In the 1870's Richard W. Buckley was deemed by the Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide to be a "rising young architect." In 1880 he formed a partnership with developer Robert McCafferty. Initially McCafferty & Buckley designed and erected rows of middle-class brownstone homes. But in the 1890's they aimed at a more moneyed customer base.

In 1900 they began construction on a row of sumptuous mansions at 18 through 26 East 82nd Street. Completed the following year, the Beaux Arts style houses were harmoniously, yet individually, designed. Like the others, 18 East 82nd Street was intended for a wealthy buyer. Five stories tall and 26-feet wide, its four-story bowed bay was crowned with a stone balustrade.

McCafferty & Buckley sold the mansion in December 1901 to William E. and Clara Tranter Reis. Reis was president of the Shenango Valley Steel Company. He and Clara moved to New York City in 1899 upon the organization of the National Steel Company, of which he was also president.

The family did not remain in the mansion especially long. They sold it on May 18, 1908 to Fannie C. Hoadley and provided the mortgage. It was a transaction the Reises would regret.

The former Fannie Curtis was the wife of Joseph H. Hoadley, described by the Times Union as "reputed to be worth $15,000,000." (That amount would be closer to $430 million today.) Hoadley was the president of the International Power Co. and the Hoadley-Knight Coal Mining Machine Company. The couple had a daughter, Grace.

They had barely moved in when Hoadley found himself in court, sued by Elizabeth C. Prall, widow of William E. Prall. Hoadley had been associated with Prall in the Prall Engine and Power Company, and Elizabeth accused him of illegally using trademarked engine designs.

Despite the Hoadleys' reputed fortune, they were slow at best at paying their mortgage. On November 12, 1910 the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that William E. Reis had filed a foreclosure suit against Fannie C. Hoadley. In what must have seemed an impertinent move, Fannie purchased the mansion at the foreclosure auction.

And it was not the last time. On February 20, 1913 The Sun reported, "Mrs. Fannie Curtis Hoadley yesterday bought in foreclosure her house at 18 East Eighty-second street for the fourth time in a year." The Reises had managed to transfer the $105,000 mortgage to the New York Life Insurance Company, so they were free from the battle.

The article explained that at a foreclosure sale a year earlier, "Mrs. Hoadley bought the house, paying 10 percent of the purchase price. She defaulted on the rest. This necessitated a resale and Mrs. Hoadley was again the buyer. She paid 10 percent, as before, and once more she failed to make further payment." The foreclosures and purchases went on, each time Fannie putting down 10 percent. "If the sales continue and she continues to be the buyer, the amount the mortgage calls for will be eventually reached and she will hold a clear title to the property," The Sun jested.

On September 25, 1913, The New York Times reported "Grace Hoadley Weds In Haste." The article said that she and Joseph Wade had obtained a marriage license two days earlier and were married on the same day in St. Ignatius Loyola Church on Park Avenue and 84th Street.

It appeared that there was tension surrounding the union. The article said "Mr. Hoadley declared last night that his daughter had married Mr. Wade with parental approval, and that he had been unable to attend the wedding ceremony on account of illness...The bridegroom's parents were also unable to be present, as they had left the day previous for Detroit, Mich."

Hoadley explained the abruptness of the wedding by saying that Grace "had made up her mind to marry suddenly as she did not care to have a large and formal wedding later in the season." A more likely explanation was the fact that Wade was a Roman Catholic and Grace was Protestant. She had been received into the Catholic faith shortly before the wedding. The New York Times noted, "According to one of the guests at the wedding, there had been some objection on the part of the bride's parents to her becoming a Catholic." But apparently the parties buried their problems and the newlyweds moved in with the Hoadleys.

Hoadley was sued by Richardson, Hill & Co. in 1914 and ordered to pay $24,653. He professed to the courts that he did not have the money. On October 15 the New-York Tribune wrote, "Hoadley lives at 18 East 82d st. He said he did not know who owned the house, as he paid no rent...The furniture in his home belongs to his wife, said Hoadley, and he has not given her any money in several years." He further stated that he had no bank account, and paid all his bills in cash. As president of the International Power Company, he received no salary, he claimed.

