Gunther was a partner in the upscale furrier C. G. Gunther's Sons. He was also the secretary of the Peru Iron & Steel Co. on Reade Street; and so, it is possible he partially influenced his architect's choice of cast iron for the building's facade. The structure, completed in 1872, was a highly sophisticated version of the commercial Second Empire style. The Aetna Iron Works had cast the iron sections. Like a wedding cake, the building's upper tiers diminished in height, visually grounding the structure. Each floor was defined by a cornice, while Corinthian columns and paneled pilasters, balconies (which originally held iron railings), and blind balustrades along the second floor gave the architecture a noble air.

Most striking, however, was Thomas's treatment of the corner. The building gently rounded the edge, with the window panes of rolled glass following the curve. Above the second floor window a scrolled pediment flanked by pedestals (that most likely once held decorative urns or finials) announced Gunther Building.

It does not appear that C. G. Gunther's Sons ever occupied the building. It quickly filled with silk importers, including Fleitmann & Co. The firm was operated by brothers Ewald and Hermann Fleitmann, with Ewald running the New York business and Hermann living and working in Germany. Also here in 1880 were silk importers Feldman & Decker, and Napoleon Godone.

Today Victorian cast iron structures like the Gunther Building are routinely painted white. But in the 19th century they were handsomely polychromed. On June 17, 1882 the Record & Guide reported that "Artmann & Fechteler, the well-known fresco painters and designers," had repainted the facade. "The prevailing colors of the Gunther Building are a deep drab and a subdued olive, relieved by the gold on the caps, cornices, brackets and columns."

By the early 1890s Hoeninghaus & Curtiss, drygoods merchants and importers of silk and ribbons, operated from 469 Broome Street. Headed by Fritz Hoeninghaus and Henry W. Curtiss, the firm (like all similar businesses) was a target for scam artists.

Early in 1894, Moses Levy purchased "a large amount of goods on from sixty to ninety day's credit," according to The Evening Post. He represented himself as the manager of his wife Julia's millinery establishment at 594 Broadway. The ribbons and other items were presumably intended as components in Julia Levy's millinery creations. Instead, said the article, as soon as the goods arrived the Levys sold them "at any price they could obtain for cash." When a representative from Hoeninghaus & Curtiss went to the Broadway shop to collect the bill on May 26, he found the Levys had cleaned it out and fled.

It did not take police long to track down the thieving couple. On May 31, The Evening Post reported, "They were arrested in Troy, and brought here from that place." The Levys had already opened two millinery shops there.

On the morning of March 28, 1899, 18-year-old Joseph Moore walked into Hoeninghaus & Curtiss with an order for $250 worth of silk from Iglick & Springer of 28 Waverley Place. Although the order was not overly large, about $8,500 in 2023 terms, a call was made to Iglick & Spring to confirm it. The decision to do so was a wise one. The Morning Telegraph reported that the call, "resulted in the arrest of Moore on the spot. It is believed that he is one of a gang which has operated successfully lately."

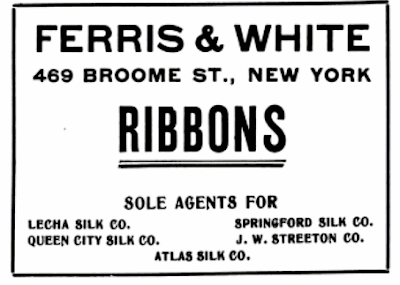

The Gunther Building continued to house silk firms into the first years of the 20th century. Among them were the Liberty Silk Works; Schefer, Schramm & Vogel; Ferris & White; and William Schroeder & Co. The latter had been founded by German-born William Schroeder. It was run in 1906 by his 26-year-old grandson, William Schroeder, Jr.

The post-World War I years saw drygoods and textile merchants joining the silk merchants in the Gunther Building. Among them were Berteaux & Radon; and Muser Bros., which imported lace goods and embroideries.

No matter how handsome the building's facade, the conditions inside the shops were harsh, with employees working long hours in lofts that were often insufferably hot. On July 18, 1922 the New York Herald reported, "The heat and humidity, working in partnership, caused considerable suffering in New York and vicinity yesterday, and as many as could went to the beaches for relief. Five drownings and five heat prostrations were reported to police." Among the latter was Jacob Balva, who "was overcome at work at 469 Broome street."

As mid-century neared, the garment district migrated northward past 34th Street. The Gunther Building filled with a far different type of tenant. Leasing space here in 1940 was the Strand Paper Box Company, founded in 1929 by Isidor Engelsberg. His sons Sidney and Moe were partners in the firm.

On August 26, 1940 The Herald Statesman reported, "Jack Feinman, thirty...who is accused of stealing more than $1,000 worth of cloth from his employers, will appear in Manhattan Felony Court on Friday." Feinman worked for the fabric firm Cohn-Hall-Marx Company. When the company discovered a large amount of stock missing, undercover detectives were put on the case. The Herald Statesman reported, "they saw Feinman place 1,000 yards of rayon and other material in a hand truck last Thursday and deliver the lot to Sidney Engelsberg" who was waiting at the service entrance.

The article continued, "At the Engelsberg box factory...detectives said they found more than 4,000 yards of rayon alleged to have been taken previously from the Cohn-Hall-Marx offices. Police say the Engelsbergs had been using the cloth to line the boxes they manufactured." Isidor Engelsberg and his sons were arrested and charged with receiving stolen property.

The 1970s saw a metamorphosis of the Soho district as factory lofts were transformed to artist studios and stores to galleries and restaurants. In 1972 the Landmark Art Gallery opened in the building and would remain well into the 21st century.

The upper floors of the Gunther Building were converted to joint living-working quarters for artists in 1976.

The lofts where silk and textile workers toiled in sometimes oppressive conditions for a century, are now luxury residences. image via streeteasy.com

In 1988, Soho 20 Gallery joined Landmark Art Gallery in the building. And around 1998 Waterworks, founded in Connecticut in 1978, opened here. It offered high-end bathroom and kitchen materials. On May 16, 2002 David Colman wrote in The New York Times that Waterworks "has put glittering, nickel-plated bath fittings on a status with Vuitton luggage." Today clothing boutiques occupy the ground floor.

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment