The gracious Brevoort mansion was the first stately home built on Fifth Avenue. When Henry C. deRham (whose family had purchased it from the Brevoorts in 1850) sold the house to George F. Baker in 1921, the neighborhood had changed from one of fine private residences to one of apartment buildings. The Bakers resold the historic mansion in 1925 to the New York Fifth Avenue Hotel Corp., which announced plans to demolish it. Not everyone was pleased with this sign of progress. On April 8, 1925, The Outlook lamented, "But the old Brevoort mansion is to be destroyed, to make way for another apartment-house and the modernization of that section of the avenue will be practically complete—and wholly depressing to those who love some flavor of the past.”

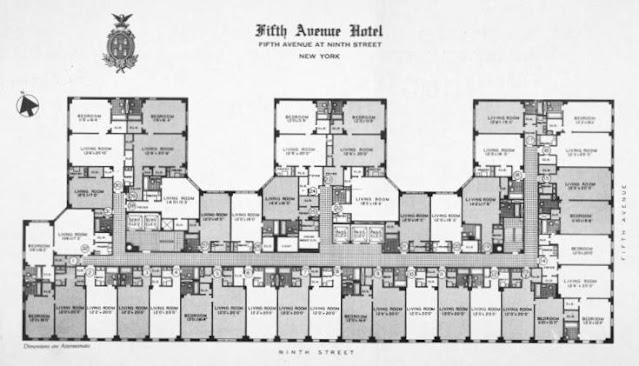

The developer hired architect Emery Roth to design a 15-story building on the site. Residential hotels had been popular for decades. Like apartment buildings, they offered long-term leases. But like hotels, they provided maid service and there were no kitchens in the suites. Residents took their meals either in the in-house dining room or off site. The Fifth Avenue Hotel would be slightly different from what New Yorkers were accustomed to. While most residential hotels offered sprawling suites, those in The Fifth Avenue Hotel ranged from just one to three rooms.

The one-room apartments (what today we would call studios) were designed much like rooms in transient hotels. from the collection of Columbia University Libraries

Above a two-story stone base, Roth clad the building in variegated beige brick. Below an impressive glass-and-metal marquee, a bronze doorway was recessed within an ornately decorated arched entrance. The upper floors were embellished with romantic, Spanish Renaissance details like faux balconies, and two-story arcades with turned terra cotta columns.

The managers highlighted the convenience of city living in marketing the apartments. An advertisement on June 26, 1926 said in part, "Don't grin and bear it, caught in the daily subway mob. Live at the new Fifth Avenue (apartment) Hotel, and smile at traffic jams as reported in the papers. Travel against the crowds." It went on to describe:

1, 2 and 3 rooms with serving pantry and automatic refrigeration. Furnished or unfurnished. Maid service included in lease. Owner-managed restaurant. Time saving convenience of Washington Square.

The Fifth Avenue Hotel opened on August 1, 1926. Despite their small accommodations, the residents were professional and often well-known. In addition to the in-house restaurant, female residents enjoyed the convenience of a hair salon in the building.

Life within The Fifth Avenue Hotel continued with little variation until the death of owner Ely Rabin on August 7, 1964. A decade later, residents would begin noticing changes.

Before then, however, residents included Lorna Dietz, the former music editor of the American Book Company. A graduate of the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music in Milwaukee, she received further degrees from the Milwaukee-Downer College, the University of Wisconsin, and Simmons College in Boston. She joined the American Book Company in 1926, the year The Fifth Avenue Hotel opened, and retired in 1963.

Two other residents at the time were Jacob H. Cohen and Thomas C. Meeks. A widow, Cohen was born in Odessa, Russia and came to the United States in 1900. He was the president of the Forest Box and Lumber Company. By the time he died in his apartment here on July 6, 1964, he had given "many thousands of dollars to Jewish religious, charitable, health and other organizations," according to The New York Times. The Jacob H. Cohen Clinic for emotionally disturbed children, opened in 1960, was named for him.

Thomas C. Meeks was also widowed. His wife, Charlotte, had died in 1960. He was assistant vice president of the Hanover Bank at the time of his retirement in 1955, although he remained on the advisory board of the Manufacturers Hanover Trust Company. From 1939 to 1942 he was president of the National Democratic Club.

A most colorful resident was David Dubinsky, living here with his wife, the former Emma Goldberg, as early as 1966. Born in what is today Belarus in 1892, he became involved in the labor movement early on. During the Russian Revolution of 1905, he joined a bakers' union. By the age of 15, he was the leader of the local labor union. It did not end well. He was sentenced to hard labor in Siberia the following year. Somehow, the teen managed to escape on the way there, and made his way to New York City in 1911 at the age of 19.

By the time the Dubinskys moved into The Fifth Avenue Hotel, he was a nationally-known labor leader. As head of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, he had met numerous Presidents, was influential in the forming of the CIO, and was a founder of the American Labor Party and the Liberal Party of New York. He retired from the ILGWU at the age of 74 on March 17, 1966, while living here.

Despite his age, every Sunday Dubinsky took a two-hour bicycle trip to Central Park in good weather. He grumbled to a New York Times reporter in 1972, that his candy-colored, luminescent purple bicycle was "the fifth bike I've had since my first one in 1937. They stole four on me." He encountered another type of crime that year.

On the morning of February 20, 1972, Emma Dubinsky was ill, and David (whose 80th birthday was the next day) noticed there was no breakfast milk. He headed in the snow to a store at University Place and 10th Street. He had not gotten far before he was mugged. He told a reporter, "...about 50 feet from Fifth Avenue, a guy gives me a push into the entryway. It's three steps down and naturally I'm falling some and he jumps on me."

The mugger grabbed Dubinsky's checkbook, tossed it aside, then pulled his wallet containing $90 from a different pocket and fled. Dubinsky recounted, "'Catch a thief!' I'm screaming, and a man and a woman on the corner are standing like dummies--they don't move. People are afraid, you know." He reflected, "Not even in the old days did such a thing happen to me." (Dubinsky continued to the store and bought his wife's milk on credit.)

At the time of the incident, Captain Mario Taddei and his wife Maria lived here. Born in Italy, Taddei came to America in 1936. The president of two shipping companies, he and Maria maintained a home in Genoa-Nervi, Italy.

Another resident was Philip T. Hartung, the film critic for Commonweal magazine. He had also consulted for the United States Catholic Conference's division of films and broadcasting since 1958, and was a committee member on exceptional photoplays of the National Board of Review. From 1942 to 1945 he worked in the film library of the Museum of Modern Art.

The Fifth Avenue Hotel Restaurant, which had been open to the public for some years, was replaced by Feathers in 1972. On August 25, 1972, The New York Times critic Raymond A. Sokolov commented, "This plush new Greenwich Village cafe restaurant in the Fifth Avenue Hotel looks and feels very Upper East Side."

Author and journalist Ben Lucien Burman and his artist and illustrator wife Alice Caddy Burman were residents at the time. Using her maiden name professionally, Alice Caddy illustrated a series of popular books by her husband. The New York Times said of her,

She traveled in the Arctic and the Sahara, the jungles in Africa, Borneo and New Guinea to do her art work. She lived at times among former headhunters and cannibals. She also helped her husband, a war correspondent for The Reader's Digest and the Newspaper Enterprise Association, on his assignments in the Middle East during World War II.

Alice Caddy also illustrated Ben Burman's Catfish Bend series, traveling on Mississippi River boats to glean ideas. On August 4, 1977, The New York Times noted that the Catfish Bend books were being made into a feature film by Walt Disney Productions, and "Ed Padula is scheduled to make [them] into a Broadway musical."

Emma Goldberg Dubinsky died at the age of 80 in their apartment on December 25, 1974. Her husband would survive her by eight years, dying on September 17, 1982.

A celebrated couple lived here at the time of Emma Dubinsky's death--23-year-old soul-rock singer Stevie Wonder and his wife, Yolanda. Expecting their first child that year, they began looking for a more permanent home. They found it in January 1975, a "Civil War-period brownstone home near Stuyvesant Square," reported The New York Times on January 31, 1975.

According to The Villager, later, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix had also briefly stayed here. And the staid residents of The Fifth Avenue Hotel would see another rock presence a few months later. On May 2, The New York Times reported "The [Rolling] Stones one-song concert yesterday was staged for their press conference at the Fifth Avenue Hotel. The whole operation--which was broadcast on some rock ratio stations--lasted only 10 minutes."

That year, ownership of The Fifth Avenue Hotel was taken over by Daniel and Nathan Brodsky and other investors. Residents began seeing changes. The maid and linen services, for instance, originally included in the rent, were now optional "for roughly the same cost the hotel pays for them," according to Brodsky.

In January 1978, Feathers, which The New York Times had deemed "plush," was ruffling feathers among the residents. The Villager reported "the restaurant and catering establishment on the ground floor of the residential high rise that used to be the Fifth Avenue Hotel," was being called "on the carpet in the wake of a raucous disco party, December 30." It was not an isolated incident. One resident said that tenants on the second and third floor would leave for the weekend in anticipation of the loud disco parties.

David Brodsky pushed back, saying "no tenants have been told that 24 Fifth Avenue was an apartment building," and that "about 50 tenants in the 430-unit building now use the [linen and maid] services. A compromise of sorts was reached when new restrictions were put in place on August 15, 1983 that limited "the amount by which hotel operators may increase the rent for long-term tenants in rent-stabilized hotel rooms," said The New York Times.

The restaurant space saw a succession of eateries over the next decades. In 1988 Mosaico opened, followed by 24 Fifth Avenue in 1991. That was replaced by the Rose Cafe in 1995, which stepped aside for the Washington Park in 2001. The Lotus of Siam was replaced by Claudette in 2014.

Through it all, Emery Roth's hand painted 1926 Spanish Renaissance lobby was never updated. It was recently carefully restored by Evergreene Architectural Arts, bringing the brilliant colors and gilding back to life.

photographs by the author

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.jpg)

.png)

You can also buy these apartments. The building is on a land lease.

ReplyDeleteThanks for a great story in history. By the way, I enjoyed listening to you on the Gilded Gentleman podcast discussing Bertha Palmer.

ReplyDelete