In 1887 real estate developer William Nobel began construction of a row of eight high-end residences that would fill the Central Park West blockfront from 84th to 85th Street. Designed by Edward Angell, each of the four-story-and-basement homes was individual, yet they flowed together as a harmonious unit. Upon the row's completion in 1889, Colonel Richard Lathers purchased 248 Central Park West.

Although, like its neighbors, 248 Central Park West was designed in the Queen Anne style, Angell had liberally slathered it with Renaissance Revival ornamentation. The parlor level above the dog-legged stoop was heavily decorated with intricate Renaissance style carvings. A rounded bay at the second and third floors was crowned by a stone balustrade. A steep triangular gable fronted the fourth floor mansard.

Lathers was born in Ireland on Christmas Day, 1821. His parents brought him to America six months later, settling in Georgetown, South Carolina. He was sent north to Huntington, Long Island to attend school. He would subsequently found the Great Western Insurance Company, a commission business, and become highly involved in railroads. In 1846 he married Abby Pitman Thurston, whose wealthy family lived on Bond Street in Manhattan and in Newport, Rhode Island. The couple would have eight children.

Richard and Abby the year of their wedding. Biographical Sketch of Colonel Richard Lathers, 1902 (copyright expired)

Lathers had been made a colonel of the 31st Regiment of the State of South Carolina in 1841. But as tensions between the North and South developed, his sympathies were decidedly with the Union. Lathers traveled throughout the South making impassioned speeches against war. On April 11, 1861 Lathers was speaking before a large assemblage in Mobile when news came by telegraph that Fort Sumter had been attacked. Lathers later said the news "brought my address to a premature end."

In 1851 he had commissioned his friend, architect Alexander Jackson Davis, to design a country home, Winyah Park, on his 300-acre estate outside the village of New Rochelle, New York. It would be only one of several Lathers family homes. Their mountain residence in the Catskills was called Chicora Cotta, and the estate in Berkshire County, Massachusetts was Abby Lodge.

The mansion at Winyah Park would be destroyed by fire on May 5, 1897. from the collection of the New Rochelle Chamber of Commerce.

The Lathers family on the lawn of Abby Lodge in the Berkshires. painting by George from Story, Biographical Sketch of Colonel Richard Lathers, 1902 (copyright expired)

The Central Park West house was filled with a fine collection of artwork and antiques. In 1902 the New-York Tribune wrote, "Mr. Lathers passes his evening of life quietly in his well-selected library, containing a fine collection of statuary, vases, rare pictures and engravings, collected during his travels in Europe." The New York Sun said, "The New York City house contains a large collection of paintings and engravings and a library of rare books, chiefly obtained in Europe."

Colonel Lathers sat at a French Empire style desk among an impressive collection of books. Biographical Sketch of Colonel Richard Lathers, 1902 (copyright expired)

The category of paintings assembled by the Lathers filled several pages. In 1896, the New-York Tribune mentioned that among the collection within the Central Park West house "may be noted original works of [Alessandro] La Volpe, Joseph Vernet, [George H.] Story, T. A. Richards, and [Alexander] Emmons, as well as Edward Moran's Centennial picture of New York Harbor, and a portrait of Colonel Lathers painted by Huntington a quarter of a century ago. There are also engravings of the works of Albert Durer (1507) Panini, Watson (1750), Le Brun, Hamilton, Bartolozzi, Turner, Simmons and Landseer."

Edward Moran's 1886 Unveiling the Statue of Liberty hung in the Lathers' Central Park West house. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

The newspaper pointed out The Lost Pleiad, "Randolph Rodger's last work, for which General Scott's daughter was the model, and 'Judith,' by Tadolini, of Rome, which was originally executed for the Italian Government, but was purchased by Colonel Lathers. A well-known Italian countess posed for this work."

