|

| photo by Nicolas Lemery Nantel / salokin.com |

But on December 12, 1901 the Pennsylvania Railroad made an

announcement that would change the area forever. The company planned to spent $150 million to

join New Jersey and Manhattan with an under-river railroad tunnel terminating

in a monumental station facing engulfing Seventh to Eighth Avenues from 31st

Street to 33rd Streets—the Pennsylvania Station.

Developers were quick to recognize the potential in the

surrounding blocks—soon to be swarming with businessmen and tourists coming and

going from the station. Within the year

ground was broken for R. H. Macy’s enormous department store facing 34th

Street, far above the established shopping district, and brothers James and

David Todd laid plans for upscale hotels.

At the time of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s announcement the

Doherty brothers, John and William, lived in the house at No. 488 Seventh

Avenue. William was an architect and

John earned a living as a mason. The

Dohertys would soon be moving out.

James and David Todd engaged architect Harry B.Mulliken to

design the Aberdeen Hotel at No. 17 West 32nd Street. Ground was broken in 1902, the same year that

Mulliken teamed with Edgar J. Moeller to form the partnership of Mulliken &

Moeller. Perhaps that firm’s firm

commission was also for the Todds—another hotel nearby on the side of the

Doherty house and its neighbors at the corner of Seventh Avenue and 36th

Street—the Hotel York.

Completed in 1903 the Hotel York was a standout. A two story base of rusticated limestone was

topped by a third floor of planar stone.

Above this nine stories of red brick and limestone erupted skyward in a

profusion of turn-of-the-century architectural ostentation. A residential wedding cake, the Beaux Arts façade

was frosted with carved urns, garlands, cartouches, and grotesques. Balconies of carved stone or cast iron broke

the flat planes

|

| The facade boiled over with carved ornamentation. photo by Nicolas Lemery Nantel / salokin.com |

The Hotel York opened as both a transient and residential

hotel. The lavish public spaces mimicked

the exterior with gushing molded plaster festoons and scrollwork, marble

columns and expensive carpeting and draperies.

Guests and residents enjoyed amenities like the in-house barber shop. The hotel’s proximity to the theater district

made it an immediate favorite with the acting profession.

|

| The elaborate public rooms were often the scene of formal functions -- photo by Byron Company, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York http://collections.mcny.org/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult_VPage&VBID=24UAYWT1G765&SMLS=1&RW=1280&RH=915 |

Among the first of these was well-known actor E. M. Holland. In February 1904 the 56-year old was much

annoyed with hotel security. He lived in

room 455 on the 10th floor on and February 7 went to bed with his

door open. According to The Sun the

following day, “When he woke up his overcoat, a derby hat and $17 in money were

gone.”

|

| Holland dressed for his part as Eben Holden in 1901 -- copyright expired |

The newspaper noted that “Holland was pretty sore over his

loss.” His professional pride was

perhaps bruised since, at the time, he was playing the great detective Bedford

in the play Raffles.

Also living in the hotel at the time were, according to The Sun, “Mrs. Nellie Stevens, an

actress out of a job, and her friend, a Miss Goodrich, an actress in better

luck.” In November that year the two

women met at the Liberty Theatre to see a play.

Nellie Stevens was running late and tossed her rings into a

handkerchief, hoping to save time by putting them on in the hansom cab.

No sooner had she settled into her seat in the theater than

she noticed one of her rings—a diamond valued at $400 (about $10,000 today) was

missing. She rushed back to the York Hotel

and notified the house detective Andrew Hanley.

He traced the cab back to Sullivan’s Stables on West 35th

Street; only to find out that in the day or two it took him to track it down

the cabbie, James Lawrence, had been laid off.

When Lawrence arrived back at the stables on November 14 to pick up his

pay the detective was notified. He

and Mrs. Stevens rushed the one-block distance to confront him. Lawrence admitted to finding the ring, stuck

his hand in his pocket and announced “And here it is.”