Notwithstanding his alleged poverty, the Hoadley's maintained an elegant yacht, the Alabama. When the mortgage company discovered the fact in 1916, it obtained a summons "directing Mrs. Hoadley to show cause why she should not be held in contempt of court for failure to pay the judgment in that she was the owner of a $9,000 yacht." Hoadley countered that "he had used the yacht in the company's business--entertaining customers."

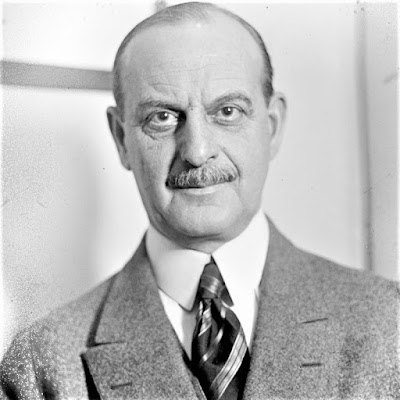

This photograph of Hoadley was taken in 1905, three years before the family moved into 18 East 82nd Street. from the collection of the Library of Congress

The couple could not scam the system forever. In March 1916 they had, for the eighth time, purchased the house in a foreclosure sale, paying 10 percent of the purchase price. But the Mutual Life Insurance Company, which held the mortgage, was losing patience.

Deputy Sheriff Katzenstein gained entrance to the house by telling the butler he had a letter for Hoadley, and then putting his foot between the open door and the jam so it could not be closed. He "gradually forced [in] despite the struggles of the servants," said The New York Times.

Katzenstein later reported "the house has two elevators, but only one of them can be seen on entering the main hall. A smaller elevator is concealed behind a specially built wall, which can be reached only by a person pressing a button and causing a panel in the wall to slide back." He said that the servants, "had tried to get him into this private car, when they found he had located it, for the purpose of imprisoning him by stopping the car between floors."

In November 1916 deputies and a private detective staked out the house for days, waiting for one of the Hoadleys to appear. The New York Times reported, "They saw Mrs. Hoadley at an upper window. Friends and acquaintances of the Hoadleys called in motor cars and entered and departed, but the officers could get no nearer to either the host or the hostess." Despite the 24-hour surveillance, Joseph and Fannie slipped away.

"Then word reached the waiting officers that Mr. and Mrs. Hoadley had gone, leaving their fine home in possession of their daughter, Mrs. Wade," reported The New York Times on November 15. Recalling the hidden elevator, Deputy Sheriff Katzenstein suggested there was a secret tunnel, as well. "I'm sure the dignified Mrs. Hoadley would not have climbed a rear fence to a neighbor's yard and departed in that way," he said.

However they escaped, officials were certain they had "reached the safe asylum of their yacht Alabama, anchored somewhere near Rye Beach, or perhaps were on the way by sea to Florida."

Eventually, the Hoadleys returned to the East 82nd Street mansion, but the pressure on them did not let up. On the night of April 13, 1919, according to Hoadley, he and Fannie were up late. Around 1 a.m. Fannie went to bed and Joseph continued reading a book. The following morning Fannie was found dead in a maid's room.

The Times Union reported, "the room was filled with gas from two open jets in the chandelier." The newspaper deflected the idea of suicide by saying, "It is believed that in attempting to turn them off when she was about to retire, she accidentally opened the cocks." It also put a positive spin on the couple's recent history. "Mrs. Hoadley, who was 42 years old, together with her husband had lived a life of real adventure...Other promoters and financiers, together with investors, have frequently been hot upon his trail. Mrs. Hoadley was a loyal and resourceful wife, and as such, could seldom escape the role of heroine."

An investigation proved the theory of accidental death wrong. On April 18, 1919 The Record of Hackensack, New Jersey quoted Dr. Benjamin Schwartz, acting chief medical examiner as saying, "I think there can be no question that Mrs. Hoadley committed suicide."

