Real Estate Record & Guide "Office Building Supplement" June 25, 1898 (copyright expired)

The Queen Insurance Company was chartered in Liverpool, England in 1857. It had a branch in London in 1877 when it broke ground for a New York office at 37-39 Wall Street. The firm had commissioned Clinton & Pirsson (composed of Charles W. Clinton and James W. Pirrson) to design the New York headquarters. It was the first commission of up-and-coming contractor David H. King, Jr., who would go on to erect iconic structures like the Statue of Liberty and the Washington Square Arch.

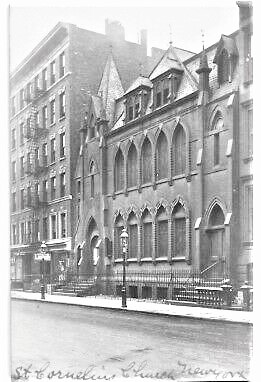

Clinton & Pirsson designed a striking six-story, Ruskinian Gothic structure faced in red brick. The top floor took the form an elaborate mansard with a pyramid-capped tower with paired arches supported by polished granite columns, and a somewhat Egyptian-shaped gable fronted by an ornate dormer.

On May 16, 1878, The New York Times applauded, "One of the most attractive buildings in Wall-street, or in the City, for that matter, is the handsome ornamented structure just completed and in part occupied by the Queen Insurance Company...Built of brick, stone, and iron, it rises six stories above a basement, and is at once substantial and ornamental."

The Record & Guide, on the same day, called the building "well deserving of special notice." The article described the colorful materials in detail, saying the granite basement was "elaborately carved" and that the:

...first story windows are of polished red granite, supported by piers of Wyoming blue stone and columns of black granite with richly carved capitals and bases of Wyoming blue stone, over which an arch is extending, covering the windows of the first story front, composed again of Wyoming blue stone and New Jersey brown stone.

Inset into the tympanum of the arch over the entrance was a bronze bust of Queen Victoria. The third through fifth floors were clad in red brick, which contrasted with the various colored stone. "The openings are arched with alternate brown and gray stone, and the jambs are finished with black and red polished granite," reported The New York Times. "The facade is elaborately carved."

The Queen Insurance Company offices occupied the bottom two floors as well as the top floor. Its offices were finished in mahogany, while the upper floors were done in maple and cherry. "The first story hall including the first flight of stairs, are wainscoted with two and three different kinds of foreign and domestic marble," said the Record & Guide. The New York Times described the fireplace in the Queen Insurance Company's Director's Room saying, "The mantel is an art study."

The top floor was used partly for document files. There were also the Queen Insurance executives' dining room, and an apartment for the janitor and his family. The New York Times commented, "From the dining-room, a superb view is obtained of the City and Bay."

The Record & Guide assured that the building was fireproof, and even the stairs were of iron. But, said the article, "in such a building very little use is made of the stairs, one of Otis's finest elevators has been provided; with a handsomely ornamented car." It ended its article saying, "The architects may well be proud of the work they have placed before the business community of New York."

An advertisement in The Evening Post in November 1880 listed the Queen Insurance Company's United States assets at $1,635,027 (about $50.3 million in 2024). The firm leased offices on the third through fifth floors to various tenants, like the banking firm of Kelley & Little; the Commercial Union Insurance Company; and law offices, like those of Hathaway & Montgomery.

The cover of a brochure featured a depiction of the building. from the collection of the New York Public Library.

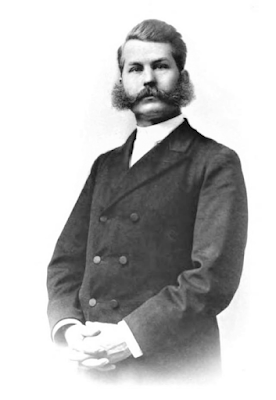

Working for the Queen Insurance Company in 1887 was W. B. Schuyler. The Sun described him as "about 28 years old, well built, and of a fine appearance." Schuyler got into some sort of trouble in the early part of 1887--serious enough to make him desperate. At 1:00 on the morning of March 4, Schuyler (who lived on Lexington Avenue) checked into the Harlem Hotel on Third Avenue at 115th Street with no bags. He did not go to work that day, but remained in the room. The Sun reported, "The maid heard him snoring, and gave up trying to wake him."

The next day, when she knocked on the door there was no answer. She informed the proprietor, who used his pass key. Schuyler was dead on the bed. On the table were two one-ounce vials labelled laudanum, an opiate popular at the time with those intending to kill themselves. A unsent letter was found addressed to Horace Maillard, which said he was in trouble, "but hoped to pull through," according to The Sun.

Three months after that tragedy, on June 18, 1887, the Record & Guide reported that the Queen Insurance Company had sold its building to the Metropolitan Trust Company for $450,000 (just under $15 million today).

When the Metropolitan Trust Company was formed in 1881, "it occupied a single room at 41 Pine street, with a force of four people," according to Trust Companies in July 1921. Within only five months its growth forced it to move to larger quarters, and in 1884 had to move again, to 35 Wall Street, next door to the Queens Insurance Company.

Although the Metropolitan Trust Company purchased 37-39 Wall Street in June 1887, the Queen Insurance Company did not vacate for nearly a year. And the timing could not have been worse for the new owners. Trust Companies recalled, "During the great blizzard of 1888, the company transferred its business to its own building next door, at 37-39 Wall street."

As its predecessor had done, the Metropolitan Trust Company leased offices in the building. Among the tenants in the 1890s were attorney Henry Daily, Jr., and the newly formed Corporation Trust Company, incorporated in 1893.

from the collection of the Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archive of the Art Institute Chicago.

On June 17, 1905, the Record & Guide printed a one-line article saying that the Metropolitan Trust Company had sold its building to William H. Chesebrough. The New York Times was more detailed, saying that the price was said to have been about $1,000,000," and that the true purchasers were "probably...Charles W. Morse and his associates." The article noted that the building, "is not likely to be disturbed for the present, but with the control of this property, it is pointed out, Mr. Morse and his associates will be in a position to erect at any time a new building."

Less than a year later, on May 20, 1906, the New-York Tribune reported that 37-39 Wall Street and its neighbor at 41 and 43 Wall Street were "being torn down to make way for a new twenty-five story skyscraper." Francis Kimball's 37 Wall Street, completed the following year, survives.

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)