“Mrs. Stevens, with a little shriek of joy and gratitude,

seized the ring. She looked at it. Then she shrieked again.," said The Sun.

It wasn’t her ring. “This

is a phony diamond. The ring is a

ringer, and a poor ringer at that,” she exclaimed. She pressed charges of grand larceny against

cabbie with grand larceny. But she was

out a diamond ring, nevertheless.

Another actress to cross the threshold of the Hotel York was

the young and beautiful Evelyn Nesbit.

She had been married to millionaire Harry Kendall Thaw in 1904; however

she carried on a dalliance with architect Stanford White. The affair would end with the renowned

architect dead on the floor of his magnificent Madison Square Garden on June

25, 1906, the victim of an enraged husband.

During the murder trial, White’s chauffeur testified to

driving Evelyn here and there on certain occasions, including one night in

September 1905 when he dropped her off at the Hotel York.

|

| A long, permanent marquee sheltered arriving guests from the elements -- photo by Irving Underhill, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York http://collections.mcny.org/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult_VPage&VBID=24UAYWT1G765&SMLS=1&RW=1280&RH=915 |

On October 26, 1907 the new Italian conductor of the

Metropolitan Opera House arrived from Europe and moved into his apartments in

the hotel. The famed conductor would be

in friendly surroundings—the Hotel York was a favorite home for many of the

opera house’s singers and workers.

Not all the residents, of course, were in the theater. Mining engineer Thomas R. Marshall lived here

in 1907, and earlier that year the hotel had been forced into the awkward

situation of evicting a Duke.

In 1904, a day or two following his brother James B. Duke’s

wedding, tobacco millionaire Brodie Duke went on a binge of drinking and

partying. The spree lasted for several

days and along for the ride much of the time was Alice Webb, whose reputation

was not altogether without stain. On

December 19, 1904 the pair was married in the Madison Square Presbyterian

Church—although Brodie later denied remembering any of it.

Duke won a divorce decree on March 27, 1906 and a year later

Alice was living in the York Hotel. But

on May 2, 1907 the hotel was forced to evict the 38-year old for failing to pay

her board. On Saturday night, two days

later, around 9:30 she showed up at the hotel drunk “and was unable to take

care of herself,” according to the New-York Tribune. “She rejected an offer of the clerk who

wished to show her to a room, to protect her, and she left the hotel.”

While the Duke name was normally engraved on invitations to the balls

and dinners at the highest levels of Manhattan society; that night it would be

written in the ledger of the West 38th Street police station. Alice Duke was arrested around midnight

incapacitated with drink. “The woman was

well dressed. She wore a big straw hat

and big pearl earrings,” said the Tribune.

She had with her “numerous bonds and several thousand dollars of stock

of the American Tobacco Company.”

The following year on December 1 the Todds sold the Hotel York

to Columbia University professor William M. Sloane for $825,000—a substantial

$20 million in today’s dollars. Seven

days later Sloane resold the property to the Stanworth Company of which Sloane

was a director.

The English actress Maud Odell, known in the theatrical

world as “The $10,000 English beauty,” was staying in the York while playing at

the American Theatre in November 1909.

She was terrified when she received a letter threatening to disfigure

her face with acid.

“If you do not pay Mr. Mudd $100 on Wednesday following your

matinee performance do not be surprised to be shot during your next performance

or to have your face marred by acid. A

man will come up to you and say, ‘Have you a package for Mr. Mudd?’ Then you are to turn over to him a package

containing 100 iron men. Do not notify

the cops; they will not do you any good.

You will see this insignia in your sleep.”

The unsigned letter bore a sketch of three daggers forming a

triangle above a larger dagger.

Police were notified by the theater’s agent and a few days

later the actress received a second envelope.

In it was a card with the words “La Signa Monte Secunda” and the

triangle of daggers—this time with a numeral 3 in the center.

