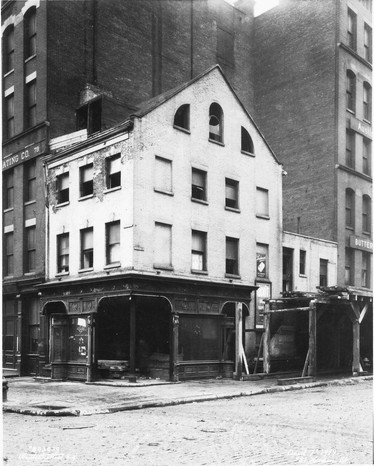

The ground floor was an outstanding example of a 19th century saloon front. photograph by Edward Loomis Davenport Seymour from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

George Harrison owned a sprawling estate on the west side of Manhattan Island in the 18th century. In 1797, two roads--Harrison Street and Hudson Street--appeared on city maps on his property. In the first half of the 19th century, houses first began appearing in the area.

One of the earliest was 1 Harrison Street at the southwest corner of Hudson Street. A substantial, three-and-a-half story building, it was faced in brick and trimmed in stone. A early example of Federal architecture, its windows on Hudson Street displayed layered keystones. The peaked attic had three windows on the Harrison Street elevation--an arched window flanked by two quarter-round openings. A double-wide dormer pierced the roof to the front.

The first occupant was "Mr. Whale," who listed himself as "Professor of Dancing." Whale operated a dancing school in the City Hotel. His four instructors included "Mr. Degville, ballet master at the Opera House in London," and "Mr. Nouvarre, principal dancer at the Grand Opera in Paris." A November 1818 advertisement said that Mr. Whale's students would learn "new Dances and a variety of Cotillion Steps, as is now danced by the fashionable circles in London and Paris." Each Tuesday, "practicing balls" were held, where young society people learned the proper steps and the accompanying, expected decorum.

On November 20, 1818, Mr. Whale announced he had "commenced at his residence No. 1 Harrison Street, corner of Hudson, for the reception of those young ladies and gentlemen who may consider his public school at the City Hotel too great a distance to attend." The classes were segregated by gender--young ladies being instructed on Mondays and Friday from 3 to 5, and gentlemen the same days from 5 until 7.

Mr. Whale staged his "grand annual ball" at the City Hotel. An announcement in The Evening Post on March 22, 1819 listed the locations where the $1 tickets could be obtained, including "Mr. Whale's residence No. 1 Harrison street, corner of Hudson street."

Mr. Whale was followed by Miss Squires in the house. On October 26, 1822, an advertisement in The Evening Post read: "Miss Squires informs her friends, that she will re-open her Seminary on Monday the 28th of October, at No. 1 Harrison street, corner of Hudson street."

By 1830, the ground floor of the house had been converted to business. The residential address remained 1 Harrison Street and the store became 81 Hudson Street. Thomas L. Jackson operated his grocery store in the space that year. John Adams ran the store from 1836 through 1841, followed by Bruce C. Smith. Smith and his family lived above the grocery store.

Henry Meyer took over the grocery around 1850. He and his family shared the upper floors with boarders. Living with the Meyers in 1853 were Patrick Crenan, a carman; Michael Garaty, a coachman; civil engineer David C. Nodwell; and Simon Strahlheim, an importer.

In 1859, Patrick Kehoe converted the long-time grocery space to a saloon. (He operated a second saloon at 322 Greenwich Street where he and his family lived.) By then, the neighborhood was bustling and the following year, on September 3, 1860, the Board of Aldermen approved the resolution "to flag and set curb and gutter stones in front of No. 81 Hudson street, and No. 1 Harrison street."

Robert G. Stevenson and Walter Taylor moved their Taylor & Stevenson saloon into the space in 1861. They were the first to list the commercial space at 81 Hudson Street. Neither of the proprietors lived upstairs. Stevenson lived at 13 Harrison Street and Taylor at 3 Harrison Street.

Stevenson also operated a produce business at 395 West Washington Market. In 1864, Benjamin Emerson, who lived upstairs at 1 Harrison Street, was also in the produce business at 395 West Washington Market, possibly a partner. That year the two men partnered in the saloon, changing its name to Stevenson & Emerson.

Most substantial saloons had rear rooms for meetings. On August 3, 1864, The Sun reported that the Dry Goods Porters and Packers, an early version of a labor union, had met here. The article said, "It was decided that it was necessary, in order to have justice done them, to organize into a permanent Protective Association."

In 1867, James Kearney took over the saloon and moved his family into the upper floors. He and his wife, Elizabeth, would eventually have three children in the house: Cornelius P., born in 1869; , Mary A., born in 1870; and Katherine, who arrived in 1871.

Sadly, Cornelius died at the age of four on February 25, 1873. His funeral was held in the house the following day.

The Kearneys were Roman Catholics and the girls attended St. Peter's Academy rather than a public school. Mary graduated in 1887, when Katherine was a junior.

Elizabeth and the girls were at Spring Valley, New York that summer. Families who could afford to spent the hot months in the country. In many cases, the fathers of the families remained in the city to attend to business, and traveled back and forth on the weekends. On the evening of July 27, 1887, James Kearney was met at the train station at Spring Valley by devastating news.

That afternoon, Mary and Katherine, who were now 17 and 16 years old respectively, "went with a party of girls of about their age to bathe at Distillery Lake," reported The Sun. The article said,

They could not swim. Mary slipped from a small raft into 15 feet of water, and her frightened sister plunged in to save her. Both girls sank together.

The screams of the other girls attracted workmen in a nearby field, but their attempts were futile. The Sun reported, "Their bodies were recovered two hours later, still locked together in their last embrace." On July 29, the newspaper reported that the teens' bodies had been brought to the city and a mass at St. Peter's Church would be held that morning after the funeral at 1 Harrison Street.

In the 1880s, the Temperance Movement began lobbying for public drinking fountains. Proponents believed that by making healthful, clean water available to the working classes, the temptations of alcohol could be thwarted. It was most likely that pressure that resulted in the Commissioners of Public Works to install a "free drinking-hydrant" at 81 Hudson Street in 1891.

By 1894, Henry Steinhardt, who also ran a saloon at 315 Bowery, had taken over Kearney's operation. In February that year, he made $2,500 in alterations to the building. The cost would translate to about $94,000 in 2025. The renovations involved the installation of a superb saloon front with four double-doored entrances with stained and wheel-cut glass. They projected away from the facade under curved metal hoods.

The neighborhood continued to change, and at the turn of the century the Hudson-Harrison Street corner sat amid the "egg and butter" district. On March 19, 1908, an auction was held "of bar and back bar, and all other goods then on said premises," at 81 Hudson Street. After having housed a saloon for nearly 80 years, the ground floor became home to the Wisconsin Condensed Milk Co.

When this photograph was taken in 1919, demolition of the venerable building had been begun. from the collection of the New York Public Library

An advertisement appeared in The Evening World on June 17, 1918 that read simply, "81 Hudson Street, Corner Harrison St. We offer this desirable corner for sale." It was purchased by Henry Mason Day, Jr. On March 1, 1919, the Record & Guide reported that he would replace it with "a new 3-story building" for his export and import food supply business. Designed by Schwartz & Gross, the terra cotta-clad Henry M. Day Building was completed within the year.

.png)

$1.00 back then is about $25 today, still a good price for a ball ticket.

ReplyDelete