Fannie's sudden death may have been enough to distract Joseph from another foreclosure sale less than a month later, on May 15. The house was purchased by Arthur B. Westervelt who immediately started eviction proceedings. In court Hoadley asserted that Westervelt, "became the owner at the request of Mrs. Hoadley in order that the property might fall into friendly hands." The New York Times reported on June 5, "Hoadley said it was understood that his family would pay no rent." The ruse did not work.

After having lived in opulence nearly cost-free for a decade, on June 11, 1919 The Evening World reported that Joseph H. Hoadley "was formally dispossessed to-day of the residence at No. 18 East 82d Street." City Marshall Peter J. Gaffney served Hoadley the warrant as the trucks of the Encumbrance Division "drew up at the curbing" to empty the house.

Westervelt quickly sold the mansion to Ogden Haggerty Hammond, who did interior renovations in 1921. Born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1869, his brother, John Henry Hammond, Jr., was married to Emily Vanderbilt Sloane.

He and his first wife, the former Mary Picton Stevens, had three children, Mary Stevens, Millicent Vernon, and Ogden Haggerty, Jr. Despite warnings about transatlantic travel because of the war in Europe, Mary Hammond was intent on helping victims and assisting the Red Cross overseas. On May 1, 1915 she and Ogden boarded the RMS Lusitania headed to Liverpool. Six days later the luxury liner was torpedoed by a German submarine. While Ogden survived the sinking, Mary was lost.

Three years before buying the 82nd Street residence, he married Marguerite McClure Howland (known familiarly as Daisy), the widow of Dulany Howland. Hammond adopted her 11-year-old son, McClure.

Hammond had begun his career in real estate, but had become increasingly involved in civic administration. From 1918 to 1920 he had served as chairman of the New Jersey State Board of Charities and Correction. He would be treasurer of the Friends of Greece, Inc., the Bonnie Brae Farm for Boys, and the National Civil Service Reform League.

In 1925 President Calvin Coolidge appointed Hammond to be United States Ambassador to Spain. With the family abroad, 18 East 82nd Street was closed until their return in 1929.

Upon returning to New York, Hammond became vice president and a director in the First National Bank of Jersey City. The family maintained a summer home in Newport, Rhode Island.

In 1931, shortly after the family returned to New York, Millicent married Hugh McLeod Fenwick. (She would go on to follow in her father's diplomatic footsteps. She served as a United States Representative from 1975 to 1983, and was appointed by Ronald Reagan as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Agencies for Food and Agriculture in 1983.)

Ogden Hammond retired in 1950, possibly because of his failing health. The 87-year-old died in the 81st Street mansion on October 29, 1956.

Marguerite left East 81st Street not long afterward. In 1960 it was converted to apartments. There were now a doctor's office and maid's room on the ground floor, and two duplexes above. It was apparently at this time that the balustrade atop the bowed bay was removed. The bay was extended upward with a new, glaring brick bowed facade.

The ground floor space intended as a doctor's office was the Allan Stone Gallery by 1962. A collector and dealer, Stone was described by a colleague who said, "If not quite infallible, his eye allowed him to hone in on the best object in the room, whether an artist's studio, an antiques shop, or a thrift store."

In 2008 a renovation was initiated to return the mansion to a single-family home. The exterior was meticulously restored by CTA Architects P.C., a project which included removing the brick top floor addition and refabricating the balustrade and fifth floor architectural elements based on historic photos. The interior was not so gently treated, the architects in charge of that part of the project announcing a "gut renovation."

The exterior restoration earned CTA Architects P.C. the 2013 Residential Architect Design Award and the Restoration/Preservation Merit Award.

photographs by the author

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

4th paragraph after Hoadley photo: "host" for "hose". I wonder who he scammed next?

ReplyDeletethanks for catching the typo. Hoadley was a piece of work, wasn't he?

DeleteI would pass this building multiple times a week when I lived at 24-26, more than half a century ago. Thanks for the informative post!

ReplyDeleteFascinating back story of the Hoadley's, apparently expert upper crust scammers and/or grifters who successfully cheated their way through life for an unbelievably long time. That 10% buy back foreclosure scheme is true evil genius!

ReplyDelete