for symmetry. The monumental Grand Central Depot is to the left. (copyright expired) |

The piece-meal growth of the Grand Union resulted in an

eccentric architectural pile. The

original building and the first addition matched. But taste in architecture moved on and the

southern annexes appeared as two mansarded pavilions flanking a central

five-story section with nothing in common with the older hotel.

Henry Collins Brown, who lived across the avenue from the

hotel recalled in 1922 “The Grand Union grew out of a row of private dwellings

that stood on the site before the opening of the depot. One by one the houses were absorbed, the

walls knocked in and the building annexed.

These various additions introduced a surprisingly numerous lot of stairs

in the most unexpected places in the hotel.”

Simeon Ford was well-known as an after dinner speaker and as

a collector of prints of sporting scenes and of old New York. Samuel P. Shaw was a collector of American

paintings. Their relationship was strengthened in 1883 when Ford married Shaw’s

daughter, Julia.

|

| Simeon Ford would manage the Grand Union Hotel for nearly half a century photo by J. E. Purdy & Co. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

Shaw and Ford famously had thrown away the entrance key the night the hotel opened. Unlike the

other Manhattan hotels, its lobby was manned and the gas lights lit throughout

the night. Henry C. Brown said “The

Grand Union Hotel was a wonderful place in its day. It was probably at its best in the early 90’s. On summer evenings they used to set chairs

out on the sidewalk, and I have counted nearly a hundred at a time. Guests used to tilt them back, smoke and chat

till midnight.”

All modern urban hotels were lit with piped gas. The innovation posed a problem when rural

guests, accustomed to blowing out kerosene lamps or candles, would do the same

with the gas jets. The result was wasted

gas or, much worse, a dead guest and the possibility of explosion. In reminiscing about the early days of the

hotel, Simeon Ford decades later related a story to a reporter.

“I remember once when a nice, benevolent-looking old

gentleman had registered and was about to go to his room I stepped up to him

and with an engaging smile, I said: ‘My dear sir, pardon me for addressing you,

but from the hayseed which still lingers lovingly in your whiskers and the

fertilizer which yet adheres to your cheap though serviceable army brogans I

hazard the guess that you are an agriculturist and unaccustomed to the rules to

be observed in one of New York’s palatial caravansaries. Permit me, therefore, to suggest that upon

retiring to your sumptuous $1 apartment you refrain from blowing out the gas,

as it’s the time-honored custom of the residents of the outlying districts, but

turn the key, thus.

“He glared at me and went his way, and I noticed that the

clerk, who had been standing by, had broken into a cold sweat.

“’Why,’ said he, ‘that man is a United States Senator from

Kansas; didn’t you notice his whiskers?’

“’It makes no difference to me whether he is a Senator or

not, ‘I replied; ‘I am no believer in class distinctions. We cannot afford to give any man a room for

$1 and have him absorb $2 worth of illuminating gas.’”

The smell of illuminating gas resulted in a much less

humorous story on February 21, 1894. At

10:00 that night a woman got off the Boston express train and checked into the

Grand Union. Giving her name as Mrs.

Jennie Miner, she was handed the key to Room 101.

Half an hour later the watchman noticed a strong odor of gas

coming from the room and used his pass key to enter. “On opening the door,” reported The Evening

World the following morning, “he found that the woman had turned on every gas

jet in the room. A three-ounce bottle

that had contained laudanum lay on the floor.”

The woman, whom The Evening World described as “a

good-looking blonde of about thirty-three years,” was taken to Bellevue

Hospital where she died.

Investigators assumed that Miner was an assumed name and it

appeared she was down on her luck. “Her

clothing indicated refinement, although it was of a fashion that prevailed many

years ago,” said the newspaper.

|

| The writing room of the Grand Union was decidedly masculine. |

A more mysterious death occurred six years later. New York Congressman Charles A. Chickering

arrived at the hotel on Sunday 11. The

New-York Tribune noted “He had always stayed there when in the city for some

time past, and was well known to the clerks and many of the guests.”

Mrs. Chickering was in Washington, so the congressman was

alone during this stay. Monday evening

was rainy and he complained that the pain of his rheumatism was “almost

unbearable.” A waiter brought his dinner

to his room that night. It was the last

time Chickering would be seen alive.

The following morning a milkman discovered the congressman’s

lifeless body on the 41st Street sidewalk. “It is thought that he either jumped or fell

from the window of his room, directly above on the fourth floor,” said the

New-York Tribune. “Mr. Chickering was

partially dressed, and had on his trousers, vest and socks, but wore no shoes,

coat or hat.”

None of Chickering’s friends or family felt he would have

taken his own life, and that it was a tragic accident. His secretary said “Mr. Chickering was

undoubtedly opening the window, when he accidentally fell to the pavement.”

The newspaper found a flaw in that theory however. “There is no means of ascertaining how he came

to get over the four foot railing of the fire escape.”

The successful hotel warranted yet another addition in

1901. That year, in March, Simeon Ford

and Samuel Shaw commissioned architect James B. Baker to design a $237,000

eight-story annex on 42nd Street.

With the addition the Grand Union Hotel was one of the largest in New

York City.

On January 27, 1902 excavation work was underway for the

subway trench below Park Avenue at 41st Street. At noon workmen attempted to dry rain-dampened

dynamite by igniting loose powder. The imprudent

idea resulted in half a ton of dynamite exploding.

Eight people were killed immediately, four others died

later, and several hundred were injured by flying glass and rocks. One of the guests of the nearby Murray Hill

hotel “had his head blown off” as reported in The Evening World later that

afternoon. At the Grand Union Hotel,

which the newspaper described as “badly wrecked,” 30-year old Nellie Lynch, a

housekeeper, and Delia Marr, the head cleaner, were fatally injured. A telephone operator, Miss Sypher, was “cut

about head and face” and “may lose sight of eyes.”

|

| Park Avenue in front of the hotel's portico is a scene of devastation -- The Evening World January 27, 1902 (copyright expired) |

P. F. Verdon was a clerk and was blown across the room and

against a wall. He received a bad scalp

wound. Among the injured guests were

Jefferson J. Stanton whose face and hands were cut, Benjamin R. Stark of Jersey

City who was cut by glass and suffered a broken right arm, and William Thompson

who was cut.

Only a week later, on February 6, another explosion occurred. At around 11:30 in the morning excavators

triggered a dynamite charge that sent large rocks hurtling through the

air. “All minds reverted to the terrific

explosion of Monday week, and it was thought that something like it had occurred,

when innumerable pieces of rock came down on the sidewalks and pavements and

struck the Grand Union Hotel. Horses

attached to vehicles reared, and their drivers had trouble in quieting them.”

A pedestrian, Albert J. Brockley, was passing the hotel when

a one-pound rock struck him on the ankle.

Another rock, this one 50-pounds, smashed through the opening of a hotel

window that had not yet been replaced from the last explosion.

|

| A postcard reveals the several sections--the original two at the near corner, the next buildings with their mansard caps to the south, and the 1901 addition at the far left. |

In the spring of 1905 22-year old Anna Bennett was working

at the Grand Union Hotel at the telephone switchboard. She earned a respectable salary of between $8

and $10 a week—about $250 today. But

things were about to change for Anna Bennett.

E. R. Whitney, called by The Evening World “the aged

Canadian millionaire,” checked into the hotel and was smitten with the

telephone “central.” Before long she

resigned her job. “She left her position at the hotel after the simple

announcement that she intended to be married.”

|

| Anna Bennett went from a modest living to that of a wealthy socialite. The Evening World September 9, 1905 (copyright expired) |

It was Whitney who spilled the beans and set society on its

ear. When he was asked if he truly

intended to marry the working girl, he replied “Indeed I am to be married and

to one of the prettiest and sweetest women in the world. It is a case of love and not of money. She took me for what I was long before she

knew I had more than enough to take care of the two of us.”

The Evening World said the engagement was “on everybody’s

tongue,” not only because of the difference in their social statuses; but because

Anna was 22 and her husband-to-be “had lived his threescore and ten.”

The couple was married on Sunday afternoon May 7. “As a marriage settlement Mr. Whitney agave

his bride $100,000, and in addition to that $15,000 for her trousseau. A check for $500 and a diamond sunburst were

her wedding tokens,” said The Evening World.

The couple returned to New York after their honeymoon and took

apartments at the Hotel Majestic “until a magnificent home which Mr. Whitney

planned could be erected in Riverside Drive.”

But early in July the elderly millionaire was taken ill at

the hotel. Anna took her ailing husband

to the White Mountains to recuperate; but it was not to be. E. R. Whitney died there during the first

week of September; only four months after the wedding. The Evening World ran the unkind headline “Dead

Who Wed ‘Hello' Girl” and said that Anna Bennett Whitney “who only a few months

ago was a telephone ‘central’ at the Grand Union Hotel…has to-day a dower right

at least in an estate variously estimated to be worth from $15,000,000 to

$20,000,00.”

The year 1909 was a dismal one for the Grand Union. In February First Lieutenant John J. Moller, a

infantry officer on furlough, checked in.

“He was quiet and almost unnoticed, and made no acquaintances during his

few days’ stay at the hotel,” said the New-York Tribune on February 23. On the night of February 22 he shot himself

in the right temple in his room.

He left a letter to the Army Chaplain E. B. Smith asking “Please

pay my hotel bill and have my trunks and baggage sent to Governor’s Island, to

await instructions from my mother. My

mother will pay you for the expenses.”

He was quite detailed in his instructions, including “The black trunk

contains my uniforms. My civilian dress

is in the trunk in my room. Thanking you

for your trouble, I remain, yours truly, J. J. Moller.”

An equally gruesome scene would play out on September 13

that year when wealthy John W. Castles severed his jugular vein with a single

razor stroke. The 51-year old was president

of the Union Trust Company. He and his

family lived at No. 540 Park Avenue and maintained a country home in

Morristown, New Jersey. He checked into

the Grand Union for the sole purpose of committing suicide.

|

| The hotel looked none the worse for wear in 1914. In the background is the new Grand Central Terminal. photo from the collection of the New York Public Library |

In 1913 Simeon Ford was still managing the Grand Union Hotel

after 45 years. That year rumors began

circulating that the hotel was about to

be demolished. The building had been on

the market for $4 million and on January 25 The Sun reported that it was under

contract of sale. “It was said that the

building would be torn down and a tall structure erected which with the site

would represent $7,000,000.”

The Sun’s report was a little premature. On May 2, 1914 the hotel was closed. Interestingly, the often-repeated story that

the Grand Union Hotel was never locked was apparently true. The New York Tribune reported “No key was to

be found on the night of the closing and Simeon Ford said he never remembered having

one made.”

|

| In 1916 nothing remained of the venerable hotel. photo by Pierre P. Pullis and G. W. Pullis from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

Within two years the hotel was gone. But the site would sit vacant until 1920. Then on Wednesday, May 26 at

noon, the property was sold at auction by the City of New York. Where the Grand Union Hotel had stood rose York & Sawyer’s

masterful Pershing Square Building which survives today.

|

| photo from the collection of the New York Public Library |

Loved this, thank you! Simeon Ford and Samuel Shaw are my Greatx4 and Greatx5 grandfathers respectively, so it was nice to read of their long lost NYC landmark!

ReplyDeleteI would love to share a story with you about your decent. How can I reach you?

DeleteDoes anyone remember the Gallants that managed the Grand Union Hotel somewhere around late 1920's That's my family

ReplyDeleteInteresting story. Probably hotels like that are not possible today.

ReplyDeleteThe story of Grand Union Hotel could turn into a book. Such a hotel was unique in many ways, with all the art work involved.

ReplyDeleteI just would like to say that art and hotels have something to do to each other.Anybody would like to say about that?

ReplyDeleteI love the stories about old New York City hotels. We've lost so many of them. Imagine if the old Waldorf-Astoria, Astor, Claridge, The Drake, The Ambassador, The Biltmore, and The Savoy across from The Plaza on Fifth Avenue were saved. Their loss is as bad as the Singer Building and the original Penn Station being demolished in the early 1960's.

ReplyDelete