The New York Architect, 1907 (copyright expired)

In 1865, less than a decade after the Park Bank was incorporated in 1856, it became the National Park Bank. The following year properties at 214 and 216 Broadway were acquired and esteemed architect Griffith Thomas was hired to design a new headquarters. His striking five-story structure prompted a critic from the Record & Guide to praise, "No building has ever yet been erected in New York which attracted--and justly--more attention and commendation than the Park Bank."

The Griffith Thomas designed building was completed in 1868. photographer unknown, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

At the turn of the century, the National Park Bank had again outgrown its building. In 1901 the trustees purchased adjoining plots to the rear and hired architect Donn Barber to remodel and expand the building. His plans would create a T-shaped structure, with additional facades on Fulton and Ann Streets. On April 1, 1901, demolition of the rear portion of the building began with, according to The New York Times, "the ultimate object, it is understood, of putting up the greatest and finest and highest office building in the City of New York."

The original concept was a 16-story office building that would garner rental income for the bank. But, reported The New York Times in 1904, "mature deliberation resulted in the Directors deciding to have a strictly fire-proof edifice devoted wholly to the business of the bank." The banking functions were moved into the rear portion upon its completion on February 8, 1904, after which remodeling on the Broadway section began. The bank continued business throughout the process with as little upheaval as possible.

The Fulton Street (top) and Ann Street facades. The New York Architect, 1907 (copyright expired)

The New York Times reported on "the wonders and beauties" of the new the rear portion, saying in part:

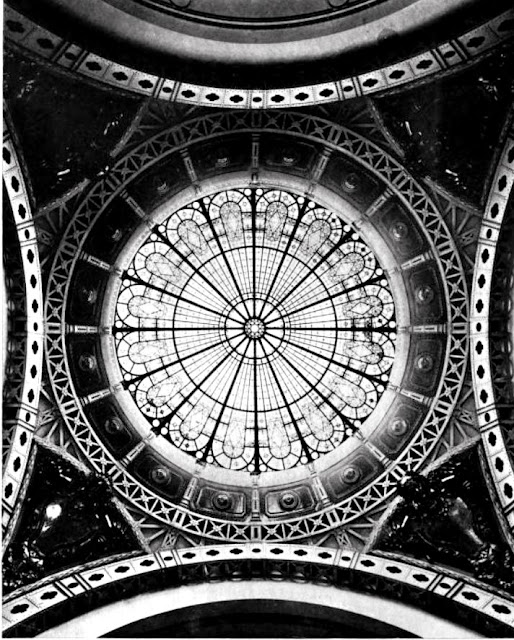

The salient feature of the room is the flood of light that fills its every corner from the windows on Ann and Fulton Streets, and a glazed dome 68 feet above the pink Knoxville marble floor equipped with electric lights on the graduated Dimmer system. North of the dome is an imposing barrel vault 48 feet high, and another and shorter one is south of the dome.

For the first time in the United States, structural beams were exposed in the dome as part of the design. The New York Times said, "the structural iron in it being uncovered and used in the general plan of decoration. The scheme of color takes in buff, sea-green, gold and blue."

Barber used the structural beams as part of the decoration. The New York Architect, 1907 (copyright expired)

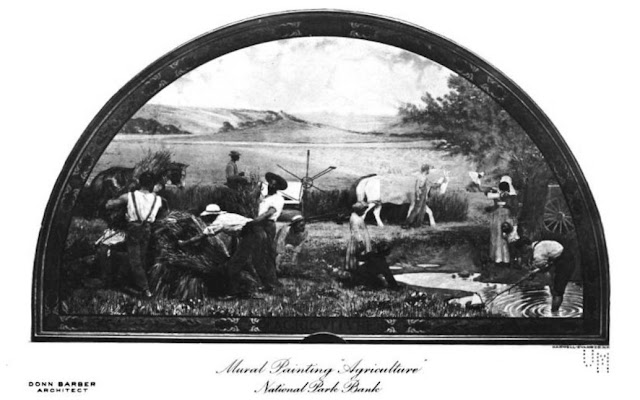

Barber worked with Elmer E. Garnsey on the interior decoration. "Eventually three mural paintings by Albert Herter, now approaching completion in Paris, will complete the artistic features of the building," said the article.

The Broadway section was completed the following year. There was now a second, amber-colored glass dome 70 feet above the floor in the banking room.

American Art in Bronze & Iron noted in April 1910, "Barrel-vaulted rooms intersect these domes, these vaulted rooms being lighted at the ends by huge circular-headed windows, one on Ann street, one on Fulton street, and one on Broadway. The magazine described the floors and walls as being of Tennessee marble and Hauteville marble, respectively. The critic made special note of the tellers' cages.

An especially fine piece of bronze and marble is the counter-screen which separates the banking clerks from the public. The bronze portion rests on a plinth of "Campan Route Melange" marble, the striation of which is of extraordinary beauty, its rich deep tones blending most harmoniously with the patine of the bronze work.

One of the bronze and marble teller cages. American Art in Bronze and Iron, April 1910 (copyright expired)

Albert Herter's three large lunettes, completed in Paris, were shipped and installed in the banking room and entrance hall. They depicted allegories of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce. Donn Barber explained to The New York Times that he did not want to rehash the "the making of money," which had "been symbolized in every conceivable form by almost every great artist since the beginning of banks." Therefore, he instructed Herter instead to depict "the fountainheads" of wealth in America.

A view of the banking room below provides scale to Herter's Agriculture, The New York Architect, 1907 (copyright expired)

On the upper floors were the directors' rooms, meeting rooms, the kitchens and offices. The New York Times reported, "Labor-saving devices abound. They include telephones, pneumatic tubes, electric elevators, and dumb waiters." The article called the building "impregnable," saying, "It could stand a siege." A refrigerating plant supplied "ice water all over the building."

On the evening of July 20, 1906, bank clerk Edward Frost was arrested on Lexington Avenue. The New-York Tribune said that the bank's cashier, Maurice Ewer, had accused him of theft. When visited at his house, Ewer had little to say. "Frost stole $150, just as the warrant states. That is all I have to say."

Ewer was most likely being taciturn to buffer the bank from bad press. In fact, after Frost was sentenced to Sing-Sing prison in August, The New York Times reported, "The offense to which he pleaded guilty was that of stealing $150, though the amount of his peculations is said to be between $5,000 and $12,000." That amount would translate to more than $400,000 on the higher end in 2023.

Looking from the banking floor toward Broadway, the entrance is seen under the marble stairs leading to the slightly elevated "Officers' Quarters." The New York Architect, 1907 (copyright expired)

The view from the Officers' Quarters above the staircase looking back to the banking floor. The New York Architect, 1907 (copyright expired)

Among the clients of the National Park Bank was the eccentric millionaire Hetty Green. She ran her personal life as strictly as her business life, as evidenced on February 19, 1909 when she used the bank vaults to interview her daughter's suitor. The Evening World began an article saying, "Matthew Astor Wilks faced the crisis of his life to-day. Mr. Wilks met Mrs. Hetty Green by appointment at 2 o'clock this afternoon, and for half an hour was put through a severe course of sprouts on banking, real estate and coupon cutting."

Before the meeting, Green explained to the The Evening World reporter, "Mr. Wilks, what I have seen of him, is all right. I have heard him talk, but I have heard other beaux of Sylvia talk...Mr. Wilks comes of fine stock. His mother was a Langdon. But I want to know him better." Happily for Wilks, he passed inspection. He and Sylvia Ann Howland Green were married on February 23.

Working as a clerk in 1920 was 18-year-old Rinaldo Sidoli, who, according to the New York Herald, daydreamed "of the day when, as his mother was always telling him, he should be a great violin virtuoso." That year, a Liberty Bond worth $1,000 went missing. Then, on January 13, 1921, another $14,000 worth of the bonds disappeared. On January 31, Sidoli resigned. The New York Herald commented on June 21, "in the minds of some of the bank officials finally came the suspicion that there was more than a coincidence in the clerk's resignation." Later that spring, private detectives were put on his trail.

They soon reported that Sidoli was studying violin with "one of the best known teachers in the country, and that under his arm he usually carried a mighty expensive violin." The detectives made inquiries, and were told that the instruments were worth over $2,700. The 20-year-old "would be virtuoso," as described by the New York Herald, booked Aeolian Hall for April 4. He intended his concert that night to be his introduction to the music critics. Instead of a basking in his grand debut, however, Sidoli stepped into a trap.

At 8:15 Sidoli walked onto stage. The New York Herald recounted, "Seated in the auditorium he could see just four persons, all men. One was a detective, another was an assistant to Mr. Main [Sidoli's former supervisor in the National Park Bank]. The others were critics." Sidoli was arrested the following day. "He had spent the $14,000, all but ten cents," reported the New York Herald.

Along with their prisoner, officers brought the two violins to the station house. The New York Herald reported on June 22, "One of them, for which Sidoli says he gave $1,800, bore the inscription 'Laurentius Storioni Cremo, 1604"; the other, said to be worth $900, was marked 'Carlo Bergonzi, 1750.' Several musically inclined detectives drew bow across the strings, at which Sidoli was observed to shudder."

A disturbing incident occurred on an upper floor the following year. On December 29, 1922, the bank president Richard Delafield, met with two of his vice-presidents. One of them was William O. Jones who had been with the bank for 23 years. The New York Times reported, "He was seated near the desk of the President and was about to speak to another Vice President of the bank when he suddenly threw his head back and raised his hands, then lurched forward on his arms." Jones had suffered a fatal heart attack.

Jones's wife was, according to bank officials, seriously ill. The Evening World reported, "the hope was that the information of his death might be withheld from her until she could be prepared for the shock, the effect of which it was feared, might result in her death."

On May 24, 1929, just months before the Stock Market collapse, the stockholders approved the organization of an affiliated securities company, the Parkbank Corporation. That same year the organization merged with Chase National Bank.

The bank continued to operate from Donn Barber's magnificent structure until its demolition in 1961. It was replaced by the 27-story tower designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon Associates.

many thanks to reader Doug Wheeler for suggesting this post

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

Wow. Extraordinary Building. I shouldn't, but I find myself feeling sorry for for the violinist who stole for his art

ReplyDelete