The Central Park West blockfront between 84th and 85th Street was lined with high-end Queen Anne style homes in 1930. Designed by Edward Angell, they had been home to wealthy and influential New Yorkers since 1889. By now, however, private residences along Central Park West were becoming increasingly rare as they were razed to make way for modern, Art Deco style apartment buildings. That year developers Earle & Calhoun demolished all but the three northern mansions, and commissioned the architectural firm of Schwartz & Gross to design a replacement building.

The architects would simultaneously design a similar structure at 55 Central Park West for the developers. Both would rise 19 stories and be designed in the cutting edge Art Deco style. The northern building took the address 241 Central Park West. Faced in beige brick, the great mass of the structure was relatively undecorated. The lower and upper floors made up for that with striking cast stone forms that have been variously described as cornstalks, calla lilies and tulips.

On September 5, 1931, The New York Sun reported, "the new Earle & Calhoun building at 241 Central Park West...is completely finished." The critic wrote:

Apartments of three to six [sic] apartments are contained in the nineteen-story structure which is decidedly modern both as to exterior and interior equipment. Platinum trimmed towers, designed apparently for the edification of the penthouse dwellers, and violet ray glass windows are just two of the innovations.

Like a set from a Fred Astaire motion picture, the sleek apartments had sunken living rooms with fireplaces. The bathrooms were "tiled in color" and principle bedrooms had connecting dressing rooms.

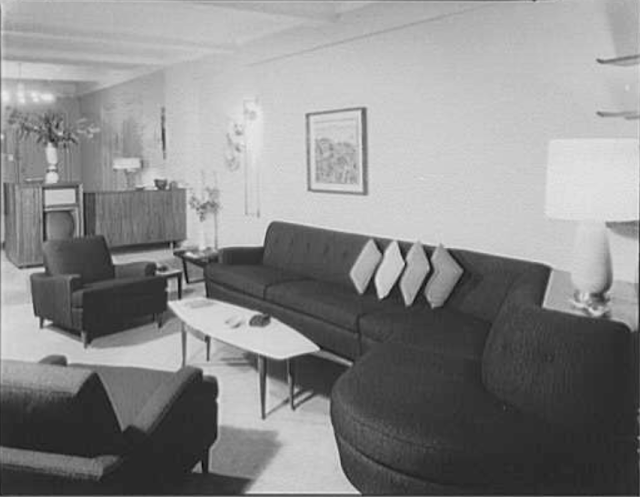

The step-down into the living room can be seen at left in this photograph of the David Hey apartment, taken in 1957. (Note that the mid-century sofa curves around the lamp table.) from the collection of the Library of Congress.

An advertisement offered apartments from three to seven rooms, noting the views "overlooking 840 acres of park. Dropped living rooms, bath to every chamber, room-size galleries, etc."

Among the initial residents were Salvatore Spitale, his wife, the former Ida Irene Firman, and their two children, Jane Helyn and Salvatore Charles. Known as "Salvy," The New York Sun described Spitale as having been a "minor character in the underworld" until the famous kidnapping of the Charles Lindbergh baby in 1932. Then he and Irving Bitz were recommended to Lindberg as "square guys" who could hunt down the kidnappers and negotiate with them. The New York Sun said, "Their employment by Col. Lindbergh put them in the police spotlight, and they have been basking uncomfortably in it ever since."

The repeated press coverage of the gangster was starkly different from the reports of the dinner parties and debutante entertainments of other residents. On June 23, 1932, The New York Sun reported, "The Brooklyn police who have been anxious to talk with Salvatore Spitale in connection with the murder of Vannie Higgins, beer runner and racketeer, reported today that their wish had been gratified."

Spitale explained that he had not been avoiding detectives, but that he and Bitz "felt it would be better, everything considered, to keep out of sight." He said, "I don't know who shot Vannie. I'd like to." He added that he had been home every evening at 241 Central Park West if they had truly tried to find him.

Ida was curt when a reporter from The Sun telephoned the apartment about the investigation. "I don't see why the newspapers are always trying to drag us into everything," she said.

And, indeed, the police were dogging Spitale. Early on the morning of June 3, 1932, three detectives headed by Alexander McKittrick raided a speakeasy, the Red Devil Restaurant at Broome and Mott Street. Spitale and Bitz were arrested on weapons charges. The New York Sun reported, "It is considered strange that McKittrick and two other detectives should walk into the Red Devil and surprise Spitale and Bitz each carrying a gun. They were stuck up so suddenly by the sleuths that they had no chance to rid themselves of their weapons."

As it turned out, the charges against Spitale were dropped in January 1933, much to the disgruntlement of police. The New York Sun reported that Police Commissioner Edward P. Mulrooney said "he is going to 'get to the bottom of the matter' and learn why a permit was given to a man with a criminal record." Spitale's attorney saw the case in a different light, telling reporters that police were "on a fishing expedition and it's about time they pulled their boat in."

Receiving more positive press was Emil E. Shauer. Born in Bohemia, he was brought to America as a child. He originally worked as a buyer of lace curtains, but his fate changed in 1905 when he partnered with Adolph Zukor and Marcus Loew in running penny arcades. In 1913 the Famous Players Company was founded to make silent movies. Shauer became assistant treasurer, and when the Paramount-Famous Players Lasky Corporation was organized, he was put in charge of all its foreign business. In 1932, Paramount International Corporation was formed and Shauer was made its vice president.

Other early residents were Edward M. and Josephine West; and William A. Earl and his wife, the former Lucretia M. Higgins.

Edward West as born in Philadelphia and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. After working as a sports reporter for The New York Times, he became a partner in the Leson Advertising Agency. He later established himself as an authority of the marketing of merchandise, co-founded the Advertising Agents Association of America, and became research executive for Sears, Roebuck & Co.

William A. Earl exemplified the affluence of the residents. An attorney and the general manager of the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Co., his passion was sailing. His yacht was the Sea Gull III and The New York Times noted that he had been "navigator on other yachts in the Block Island races, and wrote and lectured on the subject of yachting." He was vice-president of the New York Athletic Club and commodore of its yachting department.

Willard Huntington Wright and his wife Eleanor Rulapaugh were initial residents of 241 Central Park West--but the public knew them by other names, S. S. Van Dine and Claire De Lisle.

Claire was a portrait painter and S. S. Van Dine was an art critic and prolific novelist. His non-fiction writings and critiques took backstage to his detective novels when he published his 1926 The Benson Murder Case that introduced the public to fictional detective Philo Vance. By 1928 he had published two more, The Canary Murder Case and The Greene Murder Case and had become one of the best-selling authors in America.

While living at 241 Central Park West, Wright's plots were first transformed to screenplays. Of his 13 novels, 11 were made into feature films starring actors like William Powell, Basil Rathbone, Rosaline Russell and Jean Arthur.

On April 13, 1939 the Greenfield Recorder-Gazette reported, "S. S. Van Dine, the man who set the eminently clever Philo Vance sleuthing through the pages of 11 first-rate murder mysteries, is dead." The article explained, "Apparently in good health, Wright collapsed Tuesday night in his home, 241 Central Park West, and died of heart disease." He was 51 years old.

William and Ida Bloom lived here by the 1940s. Bloom operated an apparel manufacturing firm, but distinguished himself from most other garment makers by personally designing the styles. He had broken ground when he became one of the first to design women's sports clothes. So integral was he in the functioning of his firm that he had his hands, fingers and eyes insured for $500,000." The New York Sun commented that the policy "was said at the time to have been one of the largest of its type ever written."

Salvatore Spitale was not the only gangland figure to live at 241 Central Park West. While William Bloom was making women's sportswear, Robert B. Greene and his cronies operated an illegal betting operation. The New York Sun described him as a "notorious gambler."

During the 1940 election campaign, he and Max Fox placed a $300,000 bet (around $5.8 million in 2023) on Wendell L. Willkie. Unknown to Fox, just before election day Greene "hedged" on the bet, thereby saving the funds, but not telling Fox. Afterward, he hired Morris Wolen, alias Wolensky, a known gunman, as his bodyguard. His precautions did not work. Robert B. Greene and Wolen were in the White House Bridge Club on August 3, 1942 when Max Fox walked in and fatally shot them both.

Irving Mendelson had attended the University of Pennsylvania where he had "attracted wide attention in the East as a fast and comparatively small left guard" for the football team, according to The New York Sun. Upon his graduation in 1940, he moved into 241 Central Park West with his sister and her husband. When the United States entered World War II, he joined the army. On December 20, 1944 the family received word that he was missing in action.

Then, in February 1945, they received a letter. The New York Sun said, "The letter from Sergt. Mendelson came from Stalag IVB, which is believed to be near Dresden." He said that his capture by the Germans had "been an ordeal." The newspaper reported, however, that he described "life in the prison camp [as] tolerable, with some books, lectures and entertainment provided." Happily, he survived the war and lived to be 74 years old.

A colorful resident of 241 Central Park West was Arthur Kober. Born in what was the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he was brought to America at the age of 4, his family finally settling in the Bronx. He dropped out of high school during his freshman year, found a job as a stock clerk at Gimbels department store, and studied stenography.

Against all odds, he became an author and playwright, and like S. S. Van Dine, was best known for one character, Bella Gross. A young woman whose goal in life was to find a man, she and her family spoke in a rich Bronx dialect. In one instance her mother laments, "Such a nice girl can't catch a fine, steady boy who knows how to put by a dolleh? She got a good head on her...She's 10 times smott like Kitty Shapiro, and still in all Kitty, she can catch a nice boy, a docteh."

On New Year's Eve 1925, Kober married author Lillian Hellman. She later told The New York Times, "We had this crazy idea that if we'd marry on New Year's Eve, we'd remember it." The couple divorced in 1932, however they remained friends and Kober wrote the screenplay for Hellman's 1939 play The Little Foxes.

Kober developed cancer in the early 1970's. He was still living here in 1975 when he died at Lenox Hill Hospital at the age of 74.

Schwartz & Gross's looming structure is a noteworthy component of Central Park West's row of Art Deco apartment buildings. And its cast stone ornamentation continues to capture the imaginations of passersby.

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment