Real Estate Record & Guide, February 11, 1899 (copyright expired)

The street was already filling with lavish residences. West 72nd Street had been deemed a "park street" by the city, meaning that it was maintained by the Parks Department. Traffic was limited to the carriages of residents and the vehicles of tradesmen with business on the street--like coal deliverymen.

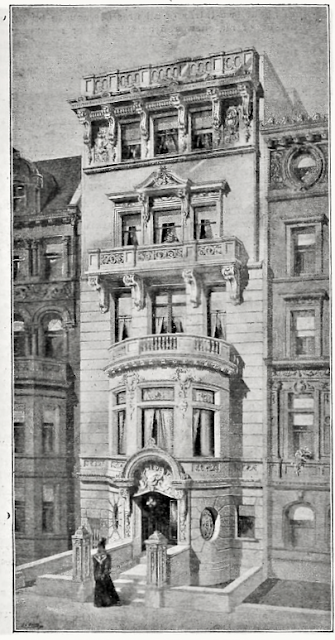

Completed early in 1899, 41 West 72nd Street fit well into the exclusive neighborhood. The Beaux-Arts style mansion was 25-feet wide and five stories tall. The Real Estate Record & Guide said it was "very carefully planned and constructed of the best materials." A short stoop led to the entrance within a centered, two-story bowed bay. The bay provided a balcony to the third floor, and another bracketed balcony with pierced railings graced the fourth. The stone cornice was crowned with a paneled parapet.

The house briefly was home to S. L. Schoonmaker, a partner in the Carnegie Steel Company. He sold it in November 1900 to Gabriel Du Val Clark and his wife, the former Josephine A. Godien.

Born in Baltimore in 1837, Clark had graduated from Princeton Univerity at the age of 17, the youngest graduate in the school's history at the time. Although he earned a law degree, he never practiced. Instead he managed his father's substantial estate and provided legal advice to his extensive businesses.

Josephine was Clark's second wife. His first, Emma Edmonson, whom he married in 1869, died in 1872. Their grown daughter, Gabrielle Edmonson Gambrill, lived in Baltimore.

Clark filled the 72nd Street house with costly furniture and decorative items. The 1912 book Baltimore, Its History and Its People said of him:

His record as a transatlantic traveler is equaled by few and excelled, perhaps, by none. No fewer than seventy times had he crossed the ocean, having made the first voyage in a sailing vessel, and during his sojourns in the art centers of Europe he had become possessed of many valuable paintings and other treasures dear to the soul of a connoisseur, trophies of travel, which were used to beautify the New York residence.

Like other wealthy passengers, when the Clarks traveled abroad they took along at least a valet and a private maid. A skeleton staff was kept on in the townhouse, but others were let go. As the couple prepared to sail in 1903 Josephine tried to aid her cook in finding a new position. Her ad read, "A lady wishes position for her cook; elderly woman; can highly recommend her."

The Clarks frequently stayed overseas for extended periods. On November 17, 1907, for instance, The New York Times announced, "Mr. and Mrs. Gabriel Du Val Clark, 41 West Seventy-second Street, have planned to spend a year in travel on the Continent. They will sail on Saturday, Jan. 4, on the steamship Hamburg."

In January 1910 Clark became ill. Perhaps hoping that the sea air would improve his condition, he and Josephine went to Atlantic City that summer. He died there on September 19 at the age of 72. In reporting his death, The New York Times mentioned, "He was an extensive traveler and had been around the world several times."

Clark's will suggests there was tension between his daughter and his wife. Josephine received the "the use of their home" for life, as well as "the pictures, plate, furniture etc." She also received the income from $200,000 in bonds held in trust. (The value of the bonds would be about $5.6 million in today's money.) The rest of the estate went to Gabrielle.

In order to make sure his daughter got her substantial inheritance, Clark added a caveat to the will. He said, "While I am confident that it will always be the desire of my wife to respect my wishes," he suggested that "unwise or evil counsel" might influence her to contest the will. Should she do that, she would forfeit everything.

Josephine lived on in the 72nd Street mansion, and resumed entertaining following her mourning period. On February 6, 1912, for instance, The New York Times reported she "will give a bridge, followed by a reception, on Monday, Feb. 12."

On the afternoon of March 26, 1913, three years after Gabriel's death, Josephine's marriage to William Vail Martin took place in the Waldorf-Astoria. Born on July 8, 1852, Martin was a director in the Lehigh and Hudson River Railway Co.

The couple entertained frequently. On January 11, 1914 The Sun reported, "Mrs. William Vail Martin of 41 West Seventy-second street will give a dansant at the St. Regis on Saturday afternoon." (A dansant was an afternoon dance during which tea was served.) And only a week later she hosted another. The New York Times reported that at that event "There were about two hundred guests, Mrs. Martin receiving in the Louis XVI suite, the dancing being held in the marble ballroom."

As she had done with Gabriel, Josephine traveled often with William. They spent the summer of 1917 at White Sulphur Springs, and the following summer season in Newport. On January 3, 1920 the New-York Tribune reported that the Martins "sail for Europe-today to remain abroad until next fall," and on September 18, 1922 the New York Herald advised, "Mr. and Mrs. William Vail Martin of New York, who spent the summer in Switzerland, have returned to Paris and are at the Hotel Ritz."

By then West 72nd Street had drastically changed. Once a restricted residential thoroughfare, its mansions were quickly being transformed to boarding houses, converted for commercial purposes, or being razed for apartment houses.

By 1925 the former Clark mansion held upscale apartments. Among the tenants was Metropolitan Opera soprano Helen Gagliasso. She was expecting a valuable package that summer--a $400 platinum wrist watch--but it never arrived. Suspicious, the she did some sleuthing.

On August 13 the Daily News reported, "The singer learned from postal authorities the watch, a gift from Milan, Italy, had been signed for at the opera house. No one there admitted knowing anything about it." Helen obtained a "John Doe summons" that "permits her to have some employee of the opera house in court Monday for questioning."

Helen Gagliasso was one of the last occupants of 41 West 72nd Street. By April 1926 it and the three houses at 43 through 47 West 72nd Street had been purchased by the newly-formed 41 West Seventy-second Street Corporation. The once-lavish homes were demolished to make way for a 16-story apartment building designed by Jacob M. Felson.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

I had never heard of a "park street" before. I guess if you're rich enough....

ReplyDeleteGuess she never got her watch?

Park Streets were rare and very exclusive. The Parks Department maintained the plantings along the curbs and such. Regarding the watch, the story seems to end there. I'm guessing it was never found, because if the crook were identified it would surely have made the news.

Delete