Colonel Richard Lathers in 1901. Biographical Sketch of Colonel Richard Lathers, 1902 (copyright expired)

A notable entertainment was held in the house on May 23, 1892. Colonel Lathers had heard that Mary Custis Lee would be in town. He later wrote, "I determined to give a reception in her honor." Lathers invited Julia Grant, widow of Ulysses S. Grant, but because she was in mourning she sent her daughter-in-law, Ida Honore Grant. The Fredericksburg, Virginia newspaper The Free Lance-Star reported, "Miss Mary Custis Lee, daughter of the late Gen. Robert E. Lee, who arrived in New York from a short sojourn in Bermuda, was Monday night given a charming reception at the residence of Col. Richard Lathers, No. 248 Central Park west...Mrs. Frederick D. Grant was present and completed the graceful ceremony by greeting the daughter of the great soldier of the South in the name of the great soldier of the North."

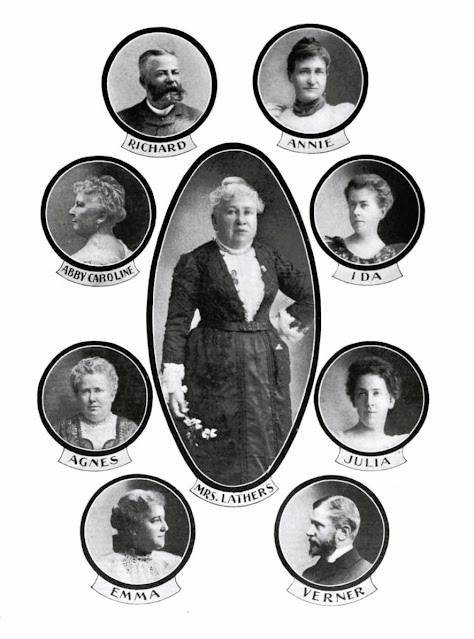

Abby Lathers and her children in 1902. Biographical Sketch of Colonel Richard Lathers, 1902 (copyright expired)

Richard Lathers died in the Central Park house on September 17, 1903 at the age of 84. Calling him "one of the most prominent southerners of this city," the Evening Star noted, "Colonel Lathers had been in feeble health for months." His body was taken to Winyah Park where his funeral was held, and he was buried in Trinity Churchyard in New Rochelle.

Five months later, on February 9, 1904, Abby Pitman Thurston Lathers died in the house. Her estate sold the residence in May 1906 to Dr. Max K. R. Reich.

A citizen of Berlin, Reich practiced medicine from the house until around 1908 when he returned to Germany and leased it to Wolfgang Gustav Triest. Like his landlord, Triest was a native of Germany, although by now had become an American citizen. A civil engineer and member of the firm Snare & Triest, he and his wife, the former Lillie P. MacDonald, had a son, Kenneth.

In 1914 Kenneth entered Princeton University. Intensely proud of his German heritage, the freshman was deeply troubled by the war in Europe.

He communicated with his parents regularly until New Year's Day 1915, when he disappeared. The college notified the Triests, and a search was launched. The New York Times reported that when no trace of the young man was found, "fearful that some misfortune had overtaken the boy, Mr. Triest employed the Burns Detective Agency to search for him."

It would be months before any clue was found. Wolfgang Triest received a letter from a former roommate of Kenneth, saying the young man had "gone to England and had enlisted in the navy there." Triest contacted the State Department and even went to Washington personally. He told The New York Times that his son "had performed a foolish boy's trick, and, being still a minor, might be discharged from the navy and returned to me at my request." He was about to discover things were worse than he could imagine.

The State Department notified Triest that Kenneth had been arrested in Britain in January and was to be tried as a spy for Germany. As Triest scrambled to get evidence to free his son, the British Government agreed to postpone the trial. Lillie Triest told a journalist from The New York Times tearfully, "Kenneth had Germany on the brain. He was trying to get to Germany. I know he was, and he thought he could do it by joining the English Navy...Doesn't it prove my poor boy's mind had given out under the great excitement of this war?"

The stakes could not have been higher. If Triest failed to get Kenneth released, he would almost unquestionably be executed. When Wolfgang Gustav Triest sailed to London in November, he was armed with letters from high-powered American officials and affidavits from Kenneth's Princeton classmates. The most significant of the letters came from Theodore Roosevelt. On November 29, 1915, The New York Times ran the headline, "Triest Lands Here, Saved by Roosevelt."

Triest took his impetuous son directly to Oyster Bay to see Roosevelt. In his letter to the British Government, Roosevelt had instructed that should Kenneth be released, his father "should bring him to me and give me the opportunity to explain to him in the presence of his father...the terrible character of the offense he has committed and the heavy load of obligation he and his family are under to the British Government."

The war resulted in yet another missing person the following year. On May 28, 1916, The New York Times reported, "Dr. Max K. R. Reich, who, if living, is easing the sufferings of the wounded on one of the battlefields in Europe, is in danger of losing his interest in the property at 248 Central Park West." Reich had not been heard from since November 1915. The mortgage payments on the house had not been paid since then. He was never found, and the residence was sold in foreclosure to Mary E. A. Wendel as an investment. (Somewhat coincidentally, her niece, Rebecca Wendel Swope, lived next door at 249 Central Park West.)

Mary Wendel leased the house to Frederick Cunliffe-Owen and his wife Countess Marguerite Cunliffe-Owen. Born in London, Cunliffe-Owen had been with the British Diplomatic Service when he and his wife arrived in the United States in 1885 "on a secret diplomatic mission which mysteriously failed," according to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle later.

A writer and journalist, Cunlifee-Owen joined the staff of the New-York Tribune, eventually becoming its society editor, writing under the name of Marquise de Fontenoy. He also wrote feature articles for The New York Times. His wife was born Marguerite de Godart, Countess du Planty et de Sourdis in Brittany in 1859. She, too, wrote, either anonymously or under the penname La Marquise de Fontenoy. Most of her books dealt with the royal courts of Europe.

Frederick Cunliffe-Owen died in the Central Park West house on June 30, 1926 at the age of 72. The emotional impact on Marguerite was intense. When she died of myocarditis a year later, on August 28, 1927, The Gazette said, "she had never recovered from the shock of the death of her husband, Frederick Cunliffe-Owen, a year ago. She had never left the house since his death and had been seriously ill for six weeks."

Mary E. A. Wendel died in 1929. She left 248 Central Park West to William Lopez Dias, who had managed real estate properties for her and her late brother, John G. Wendel, for decades. He leased the house for nearly a decade before selling it in 1937.

After mid-century it appears that rooms were being rented in the mansion. Among the residents in 1956, according to the Journal of the American Musicological Society, was Spanish guitarist Andres Segovia.

Those rented rooms caused upheaval along upscale Central Park West in the last decade of the 20th century. The New York Times wrote on December 13, 1990 that for three years it had been "the center of a bitter controversy in the fashionable neighborhood because rooms were rented to drug addicts." Neighbors complained of "nonstop parties, fights and a constant parade of strangers in and out of the house." A fight that broke out in April 1988 resulted in the death of a 23-year-old man.

There were 16 people living in the house at the time of the article. It had been being leased to former nightclub owner Frank Sokolowski, who lived on the second floor, since 1982. Just before 6:00 on the morning of December 12, 1990, an arsonist ignited a fire on the second floor. Firefighters said the flames "engulfed the building within ten minutes." The upper floors were heavily damaged.

When repairs were completed in 1996, 248 Central Park West was returned to a single-family home. It was purchased for $7.5 million in 2004 by Matthew and Janet Geller, who initiated a three-year renovation let by Rosenblum Architects. When the Gellers put it on the market in 2018 for $29 million it now boasted a sixth-floor penthouse, unseen from the street, six en suite bedrooms, a screening room, an elevator and a lap pool.

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment