The eight, five-story brick houses at the northwest corner of Central Park West and 93rd Street were demolished in 1909 to make way for a modern apartment building. The Sturtevant Realty Co. had hired architect Albert Joseph Bodker to design the 12-story structure. His plans projected the construction cost at $750,000--or a staggering $22 million today.

The Turin was completed in 1910. Bodker had made ventilation and natural light a priority. Architects' and Builders' Magazine noted, "The 'Turin'...is a very large apartment house in the design of which much space has been allowed for the street-opening courts to light the inner rooms." An advertisement boasted, "all outside rooms," meaning that each room had a window. To achieve that, the building's footprint navigated four light courts which reduced the possible number of apartments but increased their livability.

The unusual shape of the structure is evident in the floorplan. Central Park West is to the right. Architecture, April 15, 1911 (copyright expired)

The apartments ranged from five to nine rooms. Residents would enjoy the latest amenities. The Real Estate Record & Guide noted it contained, "two electric passenger elevators, four electric service elevators, one electric freight elevator and one sidewalk elevator."

The tenants were professionals, like Ralph M. Stauffen, who was assistant treasurer and a director of the Lord & Taylor drygoods store, and president of the Newark-based Hahne & Company. Another early resident was Caroline Adler, the widow of dry goods merchant Samuel Adler. Caroline was known fondly as the "grandmother of the Jewish orphans." The sister of Abraham Abraham, one of the founders of Abraham & Straus department store, she devoted her life to Jewish charities, most notably the Hebrew Orphan Asylum. She was appointed vice president of the institution in 1893, and still held the position when she died in her apartment here on December 5, 1918.

Relations within the family of George M. Ehrgott were stressed in 1919. The stock broker's wife had begun a suit for separation, and his young son, George, Jr. was rebelling (possibility because of his parent's strained relations). Police were no doubt surprised when the boy walked into the police station on August 1.

The Sun reported, "George M. Ehrgott, Jr., 11, preferred charges against his father in West Side court yesterday for horsewhipping him. The boy showed Magistrate Tobias a number of welts across his back and around his legs." He said that his father had telephoned him, told him to come to his aunt's house on West 96th Street, and then beat him. The newspaper noted, "Mr. Ehrgott admitted the whipping in court, but said his son fully deserved it."

"'I love my son,' he said, 'but he is too much for me. When I called him up and asked him to meet me he refused at first, saying I was a 'bad papa.'"

Ehrgott was held on $500 bail for trail.

Resident George Greenway Smith met a bizarre death in 1920. The 45-year-old and three friends took an automobile to Asbury Park, New Jersey for an outing on Saturday, October 9. That night before returning home, they stopped in a Main Street restaurant for "a pancake feast," as worded by the New-York Tribune. Three of the party grew seriously ill, and Smith died from what the article called "poison pancakes." It explained, "The death certificate issued for Smith gave arsenic poisoning as the 'probably cause of death.'" The night manager who made the pancakes and the waiter who served them were arrested.

Typical of the Turin residents were importer Edward Kalisher, his wife Theresa, and their daughter Eleanor Betty. Kalisher was a partner in the importing firm of Kalisher & Steinberger. He died in February 1921, and his funeral was held in the apartment.

The following year, when their mourning period had passed, Theresa and Betty summered in Lake Placid, New York.

On September 10, 1922 The New York Herald reported on Eleanor's 18th birthday celebration at the Grand View Hotel. "The guests came in costume, and for the occasion the hotel cafe was decorated in old time manner, with log fire at one end." Later, at midnight, the 70 guests enjoyed a "camp supper" cooked in the open by an Adirondack guide.

Living in an eight-room apartment in the Turin at the time was John H. Sutphen, described by The Daily Argus as a "member of a prominent south New Jersey family." He was estranged from his wife and five-year-old son, who lived in New Jersey, and, rather shockingly, shared his apartment with Katherine Deneston.

Sutphen's mother died in August 1923. Her estate was divided among Sutphen and his two sisters, his portion "said to be more than $100,000." (The windfall would equal about $1.5 million today.) One week later, on Saturday night, August 25, Sutphen and Katherine went out with Katherine's sister and brother-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. Robert C. Spohn. According to Spohn, they started out at the Moulin Rouge on Broadway and 50th Street and ended up at a night club at 110 East 59th Street, leaving at 4:00. They returned to the Turin apartment around 4:30 in the morning.

Spohn told investigators they sat up until around 6:30, then everyone other than Sutphen went to bed. Katherine said he "kissed her good night and said that he would sit up a while." Half an hour later, Sutphen telephoned a business associate, Ernest A. Dunlea saying he was "very ill" and asked him to hurry to his apartment. Dunlea and another business associate, Julius Beekman, rushed to the Turin. When no one answered the telephone, the desk clerk took them up and used a passkey to enter. Sutphen was found dead on the sofa in the drawing room, a victim of cyanide poisoning.

Police now had a mystery on their hands. Had the millionaire killed himself or was he murdered? Why would he call a friend to help him when he could have wakened any one of three people in the apartment? According to Dunlea and Beekman, Stuphen "had placed money in a business that would have netted him a big sum this week." And investigators were informed that there were parties who could benefit from his death.

Three days later, Assistant District Attorney James J. Wilson ruled his death self-inflicted, adding that Sutphen lived "at the rate of $75,000 a year," and "played Broadway nightly, spending $500 a week to tip waiters." The implication was that his "fast living" had driven him to self destruction.

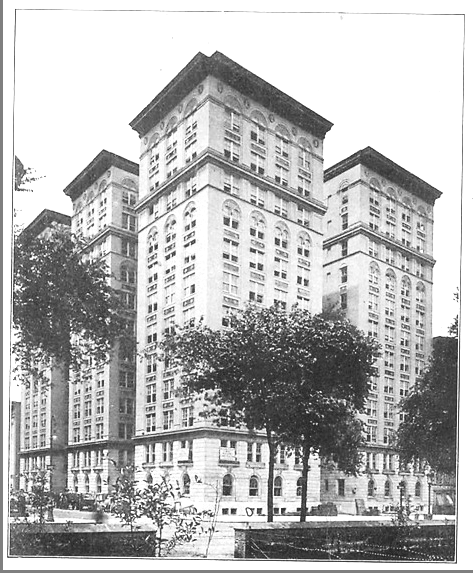

In 1912 the Turin was the tallest building along Central Park West. A canvas marquee stretched from the entrance to the curb. The Edison Monthly, June 1912 (copyright expired)

The Turin continued to house well-heeled residents, like Edward Angly and his wife, the former Elizabeth Mary Wadsworth, here at mid-century. Angly was a well-traveled war correspondent and author. From 1922 to 1930 he worked in London, Paris, Berlin and Moscow for The Associated Press. In 1936 he joined The Herald Tribune, becoming the head of it's London bureau in 1939. During World War II he covered the front lines in Flanders and Bordeaux, and was present at the Battle of Britain. Angly was among the first American correspondents to reach Pearl Harbor following the attack of December 7, 1941.

In the summer of 1968 film critic Pauline Kael and her daughter, Gina, moved into a 12th-floor apartment. Her biographer, Brian Kellow commented in his 2011 book Pauline Kael, A Life in the Dark, "It was a famous building on the West Side because of the intensity of its social life, and many leftist writers and academic types lived there."

Not so left-leaning was Rene d'Harnoncourt, the director of the Museum of Modern Art, and his wife, the former Sarah Carr. He joined the museum in 1944. When Nelson Rockefeller established the Museum of Primitive Art in 1957, the Austrian-born d'Harnoncourt became its vice president. He retired from the Museum of Modern Art in July 1968. A month later he and Sara were at their summer home in New Suffolk, New York where he was struck by a car and killed.

Another resident affiliated with the Museum of Modern Art was Peter Selz, who became its curator of painting and sculpture exhibitions in 1958. Paul J. and Ann Heath Karlstrom, in their 2012 biography Peter Selz: Sketches of a Life in Art, noted that he and his wife, Thalia, "lived well, in a large apartment at 333 Central Park West...Peter and Thalia socialized with couples well known in art and literary circles, among them Lionel and Diana Trilling."

In the winter of 1980, journalist and editor Andrew Cockburn, his wife, investigative journalist and filmmaker Leslie Cockburn, and their daughter Chloe, moved into the Turin. In her 1998 book Looking for Trouble, Leslie writes, "the landlord screened tenants for creativity. Mr. Sheldon chose writers, composers, filmmakers, actors. 'Over the Rainbow,' originally 'Somewhere on the Other Side of the Rainbow,' was composed at 333."

Essentially unchanged today, the Turin was a pioneer in the transformation of Central Park West from rowhouses and resident hotels to the majestic apartment buildings for which it is known today.

photographs by the author

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

"His mind wandered away to the question of what May's drawing–room would look like. He knew that Mr. Welland, who was behaving "very handsomely," already had his eye on a newly built house in East Thirty–ninth Street. The neighbourhood was thought remote, and the house was built in a ghastly greenish–yellow stone that the younger architects were beginning to employ as a protest against the brownstone of which the uniform hue coated New York like a cold chocolate sauce; but the plumbing was perfect."

ReplyDeleteWhere do you suppose Wharton was thinking of when she wrote this? 99 Park Avenue (where Andrew Haswell Green lived? She apparently rented nearby)? 114 East 39th? Although, if I'm not mistaken, based on what I've read of your other East 39th posts, the 5th Avenue bits during the Gilded Age were mostly stables? So perhaps it was further down?

It would be better if questions not related to the post were sent directly to my email address above. Wharton did not have to have a specific, existing structure in mind. This was fiction, so she had broad creative license.

DeleteUnderstood Tom, thank you. The Turin is a fascinating building!

DeleteThe loss of the large cornice gives off the appearance as if the roof has been ripped off and the building cut down in size, very regrettable. NYarch

ReplyDeleteFloor plan has the layout look and light courts of the massive Ansonia Hotal.

ReplyDeleteYou cannot UNSEE that missing cornice now. Had it remained, the Turin would overshadow every limestone Italianate building on Fifth Ave!

ReplyDelete