Brothers Alexander and Thomas McBurney were partners in T. & A. McBurney at a time when the Greene Street neighborhood between Canal and Houston Streets was one of refined Federal style homes. In 1838 Alexander constructed a three-and-a-half story house at 79 Greene Street. The 25-foot-wide, brick-faced house was typical of the genteel neighborhood. Two prim dormers would have provided extra light, height and ventilation to the attic level.

As the decade closed, T. & A. McBurney was in serious financial trouble. Alexander took out two mortgages on his home and, according to legal documents, his mother Isabella loaned him sums of money over a period of years. In 1842 Alexander McBurney was gravely ill. Shortly before his death he transferred title of the Greene Street house to his mother, since he had no funds to repay her loans.

In the meantime, Thomas McBurney had filed personal bankruptcy a year earlier. Now, to help satisfy one of his creditors, he sold "his interest or estate in the dwelling house and lot, No. 79 Greene street...for a nominal sum" to Gordon Burnham, as recorded in court papers. There was no documentation that he or T. & A. McBurney ever possessed a portion of the real estate. The confusion of ownership landed mother, son, and Burnham in court.

While the legal process played out, 79 Greene Street was leased to Robert G. Nellis, who ran it as an upscale boarding house. His two tenants in 1845 were bootmaker William M. Young, whose business was on Ann Street; and George C. Dunwell, who listed his profession as "boards," meaning that he ran a lumber milling operation.

Finally, the courts ordered that the house be sold at auction on March 4, 1846. It continued to be run as a boarding house under widow Abby Kettlewell, the widow of George Kettlewell, and Susan Higgins. Their boarders were professionals. In 1853 they included John Mitchell, a partner in Mitchell Brothers gas fittings on Broadway; Henry C. Robe, a forwarder; and accountant Albert L. Winship.

In April 1861 "the three story and attic modern house No. 79 Greene street" was offered for lease. It is possibly at this time that Nicholas Betting took over its operation. The Greene Street neighborhood was in sharp decline. As affluent families moved further north, a disturbing transformation took hold. By the end of the Civil War, Greene Street would be Manhattan's most notorious red light district, lined with houses of prostitution. Betting ostensibly ran a boarding house, at least initially.

In the pre-dawn hours of October 29, 1867 a police officer named Casey saw a man "going up Spring-st. with a trunk on his back," according to the New-York Daily Tribune. Suspicious, he placed John Frandrind under arrest, then returned with other officers to investigate further. They "discovered that Nicholas Betting's house, at No. 79 Greene-st., had been forced open, and the trunk, which contained $175 worth of property, stolen." The amount would equal about $3,300 in 2023 terms. Faced with strong evidence, Frandrind pleaded guilty.

When Patrick Goff appeared as a witness before Judge Barnard in 1868, he described 79 Greene Street as "a common bawdy house." By 1871 Nicholas Betting had acquire an excise --or liquor--license. There is no evidence that he modified the house for a barroom, so he most likely presented his business as a hotel to the Excise Board. The license allowed him to sell alcoholic drinks to his patrons.

A general clean-up of the notorious street began in the 1870s, not only because of the work of indignant reformers, but because the commercial district was pushing northward into the neighborhood. New York's millinery industry was engulfing Greene Street by now. Hat maker Robert White purchased 79 Greene Street and in 1874 commissioned architect J. F. Duckworth to convert it into a commercial building.

Two years earlier, Isaac F. Duckworth had designed the magnificent 72-76 Greene Street, a cast iron "commercial palace" across the street. It is a mystery as to whether the two architects were related or actually the same person, with the "J" simply being an oft-repeated typo. Both had been listed as "carpenter/builder" prior to 1870, when they were listed as architects.

In either case, the transformation of 79 Greene Street would be a much less resplendent project. Duckworth's plans, filed in November 1874, called for raising the house one story and increasing the floor space with a rear extension. The renovations cost White the equivalent of a quarter of a million in 2023 dollars. When completed, the Italianate style structure left no hint of the Federal dwelling. Above the cast iron storefront, the the stone lintels and sills of the openings sat upon delicate brackets. The handsome cast iron cornice included a paneled frieze with rosettes, flanked by two substantial fluted brackets.

White's initial tenants reflected the incursion of the millinery district into the area. While the ground floor space was occupied by William G. Ferguson's frame shop, the upper floors were occupied by Robert White's hat manufactory; the hat shop of brothers Herman and Charles Schutter; Gore, Sparrow & Co., also hat makers; and Joseph T. Mast, dealer in "hatter's goods."

Calvin and Carlos Gore ran Gore, Sparrow & Co. with their partner David D. Sparrow. The firm had barely moved in when it was burglarized. On February 5, 1875, an announcement appeared in the New York Herald that read, "$250 will be paid and no questions asked for the return of the Go0ds taken from 79 Greene street the night of January 18. Gore, Sparrow & Co."

The following decade saw apparel manufacturers move into the building. Among the first was Julius J. Adams, a maker of ladies garments. In August 1885, he hired 15-year-old Lizzie Swenson as a sewing machine operator. The Sun wrote on September 19 that Adams explained, "the child had repeatedly importuned him for work, and that he employed her on the representation that her family was in needy circumstances."

Whether his hiring the teen was actually an act of kindness came into question on September 28, when the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that Lizzie "caused the arrest of Adams, charging him with having kissed her." In court, Lizzie testified that on September 18, when work was over, Adams sent her out to change a dollar bill. The Sun reported, "When she returned with the change another girl named Dora was waiting to accompany Lizzie home. Adams sent Dora out for a package of candy, and while waiting for Dora to return, Lizzie says Adams put his arms around her and kissed her." The embrace was apparently more aggressive than a peck on the cheek. "She struggled to get away, and with considerable difficulty did so," said the article.''

Adams, on the other hand, accused the girl of merely seeking money. When he received a note from his lawyer telling him of the charges, he "wrote an indignant reply, saying that he had not one cent for blackmail, but plenty for his defense." It is unclear who won the case, but Adams, who was not only wealthy but male, had the clear advantage.

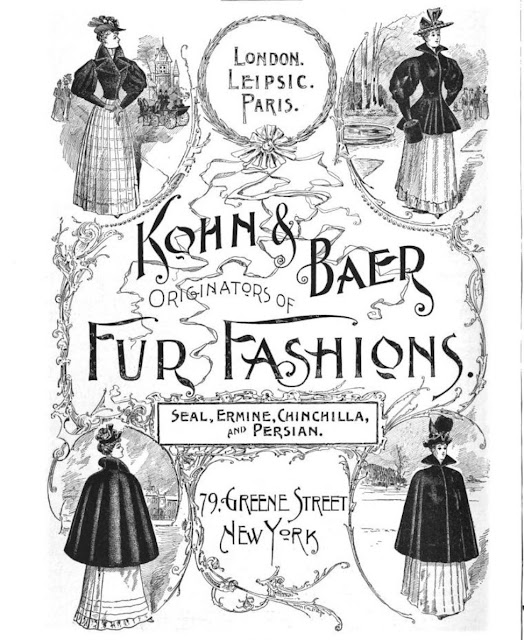

By the 1890s the building had filled with apparel firms. Davies & Wilinski, makers of cloaks and suits, was here in 1891; and by 1893 Kohn & Baer, wholesale fur manufacturers, operated from the building. The firm employed five men and two women that year, who worked 49 hours per week plus nine hours on Saturdays.

In its January 1895 issue, The Hatter & Furrier wrote, "Kohn & Baer, 79 Greene Street, are about winding up a most successful season in furs. Their goods have been distributed throughout the country, in many of the best houses." The article noted, "Kohn & Baer will make a new departure this year, going into the manufacture of cloaks and suits, as well as furs, and will have a complete line ready for January 15."

The turn of the century saw 79 Greene Street filled with apparel and dress goods dealers. In 1901 Rudinsky Bros, makers of cloaks and suits, employed 25 men and 6 women who worked 54 hours a week. Also in the building were Harris Siegel, a dealer in "dress goods and velvets;" and clothier Max Hurbich.

On the afternoon of July 15, 1902, Deputy United States Marshal McAveny walked into Hurbich's office and arrested him. The Evening World reported that he "was later arraigned...on a charge of entering into a conspiracy to smuggle diamonds." Ironically, Hurbich had just returned from Detroit, Michigan, where he testified against Louis Bush, charged with smuggling 181 unset diamonds into the country valued at nearly half a million in 2023 dollars. Hurbich's testimony helped to convict him. Now he was implicated and charged as an accomplice in the crime.

The building continued to house small apparel and related firms until just after mid-century, when the neighborhood was changing again. In 1964 a renovation resulted in the "storage and sorting of rags" on the ground floor, while the upper floors were used only for storage.

But as the century drew to an end, the neighborhood now known as SoHo saw a renaissance as artists converted lofts to studios and stores became galleries. In 1990 the first floor of 79 Greene Street became home to Florence de Dampierre Antiques, and the second floor to Dampierre & Company, which sold contemporary decorator items.

In 1995 Agnes B. Homme, a men's apparel store opened and would remain here for a decade. For about five years the ground floor was home to Kiki de Montparnasse described by Time Out New York as an "erotic luxury boutique...with a posh array of tastefully provocative contemporary lingerie." In 2022 Loewe opened its two-story boutique in the space.

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment