|

| A postcard view from the turn of the last century. Where the statue sits in Bowling Green a fountain now plays. |

A small, easily overlooked notice appeared in the Real Estate Record on October 16, 1875:

The Committee on Rooms and Fixtures of the New York Produce Exchange are prepared to receive offers of property suitable for a site for a new Exchange building. Property offered must be located south of Maiden lane, and should comprise not less than eight lots of ground.

Founded in 1861, the Produce Exchange was growing tremendously, both in the products it handled and its membership. A newspaper explained "Outside of the legitimate operations in bread-stuffs and provisions, the speculative trading of the Exchange is confined chiefly to the wheat pit" and a pamphlet boasted "It controls the export grain trade of the country, and is in every way a prominent and respected body."

It was not until April 28, 1880 that the State Legislature enacted a bill to "facilitate the erection of a new building by the New York Produce Exchange," and seven months later approved the 150-by-300-foot site at the "southwest corner of Broadway and Beaver street" extending to the northwest corner of Marketfield Street. It was a well-chosen site, facing Bowling Green park. The open swatch of green would not only afford unhindered views of the new building, but offer cooling breezes off the harbor. (One member, Isaac Honig, mentioned to the Real Estate Record in June 1882 that the current building "is open to the serious objections of bad ventilation.")

Architect George Browne Post received the commission to design the structure. He estimated the cost at $2 million--around $50.7 million today. Construction began on May 1, 1881 and would take three years to complete. In order to support the foundations of the massive structure 15,000 New England pine and spruce pilings were driven into the bedrock. And to create the vast, cavernous trading room, Post used an innovative construction technique--wrought iron framing. The Produce Exchange would be the first building in the world to combine an iron frame with masonry in its construction. The cornerstone was laid on June 6, 1882. It bore the inscription "Equity" in bronze letters.

Construction of the Produce Exchange building was a monumental project. There were 2,000 windows, 1,000 doors, 15 miles of iron girders, and 12 million bricks. It would encompass 7.5 acres of floor space.

As the building neared completion, Post's cost estimate had fallen short. On October 19, 1883 The New York Times reported that the members of the Produce Exchange would be meeting to discuss "providing funds for the completion of the new Exchange building according to the plans of the architect. One of the members thinks that about $150,000 will be wanted." As it turned out, the total cost, including land and furniture, came to $3,178,645, just under $84 million today.

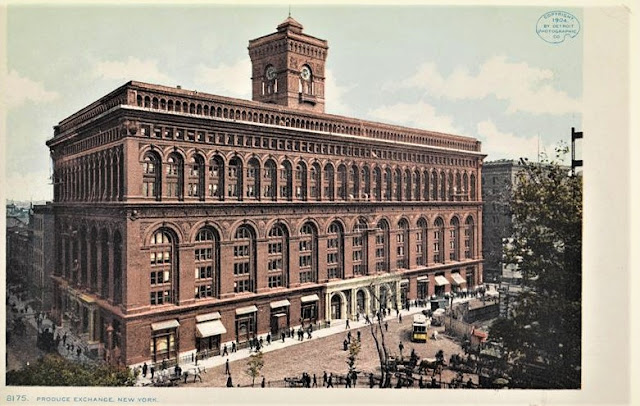

Post's commercial take on Italian Renaissance was clad in red brick and trimmed in terra cotta. The regimented tripartate design of the main structure featured rows of arched openings, those of the middle section rising four floors. Above the cornice, almost unnoticed, perched a diminutive arcade. To the rear of the structure, facing Marketfield Street, was a 225-foot tall campanile, or tower from which stunning view of the harbor and lower Manhattan could be had.

Even before the doors were opened the critic from the Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide pounced. On November 17, 1883 he described the building as a "box" which was "so long that in spite of its being nine or ten stories high, it looks squat, and then another box, very tall and narrow, is set up alongside of it. Two boxes are no less boxy than one, and the Produce Exchange, though an impressive feature in the view of lower New York by its mass, has no other impressiveness." The critic then took aim at the campanile. "With a good outline detail which is only tolerable may pass very well, while no force or grace of detail can redeem a building which has no general form."

Not every critic agreed. The Metropolitan Holiday Supplement called it a "handsome, solid structure," and said "Of the modern Renaissance in style, the general effect is imposing, and imparts the idea of strength and permanence." And if that were not praise enough, it continued, "From any standpoint the Produce Exchange is unsurpassed by any structure of its kind in the world."

|

| The still-surviving houses on the right would be razed for the New York Customs House in 1899. Harper's Weekly, July 1886 (copyright expired) |

Post's use of iron framing was not the only example of up-to-date technology. The Produce Exchange was electrically lit and had hydraulic elevators. Speaking tubes communicated with each office. The tower was illuminated at night, an early example of a practice commonplace today.

On April 10, 1884 The New York Times reported on the plans for the opening celebrations on May 6. Farewell exercises in the old building would be held at 11:00 a.m., followed by a procession to the new which would be headed by "members of the Exchange over 45 years of age." Two bands had been hired for the occasion. At 2:30 that afternoon a "steamboat excursion" in the harbor "will be one of the features of the celebration," reported The Times.

Technically, however, the Exchange would open the evening before. "It has been decided to hold a ladies' reception in the new building on the evening of Monday, May 5, upon which occasion it is expected that there will be dancing in the great board-room."

Although there were 3,000 members and each was allowed three tickets, there was little concern for overcrowding that night. The Times said "The great size of the building will undoubtedly prevent an uncomfortable crush upon this festive occasion."

Called "arena-like" by the Metropolitan Holiday Supplement, the trading room on the second floor was 220 by 144 feet and rose 60 feet to a stained glass ceiling. The largest trading space in the world, The New York Times described it on May 4, 1884:

On April 10, 1884 The New York Times reported on the plans for the opening celebrations on May 6. Farewell exercises in the old building would be held at 11:00 a.m., followed by a procession to the new which would be headed by "members of the Exchange over 45 years of age." Two bands had been hired for the occasion. At 2:30 that afternoon a "steamboat excursion" in the harbor "will be one of the features of the celebration," reported The Times.

Technically, however, the Exchange would open the evening before. "It has been decided to hold a ladies' reception in the new building on the evening of Monday, May 5, upon which occasion it is expected that there will be dancing in the great board-room."

Although there were 3,000 members and each was allowed three tickets, there was little concern for overcrowding that night. The Times said "The great size of the building will undoubtedly prevent an uncomfortable crush upon this festive occasion."

Called "arena-like" by the Metropolitan Holiday Supplement, the trading room on the second floor was 220 by 144 feet and rose 60 feet to a stained glass ceiling. The largest trading space in the world, The New York Times described it on May 4, 1884:

Its smooth, white walls are agreeably relieved by the cherry wainscoting and door casings. The huge skylight overhead is of bright colored glasses and the 23 well proportioned windows which give light and air to the apartment are in graceful harmony with both the interior and exterior decoration.

The morning after the event the newspaper wrote "As early as 7:30 o'clock it was impossible to get seats in the elevated road on the west side. Ladies and gentlemen in evening dress were crowding in at every station, and the brakemen, who were as full of ignorance as usual, were speechless with wonder. At the same time more carriages were rolling down Broadway than were ever seen on an opera night."

Eventually members settled into their new home. The trading room was a hub of activity, viewed by visitors from the "massive gallery with ornamental facing" which ran along the northern wall. Off the trading room were the library and executive offices.

Membership in the Produce Exchange was not all business with no pleasure. On the night of the building's opening the 40 members of the New-York Produce Exchange Glee Club had its own celebration with a dinner at Clark's on 23rd Street. And in July that year the Produce Exchange baseball club was organized.

Trading gave way to merriment every December 31. On January 1, 1885 The New York Times wrote "Several hundred ladies looked down from the broad gallery in the Produce Exchange upon a merry scene yesterday afternoon. The floor of the immense board room was well filled with men and boys, all of whom entered into the enjoyment of the New Year's jollification without reserve." The Seventh Regiment Band was there to play "popular airs" (including the "Produce Exchange March") after trading came to a close at 2:30. The members were entertained by an exhibition of fancy bicycle riding, "some graceful roller skating," and a tug-of-war and a sack race among the boy messengers.

|

| This turn-of-the-century postcard clearly shows the campanile with its four clocks. The janitor's apartment was in the tower. |

Members of the Exchange did not always act gentlemanly, as one would expect. In the spring of 1885 relations between two traders of opposing firms, Alpheus Geer and Archibald Montgomery, had "lately been rather strained," according to The New York Times on April 17. The newspaper reported that on the previous morning Geer entered the trading room just as Montgomery was about to make a bid.

"Pushing his way through the crowd, he finally got behind Montgomery, and just as he was raising his voice to shout out a price, Geer jammed his hat over his face." The astonished Montgomery turned to his laughing adversary, and did the same to him. It ended in a "Sullivan style" battle of fisticuffs on the trading floor.

To gauge the quality of the grain being traded, balls of dough were produced for examination. Dough balls routinely turned into missiles and repeatedly the governing board of the Produce Exchange chastised members for dough ball fights. Notices were nailed to the walls of the trading floor prohibiting the practice. But on June 19, 1885 the targets of the sticky projectiles were not fellow members.

The Times reported the following day that "Some of the members of the Produce Exchange succeeded yesterday in bringing discredit upon that organization and almost succeeded in inciting a small riot." Members of the 12th, 69th, and 71st Regiments were in Bowling Green park awaiting the arrival of two French ships. It was a hot day and the uniformed soldiers "began to show signs of impatience."

To get some air, several members of the Exchange were sitting on the second story cornice. At around 1:00 "intermittent showers of dough balls, grain, and apple cores fell from the Produce Exchange windows upon the heads of the soldiers." Despite protests from the militiamen, the barrage continued until one of them "pointed his musket up at the windows from which the annoying missiles were thrown and threatened to shoot."

