image vi cityrealty.com

In 1896 the Board of Estimate and Apportionment approved $30,000 "for a site at Nos. 164 and 166 West Seventy-fourth street...intended for the quarters of a new hook and ladder company." But before the project went forward, a substitute site was selected on West 77th Street. The change in plans created a prodigious opportunity for real estate developer Louis P. Sefton.

He purchased the two three-story buildings on the lots in 1901 and hired the architectural firm of Buchman & Fox to design an upscale residential hotel. Completed the following year at a cost of $150,000 (nearly $5 million today), the seven-story Marbury Hall was a restrained example of the Beaux Arts style. An impressive portico, upheld by polished stone columns, sheltered the entrance. It was crowned by a stately broken pediment. The openings of the lower five stories were treated differently floor-by-floor, while those of the sixth floor were flanked by the massive full-height brackets that upheld the stone balcony of the seventh.

photo by Wurts Bros., from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

The suites in Marbury Hall ranged from one to three bedrooms. An advertisement in the New-York Tribune on September 21, 1902 called it "an exclusive residence hotel for small families and bachelors." The ad touted uniformed Japanese attendants, valet service, and "domestic cuisine, with superior service." Rents ranged from $540 to $1,700, or about $4,650 per month for the most expensive.

The New York Herald called it "A house with the atmosphere of a rich man's country house," adding, "Marbury Hall is the most sumptuously appointed establishment in this city. The decorative effects and furnishings are in exquisite taste. Its many distinguishing features have attracted unusual attention."

On October 10, 1902, the New-York Tribune wrote:

This house has attracted unusual attention on account of its many distinguishing features as a place of permanent residence for an exclusive class of people...Its particular attraction seems to be its homelike atmosphere. The furnishings are of a sumptuous character, but withal in good taste. The house is managed by a young woman, and it is due to her artistic taste and womanly instincts that Marbury Hall is already an established success.

That manager was Catherine E. Sefton. Louis P. Sefton and his wife were among the initial residents of his building. Their tenants, expectedly, were professionals. Among them was educator John Green Wight, a Civil War veteran and president of the Schoolmasters' Association of New York.

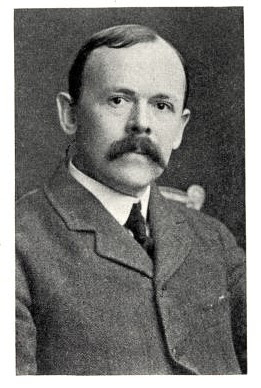

Other initial residents were Dr. Carleton Lewis Brownson and his wife, the former Caroline Louise Barstow. The Yale-educated Brownson was Dean of Faculty at the College of the City of New York. Like Wight, he had served in the Civil War.

Carleton Lewis Brownson, Quarter-Century Record of the Class of Eighteen-Eighty-Seven, Yale College, 1915.

In 1909 Catherine Sefton hired Louise B. Decker as the bookkeeper. Her salary was $35 a month plus board. Six years later, in the spring of 1915, Louise's pay was raised to $60 a month.

Early that year Catherine Sefton became ill and went away "for a rest," in her words. She later said, "When I returned, Mrs. Decker gave me a statement of the hotel's finances, and I saw from it that business seemed to have gone all to smash. When I asked Mrs. Decker about it she replied that business had been bad everywhere." Suspicious, Catherine told Louise Decker to take a two months' vacation. She arranged a trip to Block Island, Narragansett Pier and Newport. Catherine told a reporter from The Evening World, "No sooner had she gone than I called in a public accountant and placed the books in his hands. In less than ten minutes he told me that I had been robbed."

On October 30, 1915, The New York Press headlined an article, "Tango Crazed Woman Seized As A Thief," and reported, "Accused of stealing to satisfy her longing for the tango parlors of Broadway, Mrs. Louise B. Decker, head bookkeeper of Marbury Hall...was arrested late yesterday afternoon by Detective Boyle." The arrest did not go as expected. "As the detective told her she was under arrest, Mrs. Decker raised her hand to her mouth and swallowed a quantity of nitrate of silver." She was taken to the Polyclinic Hospital where the poisoning was caught in time.

Over a period of years Louise Decker had absconded with $10,000 of the hotel's money--more than a quarter of a million in today's dollars. How she supported her lifestyle suddenly became clear to Catherine Sefton. She told the New York Press,

Mrs. Decker has given dinner parties in Broadway's most expensive tango places. She gave box parties at all the theatres. She was well known at all the dance places, and I have heard that she has paid a professional dancer $10 to take her around to the tango parlors, and she paid the expenses of the evening. She was always the best dressed woman about the hotel, and when I asked her about it, she said she had wealthy relatives who gave her a generous allowance.

From her hospital bed, Louise Decker did not seem especially repenting. The New York Times wrote, "'I want to die, I want to die,' she murmured to Detective Boyle. 'I've been good to a lot of people. Now they have gone back on me. They are a lot of pikers, that's what they are.'"

Catherine E. Sefton sold Marbury Hall to Edward Arlington in January 1921. The Brownsons were still living here at the time. That year Carleton Brownson philosophized on the state of democracy in the Thirty-Fifth Year Record, Class of 1887, Yale College, saying in part:

We have found out that after all there is no magic in democracy unless the raw material of your democracy is exceedingly good. And there is no short-and-easy method of making it so. Consequently there is danger that the thing won't be done...All the same, I rather think that in the long run the world is still going to be ruled by the intelligent, however much they may be outnumbered.

Also living here at the time was the famous Rev. Dr. Charles Henry Parkhurst and his wife, Ellen Bodman. The former rector of the Madison Square Presbyterian Church, he had been president of the New York Society for the Prevention of Crime. He was noted for going into the streets at night in disguise and frequenting barrooms, gambling houses and brothels, presumably to collect evidence. He had famously waged war against Tammany Hall from the pulpit, and denounced women's suffrage as "self exploitation indulged in by short-haired women and encouraged by long-haired men."

Ellen Bodman Parkhurst died on May 26, 1921. Four years later Rev. Parkhurst retired to Lake Placid. He explained to a reporter from his apartment on April 22, 1925, "New York isn't what is used to be. Not that the people aren't just as good. It's the noise, dirt, automobile smoke and crowds." Nevertheless, Parkhurst retained his Marbury Hall apartment. The Sun noted, "He has not given up his legal residence in New York, however, and will return to the city from time to time."

The crime-0bssessed Parkhurst would have been outraged over two new residents in 1929. Real estate operator Alfred Cohen and his wife Gladys were married in June and moved into Marbury Hall. One month later, on July 25, detectives who were acting on a tip, searched their apartment. The New York Times reported, "An opium smoking layout and a half pound of alleged opium were found in their apartment."

Cohen had been arrested on a charge of possession of narcotics on February 25, 1928. Now he and Gladys "disclaimed all knowledge of the layout and alleged opium," said The New York Times. The article added, "Mrs. Cohen wept continually." Both were arrested and charged with possession of narcotics.

Once touted as "the most sumptuously appointed establishment in this city," in 1945 Marbury Hall was converted to house "residents for missionaries of a religious organization," as documented by the Department of Buildings. The ground floor now held the lounge, reception room, library and dining room; and upstairs were 18 "study and bedrooms" per floor.

In 1972 the building became home to the Phoenix House Foundation. The non-profit is today among the country's preeminent substance abuse prevention and treatment service organizations. It operated from the building for nearly 45 years, selling it for $26.8 million in February 2016 to Greystone Development and Prime Rok Real Estate.

A gut renovation by Barry Rice Architects completed in 2020 resulted in two apartments per floor. Because the building, now known as The Marbury, sits within a historic district, the exterior retains its 1902 appearance.

many thanks to reader Matthew Hall for prompting this post

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

As usual, your meticulous research has turned up quite a cast of characters. Love the long-haired men and short-haired women line! Louis P. Sefton transitioned to Louise P. Sefton in paragraph 7. Probably a typo but, maybe not!

ReplyDeletePhyllis! I was wondering about you lately. Thanks for catching the typo. All fixed! Hope you're well.

DeleteIn 1927-28, according to the "Who's Who of Hotel Men", S. Gregory Taylor was the "part owner and manager" of Marbury Hall. He later went on to own and manage the Montclair, Dixie, and most famously, the St. Moritz.

ReplyDelete