Understandably, the Edwardian actress became hysterical. Two detectives were assigned to escort her back

and forth between the York Hotel and the theater in a taxi.

|

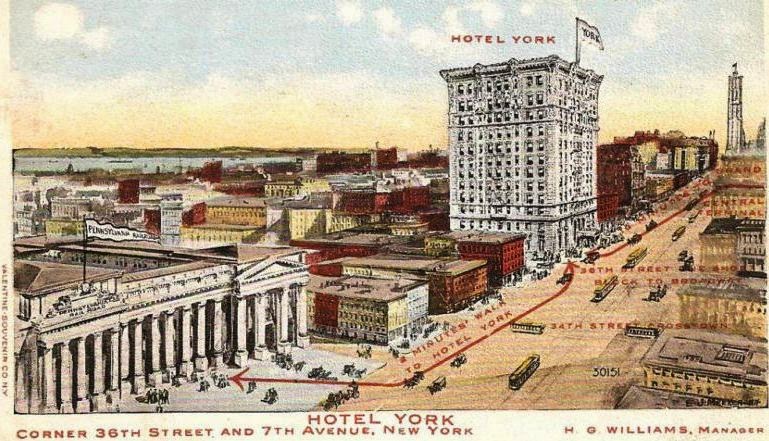

| After the completion of Pennsylvania Station in 1910, the Hotel York was quick to market its location, a "two minute walk." The hotel still soared above the neighboring buildings. |

The Italian opera singers sometimes upset the harmony of the upscale residence hotel and it all came to a head in April 1911 when singers Didur, Gilly, Pini-Corsi, and Rossi; the chorus master Romel; and the Italian conductor Signor Podesti were told to leave. Both Podesti and Didur lived in suites with their wives; the others were single. Trouble came when the conductor’s wife tried to scrimp by cooking Italian dishes in their rooms.

“The Italian singers, being of a thrifty disposition, did

not eat at the hotel, but preferred the restaurants run by their own

countrymen, where they could get macaroni and spaghetti flavored with the

grated cheese and washed down with flasks of red chianti," explained The New York Times.

That was all well and good until Signora Podesi bought a

chafing dish and, according to the newspaper, “prepared with a spoonful of butter,

a grating of full-flavored cheese, an onion, grated bread crumbs and a strong

suspicion of garlic, suppers for herself and spouse. The odor of this dish spread along the

corridor, it is said, to the rooms occupied by a learned professor from

Chicago. He protested that the perfume

of the onion disturbed him.”

Hotel management informed the conductor that cooking in the

rooms was forbidden. Repeatedly. Each time Signor Podesti would bow and

apologize and his wife would go on cooking.

It ended with everyone associated with the Metropolitan Opera Company

receiving letters of eviction.

Podesti and his wife, carrying her Pekingese toy dog Winki

under her arm, stormed into the office of the Met’s press agent. The agent was already in stress because

Caruso could not sing that night. Mrs.

Podesti lamented that they would sleep on the street and her husband waved the

eviction notice in the air.

While “the Italians held an indignation meeting around him,”

the agent phoned Jay G. Wilbraham, resident manager of the York Hotel. The agent heard of garlic and onion odors and

complaining guests; Wilbraham heard of the long-term happy relationship the Met

had with the York. In the end the troupe

was allowed to stay “if Signora Podesti stopped cooking in her room.” The tempest in the pasta pot was allayed.

Perhaps the hotel's most poignant story played out in 1922 when the

former stage star Rose Coghlan checked in to the Hotel York for the last

time. One of the best known actresses in

America for over 50 years, she reminisced about her glory days in the 1880s and

‘90s on April 7, 1922 “Lord! How fine I used to think myself with my little old

one-horse barouche and my $25-a-month coachman here in gay New York. I really felt quite grand as I drove through

Central Park and returned the bows of the society elite. I used to board the horse in a livery

stable. His name was Pete. I wonder what’s become of the poor chap.”

