Around 1853, Lewis Morris Rutherford began construction of a handsome, 29-foot-wide home at 126 East 17th Street (renumbered 237 in 1866). A wide stoop rose to the arched entranced flanked by engaged Doric columns upholding a molded entablature. The floor-to-ceiling parlor windows were fronted by a full-width cast iron balcony. The fully-framed openings wore molded cornices and sills. Although Italianate in style, the house exhibited a carry-over from the waning Greek Revival style in the squat attic windows below the exuberant cornice.

Although defaced with iron fire escapes and rooftop fencing, most of the original architectural elements survived in 1941. via the NYC Dept of Records & Information Services

Rutherford sold the newly completed house in 1856 to Margaret Ann Fish Neilson, a relative of his wife, Margaret Stuyvesant Chandler. According to her son-in-law, Maitland Armstrong in his 1920 Day Before Yesterday, the house "cost over fifty thousand dollars." If his memory was correct, Margaret paid the equivalent of about $1.6 million by 2022 standards.

Born on February 11, 1807, Margaret was the daughter of Nicholas Fish and Elizabeth Stuyvesant, both of whom came from old and prominent families. Nicholas Fish had been appointed Adjutant General of New York State following the Revolution, and Elizabeth Stuyvesant was a direct descendant of the Dutch director-general of New Netherland, Petrus Stuyvesant.

Margaret's husband, Dr. John Neilson, had died on September 22, 1851 at the age of 52. The couple had six children, Mary Noel, Nicholas Fish, Margaret A., John Jr., Julia K., and Helen. The neighborhood was filled with Stuyvesant and Fish families, and Margaret's brother, Hamilton Fish, lived steps away at the corner of East 17th Street and Second Avenue.

Moving in with her was son John Jr., a real estate agent, and her unmarried daughters. (Nicholas Fish Neilson had died in 1855 at the age of 23.) Julia married Robert Peabody Barry in the parlor in 1865, and Helen's wedding to Maitland Armstrong was held here on December 6 the following year.

The Armstrongs moved elsewhere, but Julia and her husband stayed on in the East 17th Street house. Little by little the population of Margaret's home increased. Herbert Barry was born in 1867, and Lewis Peabody came along the following year. Sadly, the parlor where his parents were married was the scene of Lewis's funeral on August 14, 1870. The little boy was just 14 months old. Julia was pregnant at the time, and three months later a third child, John Neilson, was born.

Although she retained possession of it, Margaret and her family left the East 17th Street house around 1874. It was being leased to a Mrs. Shook in 1875 as a high-end boarding house. Among the tenants in 1878 were Philo E. Doolittle, a dry goods merchant, his wife, the former Elizabeth Marks, and his mother and step-father, Caroline D. and Charles Wilson. It was not a peaceful coexistence.

On July 14, 1878, The New York Times reported, "A singular spectacle was witnessed yesterday in the Fifty-seventh-Street Police Court. At the bar stood a very respectable-looking and well-dressed man, a septuagenarian, and close by him stood his wife, his step-son, and his step-daughter-in-law." The elderly man was Charles Wilson and he faced charges of having threatened the life of Elizabeth Doolittle. The article pointed out that all four lived in the same household, but Wilson, "has incurred the enmity of his family and relatives by his extraordinary rash conduct at times."

Justice Kilbreth pointed to Elizabeth Doolittle and said to Wilson, "This lady says that you were about to strike her with a large iron poker when prevented by her husband, and that you also had in your possession a loaded cane. What have you to say?"

Wilson said, "All I have to say is that if she says so she lies."

He then explained that on that morning his wife was in the rear yard and called for the servant girl, who was upstairs. She did not respond. Caroline Wilson called repeatedly, with no answer. And so, Wilson stormed upstairs and berated the girl. "You heard my wife call you, why did you not answer?" Wilson continued, "She said nothing, and I told her that if she did not answer my wife the next time she was called I would jerk her liver out. This woman here, Mrs. Doolittle, then interfered, but what she said about me threatening to take her life with a poker is an utter falsehood. We had a few words but that is all."

Unfortunately for Wilson, his step-son, his wife, and the arresting officer all testified that he had had a poker. He was sent to Blackwell's Island for six months. Despite the tensions, the extended family was still here a year later.

Margaret Fish Neilson died on March 3, 1877 at the age of 70. The East 17th Street house was inherited in equal parts by her children. (In April 1882, Julia K. Barry, who now lived with her family in Warrentown, Virginia, sold her portion to her sister Margaret, for $5,500, about $150,000 in 2022.) The siblings continued to lease the house, which was still being operated as a fashionable boarding house.

Among the residents in the mid-1880's were Lt. Butler Coles and his wife. Born in 1831, he came from a military family. His grandfather was General Nathaniel Coles, and his father was Major General Nathaniel Coles. During the Civil War, Butler Coles had served three months at Harper's Ferry, and was later captured, spending seven months at Libby Prison. There he contracted "infirmities from which he never fully recovered," according to the Huntington Long Islander. He was now associated with Tweedy & Co., a hat manufacturing firm.

Coloratura soprano Annie Louise Tanner lived here in 1891. Her husband, Wells B. Tanner had died in 1885. Said to have a vocal range of three octaves, she had been a member of the Ovide Musin Concert Company since 1888. The Geneva Advertiser said possessed "so phenomenal a range for a soprano voice to be styled the 'American Nightingale.'"

The East 17th Street house was the scene of what The Geneva Advertiser called "a wedding of music" on October 7, 1891. Annie Louise Tanner was married to her employer, violinist Ovide Musin. The virtuoso groom had been awarded first prize for violin at the Royal Conservatory of Liège, Belgium when he was just 11 years old. The couple would perform together for years, touring world-wide.

