In 1948, real estate developer Joseph Perlbinder demolished a row of mansions at 28 through 36 East 36th Street as the site of a modern apartment building. Completed in 1949, architect Hyman Isaac Feldman (who went professionally by his first initials) designed the 11-floor-and-penthouse structure in the late Art Moderne style. Its entrance, capped with a wavecrest entablature, sat within the limestone base that stair-stepped from one to two floors, then to four at the center. At the topmost floors, setbacks allowed for railed terraces.

Corner-wrapping casement windows had been in vogue for a generation; but at 36 East 36th Street, Feldman's were different. He rounded the corners of the recessed sections, then used long, thin panes that allowed the windows to follow to gentle shape.

The cover of the 1949 real estate brochure pictured the building. from the collection of the Avery Library of Columbia University.

Despite the relatively small size of the apartments (most had just one bedroom), the residents were well-heeled. Among the first were Julia Green Sturges and her daughter Cary. Julia, who was the daughter of Thomas Dunbar Green, president of the American Hotel Association, was divorced from Perry MacKay Sturges, who lived in Princeton, New Jersey. Cary's marriage to Alan Lincoln Burns, Jr. in St. James Protestant Episcopal Church on June 17, 1950, was highly covered in the society pages.

Two months later, The East Hampton Star reported on the "very interesting house" designed by A. M. Shoemaker that residents William C. Eberle and his wife Cora were constructing in East Hampton. Saying "Mr. and Mrs. Eberle will use the house as a summer home," the article mentioned, "Mr. Eberle is a prominent engineer who has been sent by President Truman as an adviser to various parts of the United States and South America." Eberle was a partner in the fuel consulting firm Eberle & Leyford, Inc.

In 1949, Meyer Lansky and his second wife, Thelma Schwartz, moved in. Perhaps because of his shady occupation (he was known as the "Mob's Accountant"), Lansky did not stay long at one address. Since signing a lease at 411 West End Avenue in 1941, he had lived at 211 Central Park West and 40 Central Park South. The Government, however, managed to keep up with his movements. A year after moving in, he was subpoenaed to testify before Congress's Hearings to Investigate Organized Crime.

The committee was not successful in obtaining much information from Lansky. He was asked, for instance, by Senator Estes Kefauver, "May I ask you, did you bring all these books and records we asked for?"

Lansky answered, "No."

When asked why he had not complied, Lansky replied, "I decline [to answer], on the ground that it may tend to incriminate me."

Asked, "What is your business," he answered, "I declined to answer on the ground that it may tend to incriminate me."

And so it went.

Lansky would eventually die of lung cancer in Miami Beach in January 1983.

In 1951, Russian-born author Ayn Rand and her husband, actor and painter Charles "Frank" O'Connor, moved in. The couple had met on the set of the 1927 silent film The King Of Kings and were married in 1929.

They had been living on a ranch in California. In her Ayn Rand and the World She Made, Anne C. Heller writes, "On October 24, they took occupancy of apartment 5-A. Their furniture had preceded them by a day, but the apartment was small, and much had been left behind." Heller describes it as:

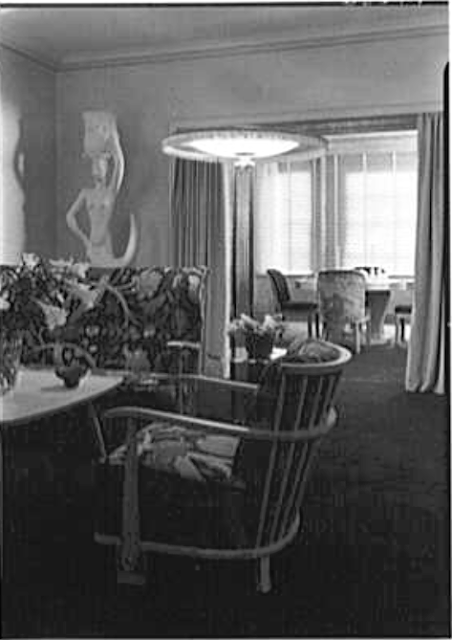

...not only relatively small but also plain. First-time visitors, expecting Roarkian grandeur along the lines of the Neutra house, were surprised by its modesty. An entrance foyer doubled as the dining room, with a black-lacquered table, designed by O'Connor, pushed against a mirrored wall. Formal dinners were eaten there; otherwise, the table served as a work surface for a series of manuscript typists. A small kitchen opened off the foyer. The living room was small, with windows on the far wall, and was decorated by Frank with mid-century modern chairs and a black tweed sofa, glass-topped tables, and green-blue pillows and knickknacks strewn around. There was one bedroom and a tiny study facing an air shaft, from whose single window she could see the Empire State Building, if she leaned out and peered west.

Writer and editor Evan Welling Thomas 2d and his wife Anne lived here at the time. Born in 1920, Thomas was the son of former Presidential candidate Norman Thomas. Evan's war memoir, Ambulance in Africa was published in 1945, the same year he joined Harper & Brothers as an editor.

In his book, Controversy and Other Essays in Journalism 1950-1975, author William Manchester talks of meeting with Thomas here while writing his 1967 Death of a President--the book about the five day period before and after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Manchester said, "it was then that I began to understand the depth of his feeling on this issue."

Among the other notable books Thomas would edit were Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis by Robert F. Kennedy, and Eleanor and Franklin by Joseph P. Lash.

Charles Kurzon lived here by the early 1960s. He was president of Charles Kurzon, Inc., which dealt in architectural and finishing hardware. Kurzon hardware was used in important Manhattan structures like the Time & Life Building, the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and the New York Coliseum.

An interesting figure residing here at the time was Nathaline Frackman. A 1925 graduate of Columbia University, The New York Times said she "devoted her career to arranging social and business parties." Using the pseudonym Nata Lee, she wrote The Complete Book of Entertaining, Nata Lee's Guide for Every Hostess. She died in her apartment at the age of 74 on January 27, 1977.

Other than replacement windows, H. I. Feldman's late Art Moderne design, which borders on mid-Century Modern, is little changed.

many thanks to reader Lowell Cochrane for suggesting this post

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)