photograph by Eden, Janine and Jim

In the first decade of the 20th century, apartment living had gained favor on the Upper West Side. On the opposite side of Central Park, however, things were different. Here, multi-family residential buildings were still associated with tenements--not the sort of conditions Upper East Side millionaires would consider. And so when James T. Lee (the future grandfather of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis) and Charles R. Fleischmann, partners in the Century Holding Co., acquired the plot of land at the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 81st Street in the spring of 1910, they were setting out on a risky and daring project.

Lee and Fleischman had acquired the property from millionaire August Belmont "after long negotiations," according to the Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide on June 4, 1910. Belmont had purchased the plot (which was "one of two pieces on upper 5th av. that are not covered by restrictions") as the intended site of his mansion. Now the partners conceived the third "really high-class apartment house," as described by the Guide, on Fifth Avenue.

"The house will be twelve stories high and will contain but eighteen apartments. No apartment will have less than seventeen rooms and there may be one of twenty-eight rooms," said the article. Readers were doubtlessly shocked when they read, "The rentals will range from $10,000 to $26,000, making them the highest renting apartments in the city." That shock would have been well founded. The $26,000 per year rent would translate to about $71,650 a month by 2024 conversion.

Six of the 18 apartments "will be on the duplex plan," said the article, adding,

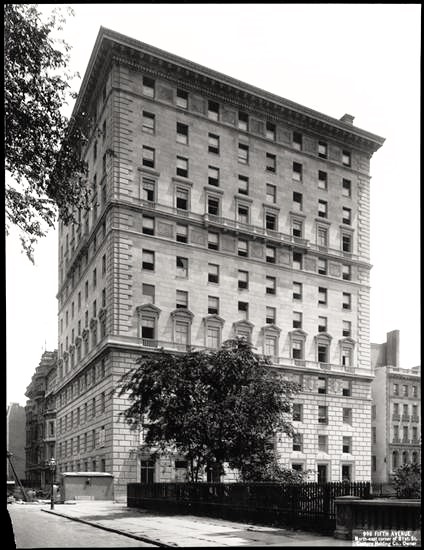

All the rooms will be of large dimensions and will be decorated as elaborately as the most sumptuous private homes. The exterior of the building will be in the Italian Renaissance, the facade being of limestone.

McKim, Mead & White, which was currently designing the north wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art almost directly across the avenue, had been given the commission. The firm's architect William Richardson headed the project. His choice of an Italian palazzo design was almost assuredly intended to slip unobtrusively into the mansion neighborhood. (McKim, Mead & White had been faced with the same consideration in 1896 when it designed the University Club within Millionaires' Row. This new building would have striking similarities.)

Richardson separated the building's three four-story sections with prominent stringcourses--one distinguished by a stone balustrade and the other by Juliette balconies. The rusticated granite base was decorated with Renaissance inspired shields. The fifth floor openings wore arched and triangular pediments, and a bracketed cornice completed the design.

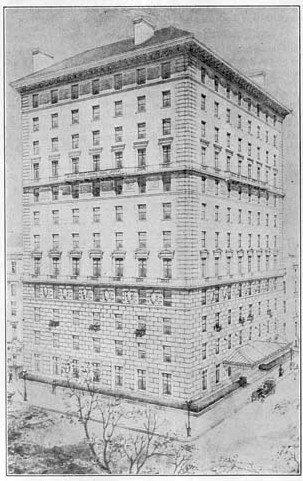

McKim, Mead & White released this rendering in 1910. Record & Guide, August 13, 1910 (copyright expired)

As excavations got underway, the Century Holding Company did significant marketing, stressing that these apartments would be commensurate to mansion living. On August 13, 1910, the Record & Guide reported, "In the plan of the house an intention is perceived to give in each apartment more and larger room than can be found in any private city dwelling, with the exception of a few of the largest residences. The four principal rooms--namely, the salon, dining-room, living-room (or library) and the gallery--aggregate 2,500 square feet."

The servants' wing was well separated from the tenants' space. The New York Times, December 7, 1913 (copyright expired)

Residents would also be supplied with jewelry safes, wine cellars in the basement, and at least six servants' rooms. As the building neared completion on March 10, 1912, The Sun noted, "the rooms have been laid out and made of such size that tenants can entertain just as they would in large dwellings. Indeed the use of fine marbles and woods in reception halls and on stairways has been so skillful that the apartments give at once the impression of expensive individual homes."

An advertisement promised, "Management provides without charge--Vacuum cleaning of suites, window cleaning, artificial refrigerator and supply of cake ice." The bathrooms were lined with marble. The Sun was impressed with the modern conveniences, pointing out,

The kitchen is provided with a waste incinerator which makes unnecessary the handling of garbage. Washing machines of the latest device and electric drying and ironing equipment are included in the service. Refrigeration is supplied to kitchens by means of a pipe coil and cake ice made on the premises as well is supplied to tenants.

At the time of the article, almost all of the apartments had been rented. Those who signed leases during construction had provided their input on the individual designs. The Sun mentioned, "In the Root and Guggenheim apartments, which include whole floors, the salons and livings rooms have been thrown together to make large spaces where receptions and dances may be held. In Senator Guggenheim's apartment this room has been done in gold, with a ceiling which probably is the equal of anything of the kind in the city."

The tenants mentioned in the article, industrialist and politician Murray Guggenheim and his wife, the former Leonie Bernheim; and Elihu Root and his wife, Clara Wales; would have equally impressive neighbors within the building. Others who signed leases during construction, according to The Sun, were Commodore Robert E. Tod, Lloyd Aspinwall, Rogers Winthrop, Levi P. Morton, Colonel George Fearing, and Henry Goldman.

On November 1, 1913, the Record & Guide concluded, "It paid to go the limit." The article said, "The highest schedule of rentals ever known in the city attracted families from the best circles of society. No more distinguished social functions have occurred anywhere this year in the city than were enjoyed in this house."

Elihu Root was a familiar name to Americans. He was appointed U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York in 1883. Then, in July 1899, he was made Secretary of War by President William McKinley. Root resigned his cabinet position on February 1, 1904 to return to New York and his private law practice. The Roots' summer estate was in Clinton, New York.

Another former politician was Levi Parsons Morton, who had married his second wife, Anna Livingston Reade Street, in 1873. A descendant of George Morton, who landed in Plymouth, Massachusetts on the Ann in 1623, he started his career in the drygoods business. In 1878, he was elected to Congress, was appointed Minister to France in 1881, and in 1889 became Vice President under Benjamin Harrison. He served as Governor of New York from January 1, 1895 through December 31, 1896.

Banker Henry Goldman of Goldman Sachs and his wife, the former Babette Kaufman, had three children. All the residents of 998 Fifth Avenue had impressive art collections, but none, perhaps, surpassed the Goldmans'. Shortly after they moved in, on December 12, 1912, The New York Times reported that Goldman had purchased a "painting of St. Bartholomew by Rembrandt" and said it, "is now adorning the gallery of Mr. Goldman's home." Dr. Wilhelm Bode, the foremost European authority on Rembrandt declared it "to be a splendid specimen of the great artist's work."

Five years later, on January 16, 1917, The New York Times reported that Goldman had added Hans Holbein's Portrait of a Musician to his collection. "The picture cost Mr. Goldman $175,000," said the article.

Three years before that article, the Goldman family's name had appeared in the newspapers for less happy reasons. On May 26, 1914, Robert Goldman, who was 20 years old, "ran away from Williams College, where he was a junior," reported The Evening World, "with Edith Ostend, a chorus girl, and they were secretly married in Jersey City." Goldman's bride was 19 years old. The marriage did not sit well with her new parents-in-law.

Young Goldman was sent to "Ranch L07," a property in Meeker's, Colorado. Calling the ranch "his exile," The Evening World explained, "With an English tutor the boy was sent out there to be a cowboy and to forget his costly experience on Broadway." In the meantime, Henry Goldman had Edith Ostend Goldman trailed.

In court on March 1, 1915, Goldman's private secretary, Chester E. Mann, related that he had headed a raid on the studio of artist Nathan Harris at 66 West 9th Street. He and the investigators climbed down a fire escape and into a window. "Mrs. Goldman was sitting on a couch nude with Harris," he testified. It was the beginning of the end of Robert Goldman's short-lived marriage.

On December 23, 1918, The Evening Post reported, "Mr. and Mrs. Edson Bradley will give a dinner-dance at their apartment at 998 Fifth Avenue on Wednesday evening." At the time, the Bradleys had homes in Tuxedo Park, Newport, Washington D.C. and on Wellesley Island. Born in New Canaan, Connecticut, Bradley was married to the former Julia Wentworth Williams. He succeeded her stepfather, Marshall J. Allen, as president of W. A. Gaines & Co., one of the largest distilleries in the nation. The dinner dance reported on by The Evening Post was just one of the many glittering events that would be held in their apartment.

The New-York Tribune reported on December 21, 1922, for instance, "Mr. and Mrs. Edson Bradley gave a dinner at their home, 988 Fifth Avenue, last night for Bishop and Mrs. William T. Manning. Among the guests were their neighbors, Elihu and Clara Root, along with Lady Maitland, the Chauncey Depews, Mrs. Herbert Shipman, and others.

On June 5, 1924, the New York Evening Post reported that the Bradleys had "closed their home at 998 Fifth avenue and are at the Plaza until they go to Newport for the summer." The couple was in the process of rebuilding their mansion there.

In 1931, the art collection of W. E. Dickerman hung on walls covered in brocaded fabric.

photo by Samuel H. Gottscho, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

Other socially prominent residents were Elliot Fitch Shepard, Jr. and his wife, the former Eleanor Leigh Terradell. Shepard was the son of Elliott Fitch Shepard and Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt, the eldest daughter of William Henry Vanderbilt. On October 20, 1918, The Sun casually mentioned, "Mrs. Elliott F. Shepard, after passing the summer in the Virginia Hot Springs, has returned to 998 Fifth avenue."

Six months after that article, another Vanderbilt moved into 998 Fifth Avenue. On April 5, 1919, the Record & Guide reported that Edith Stuyvesant Dresser Vanderbilt, the widow of George Washington Vanderbilt, had leased "a duplex apartment, especially planned, of 18 rooms and 5 baths."

French paneling and frescoed ceilings made way for modern decor in the Edouard Jonas apartment in 1936. On the walls are Van Gogh's

Portrait of a Peasant; Dancers in the Wings by Degas; and Degas's

Horse with Head Lowered. photo by Samuel H. Gottscho, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

The following year, in July, apartments were leased to Harriet Smith Van Schoonhoven Thorne and Henry Fairfield Osborn. Harriet Thorne's husband, millionaire Jonathan Thorne, had died in January that year.

Henry Fairfield Osborn was born in Fairfield, Connecticut in 1857 to a distinguished family. His father, William Henry Osborn, was a railroad mogul. Henry's wife was the former Lucretia Thatcher Perry. Unlike his industrialist father, Henry pursued an academic career. He was hired in 1891 as a professor of zoology at Columbia University, and subsequently took the position of curator of the Vertebrate Paleontology Department of the American Museum of Natural History.

Another prominent family here by 1926 were the Lewis Latham Clarkes. Born in 1871, Clarke descended from William Ellery, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, on his mother's side; and from Emperor Charlemagne and Henry I of England on his father's. Florence M. Clarke held her own among the socialites in the building in terms of lavish entertaining.

On March 11, 1927, for instance, The New York Times reported that Emilio Axerio, Consul General for Italy had conferred the decoration of Commander of the Order of the Crown of Italy upon Lewis Latham Clarke "at a dinner which Mrs. Clarke gave last night at their home, 998 Fifth Avenue." The article said, "A musical program and supper followed the dinner." Among the 52 dinner guests were elite names like Schermerhorn, Mackay, Baruch, Brokaw, and Harriman.

On April 15, 1912, the year 998 Fifth Avenue was completed, John Jacob Astor IV perished when the RMS Titanic sank. His pregnant wife, Madeleine was rescued and on August 14 their son, John Jacob Astor VI was born. Now, three decades later, he moved into a penthouse here after his wife, Ellen, filed for divorce in Reno in the spring of 1943.

A rumor reached The New York Times that Astor was sharing his apartment with a female named Silvia. As it turned out, however, she was not his latest love interest. On October 29, 1943, the newspaper reported that Astor's butler had taken Silvia to the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital for Animals, noting, "it was known at the hospital as 'the penthouse pig.'" The article described Silvia as, "about nine inches long and about three weeks old."

In the end, an "emphatic" spokesperson for Astor explained that the pig was not a pet, but "one of a litter from Mr. Astor's farm at Basking Ridge, N. J." Because it was undernourished, "Mr. Astor and his chauffeur drove the pig from the farm to the hospital." The animal, "had never been domiciled in a penthouse, never had lived on Fifth Avenue, never had been a pet of Mr. Astor," insisted the statement.

One Sylvia who did live at 998 Fifth Avenue was the fascinating Sylvia Green Wilks. (Her actual name was Harriet Sylvia Ann Howland Robinson Green Wilks, but she was always known as Sylvia.) The daughter of eccentric multimillionaire Hettie Green, she was the widow of Matthew Astor Wilks, the great-grandson of John Jacob Astor I. Sylvia Wilks died in the New York Hospital on February 5, 1951 while living here. She left an estate valued at $94,965,229 (about $1.1 billion in 2024).

In 1953, 998 Fifth Avenue was converted to a cooperative. The storied building continued to be home to some of Manhattan's wealthiest citizens. The 16-room John Jacob Astor VI penthouse was acquired by attorney William Condren, who sold it to Archibald Cox, Jr., son of the Watergate prosecutor, in August 1993 for $5.4 million. It was sold again in 2000. Among the other residents at the time were Morton Hyman, head of Overseas Shipholding Group; private investor Peter Kimmelman; and zoning attorney Samuel Lindenbaum. In September 2017, William P. Lauder, executive chairman of the Estée Lauder Companies, purchased a 14-room apartment on the sixth floor for $23.5 million.

In designating 998 Fifth Avenue an individual landmark in 1974, the Landmarks Preservation Commission called it, "the finest Italian Renaissance style apartment house in New York City."

.jpg)

.png)