In April 1900, Margaret Neilson's heirs sold 237 East 17th Street. Again a single-family residence, it became home to Lewis Henry Morgan and his wife, Camilla Leonard. The couple had two children, Henry Carey, who was eight years old at the time, and Camilla, who was seven. Shockingly, a year later on October 31, 1901, Morgan died in the house at the age of just 35.

Camilla briefly leased the house to former Nevada Senator John Percival Jones. He and his wife, the former Georgina Frances Sullivan, had three daughters, Alice, Georgina Frances, and Marion.

Marion had already made a name for herself outside of society teas and ballrooms. An accomplished tennis player, she won the women's single's titles at the 1899 and 1902 U. S. Championships. At the 1900 Summer Olympics, she became the first American woman to win an Olympic medal.

The Joneses announced Marion's engagement to architect and violinist Robert Farquhar in June 18, 1903. Her wedding in Grace Church took place on September 29. The Evening Telegram noted, "Several hundred guests were invited to the ceremony, which was followed by a reception at the residence of the bride's parents."

The family of banker and businessman William Fellowes Morgan, the brother of Lewis Henry Morgan, was in the East 17th Street house the following year. Coincidentally, his wife, the former Emma Leavitt, was also a tennis champion, having won the Women's National Doubles Championship in 1891. She was an accomplished golfer, as well, and "won many golf trophies," according to The New York Times later.

The couple had three children, Beatrice, William Jr., and Pauline (known as Polly). The family moved into the house just in time for Beatrice's coming out. Her debutante entertainments began with a reception at here on December 7, 1904.

Young men were slipped into adult society more quietly. On the evening of April 7, 1905, the Morgans gave "an entertainment for young girls and boys...in honor of W. Fellowes Morgan Jr.," as reported by The New York Times.

The Morgans' social status was reflected in Beatrice's marriage to Frederick S. Pruyn in St. George's Church on February 4, 1907. Calling her "the very attractive daughter of Mr. and Mrs. William Fellowes Morgan," The Argus said her wedding "will be a large and fashionable one, and the bridal procession should be one of the prettiest seen there in a long time, for Miss Morgan has chosen ten of the most charming young women of society for her bridesmaids, and her sister, Miss Pauline Morgan, as maid of honor." The reception was held in the East 17th Street house.

Immense change came in October 1909 when St. Andrew's Convalescent Hospital for Women took title to the mansion. Founded in June 1886 by the Sisters of St. John Baptist in a "pleasant house" opposite St. George's Church, it originally could accommodate 12 patients. Since 1889 it had been operating from 213 East 17th Street, and in the 1890's expanded into 211 next door.

In 1908 the facility sought to expand again. The 1919 History of Medicine in New York explained, "While the question was under consideration, the house, No. 237 East 17th street, on Stuyvesant Square, was offered to the hospital. The house, a very desirable one, needing very little alteration, the trustees after somewhat protracted negotiation acquired for $47,500." The renovations began in June 1911 with an elevator, fire escapes and a new "heating plant."

The St. Andrew's Convalescent Hospital was a sort of recuperation or rehabilitation facility for patients deemed by the Sisters as being morally fit for care. In 1915 the Directory of Social and Health Agencies described it saying, "For women, girls, and children of good character, who need care, nursing, and rest, or who are recovering from acute illness, but not ill enough to be admitted to a regular hospital. It receives promptly, with or without payment, all suitable cases." The facility could accommodate 35 patients.

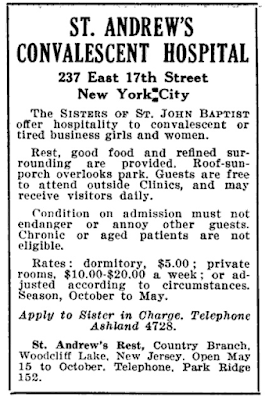

St. Andrew's Convalescent Hospital depended greatly on donations. Socialites often held benefit events, such as bridge parties, to raise funds. It appears that by the early 1940's the facility no longer offered free accommodations. An advertisement in The Living Church on January 14, 1942 noted private rooms cost $10 to $15.

After operating from the former mansion for four decades, in 1957 St. Andrew's Convalescent Hospital closed the East 17th Street facility. The building was converted to the Gramercy Park Nursing Home that year. It was most likely at this time that nearly all of the Italianate details were shaved off the facade and the brownstone was either removed or covered with a brick veneer.

The proprietor of the Gramercy Park Nursing Home, Eugene Hollander, might have been a bit nervous when he received a summons from Congress that read in part:

You are hereby commanded to appear before the Special Committee on Aging of the Senate of the Unites State, on January 21, 1975, at 10 o'clock a.m. at 270 Broadway, New York, New York...The Committee requests your appearance along with all business records relating to the operation of the above named facility from 1969 to the present.

The Committee had good reason to suspect Hollander of misdoings. On February 3, 1976, The New York Times reported, "Eugene Hollander, a major figure in the nursing-home industry here, pleaded guilty yesterday to state and Federal charges of bilking Medicaid of hundreds of thousands of dollars to pay for such personal items as paintings by Renoir, Utrillo and Mary Cassatt, and furnishing and decorating his apartment at 980 Fifth Avenue."

The scandal put an end to the Gramercy Park Nursing Home. The following year the building was converted to apartments with doctors' offices in the basement level.

Sadly "modernized," the former Neilson mansion still shows hints of its former grandeur in the surviving stoop and balcony ironwork, and in the partial enframement of the entranceway.

photographs by the author

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

Thank you so much for this interesting post! I have lived in this building since 1980 and did not know the history behind it. Really appreciate it!

ReplyDelete