More than an hour later the Exchange members were still engaging in their boyish prank. Finally the 69th Regiment broke ranks and charged the main entrance. They were stopped by a platoon of police officers. Seeing that trouble was imminent, the officer in charge sent between 20 and 30 police officers into the building to convince the brokers to "cease their insulting fusillade." Almost unbelievably, "Some of the members of the Exchange denounced the entrance of the policemen into their trading room as an unwarrantable intrusion," according to a newspaper.

Upon hearing of the matter Major Duffy of the 69th stormed into the Exchange and met with D. A. Eldridge, Chairman of the Floor Committee. Getting little satisfaction he left warning "I cannot be responsible for what my men will do if these outrages are continued."

Pressure from outside the Exchange forced the managers to rethink their cavalier response to the incident. An official apology was given and a search for the perpetrators "engaged in the dough throwing," as worded in The Times on June 23, was begun. The guilty parties were eventually named and repudiated.

The tradition of New Year's celebrations on the trading room floor continued year after year, as did the occasional fist fight and never-ending dough ball battles. The schoolboy mentality of some member resulted in a new diversion in the fall of 1889. On October 26 The Times reported "Dough tossing has reached such a stage of perfection on the Produce Exchange that improvised ball games with umbrellas or canes for bats and past puddings for balls are of hourly occurrence on the floor."

A proposal to enlarge the Produce Exchange had been made as early as 1888; but title to the adjoining property was not acquired until 1900, and construction on the enlargement not begun until 1904. It resulted in the block of Marketfield Street to the south being built upon.

|

| This plaque, still embedded in Marketfield Street, testifies to a time when the block was still open, but owned by the Exchange. photograph by, and courtesy of, Rob Clarke |

The members' attentions were turned to more serious matters following the Financial Panic of 1907. The economic depression, of course, affected trading; but it also left thousands of New Yorkers without basic needs. The Exchange ended its frivolous New Year's Eve celebrations on the floor and replaced them with events for the needy.

On December 30, 1908 The New York Times reported "The Produce Exchange will repeat this year the entertainment which it provided on New Year's Eve last year for the poor children and families of lower Manhattan." There was a band, a vaudeville show, and vocal music. But most importantly, "After the entertainment the presents will be distributed, consisting of about 1,000 baskets for boys, 1,000 baskets for girls, and 700 family baskets containing a New Year's dinner." The tradition continued at least through 1910.

World War I also brought gravity to the Exchange. Cities like New York prepared for the conceivable invasion by enemy forces. On March 30, 1917 the members elected to form a unit of the Home Defense League to cooperate with the New York Police Department. About 100 volunteers were organized and drills were held twice a week on the trading room floor. The Times noted "One of the members has offered to buy a machine gun for the unit if permission can be obtained from the city authorities."

|

| The men of the Produce Exchange in uniform on the floor. New-York Tribune, July 8, 1917 (copyright expired) |

A scare occurred on June 6, 1929 after a discarded cigarette smoldered in one of the telephone booths on the second floor before finally sparking a fire at around 10 p.m. It spread along the row of booths. William C. Riker, one of the seven night clerks who worked after trading hours noticed smoke and turned in the fire alarm. The blaze took an hour to extinguish and a part of one wall had to be ripped away. The fire's location along the row of telephones resulted in severe damage to the Exchange's communications. Squads of repairmen worked the following day to replace 159 pairs of telephone wires and 32 Western Union lines.

In the fall of 1930 talk of demolishing the old building was discussed. According to The Times on September 23, "A planning board appointed by the Exchange is now working with architects, real estate brokers and financiers to determine the best means for improving the site." Although the building was still adequate for the purposes of the Exchange, the valuable plot was a tempting inducement.

It may have been the ongoing Great Depression, however, that stalled plans. It was not until February 13, 1957 that demolition plans were announced. Uris Brothers told reporters that the razing "will be followed by construction on that site of a 30-story, 1,300,000 square foot, air-conditioned office building." Emery Roth & Sons had already completed the drawings.

|

| Emory Roth & Sons released this rendering. The New York Times February 14, 1957 |

.png)

That (peripatetic) statue in the first photo is of Abraham DePeyster.

ReplyDeleteAs is typical with far too many of your posts, this wonderfully bold magnificent structure was replaced by what could only be described as an offense on the eyes. Except for the horrible intrusion of the new 2 Broadway office bldg, now encased in a new curtain wall (no improvement), Bowling Green is surrounded by some of the most magnificent early 20th century buildings to be found anywhere in NYC. It is unfortunate that the loss of the Produce Exchange mars that unique architectural ensemble of early masonry architecture. NYarch

ReplyDeleteWhere the building stands now was my 9th great grandfather's home, Jacques Cossairt , I suppose he is rolling in his grave

ReplyDeleteI believe there's a typo: since the trading floor occupied most of the area of the building, I think it was 30,000 sf. not 3,000.

ReplyDeleteCould be, if so it came from a historic typo so rather than second-guess, I simply removed that statistic. thanks.

Delete