Now, at 70 years of age, she was penniless. Theater folk heard of her plight and sent

checks—David Belsaco’s was for $100. Telling

a reporter that she was suffering “a temporary embarrassment,” she sat in the

bed and laughed “The ‘financial whirl’ got me.

It gets the best of us, especially we women of the stage.”

The New-York Tribune described her rooms in the York as “sunny

quarters on an upper floor.” The

newspaper said “The veteran actress, suffering from a nervous breakdown, wept

as she extolled the generosity of her friends in helping her get these new and

comfortable quarters.”

After recollecting her days of stardom she cautioned “Don’t

imagine I’m repining, though. I’m

not. My friends are dear, the kindest

and best of friends. My daughter is the

dearest and most capable of daughters.

Without her I’d have been poor indeed.

Now I’m rich.” She wiped a tear

from her eye and continued, “I’m rich because the sort of folk I always wished

to have love me still do. That, I

assert, is fortune enough.”

|

| Rose Coghlan and her husband, Charles, perform in the 1894 play Lady Barter. Photograph by Byron Company, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York http://collections.mcny.org/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult_VPage&VBID=24UAYWT937VB&SMLS=1&RW=1280&RH=915 |

Rose’s daughter was there to take the aged actress to her

home on Long Island. Her mother told the

reporter “You mustn’t think I’m living in the past, though. I’m going back to the stage. In a few months with the sunlight and the

lovely outdoors I’ll be myself again. It

isn’t in me to be an invalid…In three months from now I’ll be kicking up my

heels like a schoolgirl—just like a schoolgirl—just..” And in the middle of her sentence the elderly

woman who had brought audiences to their feet for decades had fallen asleep.

In 1925 the hotel was renovated to accommodate stores at

street level. Throughout the next few

decades fewer and fewer of the theatrical crowd would live here as newer hotels

opened closer to Times Square—now the undisputed center of the theater area.

With the entertainment district gone, the Garment District

took over. By the 1960s the York Hotel

was occupied mostly by traveling salesmen.

Only two floors of the hotel were now rented for guests; the rest having

been taken over by garment salesmen as would-be showrooms, especially during

market weeks. The salesmen and buyers

who managed to get one of the rooms for sleeping would pay $15.65 for a single

with bath.

In March 1968 a young designer took room 613 in order to

market his first collection—a total of nine designs. It was Calvin Klein’s foot in the door of the

Seventh Avenue fashion industry.

|

| A modern glass marquee stretches the near-length of the first floor. photo by Nicolas Lemery Nantel / salokin.com |

In 1986 Martin Swartzman & Partners purchased the

12-story building and commissioned architect Costas Kondylis to converted it to

mixed commercial and residential space. Completed

in 1986 the former hotel opened with 108 rental apartments.

Although the street level has been brutalized with unsympathetic

storefronts and an out-of-place green glass marquee; the grand 1903 former

hotel—once home to actresses and divas—still drips with Edwardian decoration.

|

| photo by Nicolas Lemery Nantel / salokin.com |

.png)

"Modernizations" like that ground floor always make me wonder if the designer has a broken neck and can't look up to see what a travesty is being created.

ReplyDeleteA "designer" of these types of modern monstrosities doesn't care....it's all about function and cost.

DeleteWhen I was in NYC, I always wondered what kind of history has this or that building seen... Of course, there are a lot of new ones, but especially in Midtown, there are a plenty pretty old ones, most of them - hotels, like the ones you've shown. I'm now settling my next trip to NYC and I was wondering if you can recommend me some "legendary" hotel, I've already looked up Four Seasons on http://new-york.hotelscheap.org/ and it's sadly not in my league, even if I find some kind of deal.

ReplyDeleteAnother thorough and fascinating historical summary! With the recent destruction of the nearby Hotel Pennsylvania, it's amazing the York continues to survive.

ReplyDelete