In July 1871, when Albert Levi broke ground for a four-story brick store at 56 West 14th Street, just east of Sixth Avenue, the district had transformed from high-class private homes to boarding houses and stores. On Sixth Avenue, steps away from Levi's site, Rowland Hussey Macy had operated his fancy goods store since 1858. Macy had started out with a small shop, living above it with his family. Starting in 1863 he expanded into neighboring buildings until his mish-mash of eleven buildings would engulf the Sixth Avenue blockfront from 13th to 14th Streets and around both corners.

Astoundingly, only two months after Levi's building plans were filed, the brick building on 14th Street was completed. On September 4, 1871 an announcement appeared in the New York Herald:

Albert Levi has removed from his old established stand, 321 Canal street, to the more centrally situated store, 56 West Fourteenth Street, where he will open on Tuesday, the 5th inst., under the firm of Albert Levi & Bro., with an entire new stock of fine watches, jewelry, sterling silver ware, &c.

By the last decade of the century, the district known as the Ladies' Mile was lined with lavish emporiums. The Sixth Avenue elevated, opened in 1878, conveniently transported women shoppers to the district. The former Albert Levi & Bro. building had become home to Rothschild's millinery and fancy goods store by 1893.

Nathan and Isidor Straus had controlling interest in Macy's at the time (Roland Macy had died in 1877). Like Macy, they continued to expand the massive Sixth Avenue store, adding two annexes on West 13th Street in 1892 and 1894. And they were not finished.

In April 1897, the architectural firm of Schickel & Ditmars filed plans for a $90,000, "nine-story-and-basement brick store" on the site of the old Albert Levi building for Nathan and Isidore Straus. The construction costs of this latest annex would translate to about $3 million in 2023.

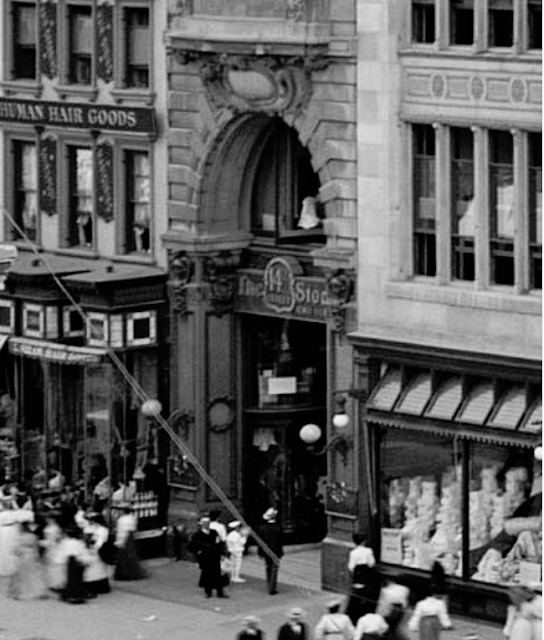

The slim limestone-clad structure--what would be called a sliver building today--was the tallest in the neighborhood. Its effervescent Beaux Arts style design included handsome carved angel heads above the storefront that flanked a panel announcing the store's name. The rusticated second and third floors featured a vast arched window and a French style balcony above a carved cartouche. Massive snarling lions' heads supported fruit-carved brackets beneath the ninth floor balcony. A copper cornice crowned the edifice.

As had been the case with Albert Levi's building, construction proceeded at a lighting-fast pace. On December 13, 1897, eight months after the plans were filed, an R. H. Macy & Co. advertisement in The Evening Post was titled "Christmas Presents for Everybody." It said in part:

Our New Entrance to the main store (open to-day) is another step of progress in our constant effort to improve our facilities and add to the comfort of our customers. It is at 56 West 14th Street and opens into our Newest Building, a beautiful and artistic addition to the architectural attractions of 14th Street.

The ad said that at the Macy Annex, "You can shop there all day with perfect comfort."

In June 1902, R. H. Macy & Co. hired the architectural firm of De Lemos & Cordes to do $50,000 in renovations to the West 14th Street building. (The architects had designed the massive department store building of Macy's greatest competitor, Siegel-Cooper, on Sixth Avenue in 1896.) The New-York Tribune noted that "new corridors and staircase are to be put in." The tremendous outlay is surprising, considering that in July 1901 R. H. Macy & Co. had announced it would erect a massive, 1.5 million-square-foot department store significantly north of the Ladies' Mile, on Herald Square.

On January 29, 1903 the New-York Tribune reported that Nathan Straus had sold 56 West 14th Street, "formerly the annex to R. H. Macy & Co's. store in Fourteenth-st.," to coffee importer Hermann Sielcken. Sielcken had paid "more than a million dollars" for the structure, or 32 times that much in 2023 dollars. "Mr. Sielcken said that he had no intention of using the building for his business," said that article explaining that he purchased the property as an investment. "The building is practically new and is one of the tallest buildings in West Fourteenth-st."

The article noted that Henry Seigel, R. H. Macy & Co.'s nemesis, intended "to erect a large drygoods store" on the site of the former Macy's main store. "He was asked last night if he would lease or had leased the annex, but he declined to talk on this matter." The secret came out two days later. The Chicago Tribune reported on January 31, "Henry Siegel authorized a statement to the effect that he had leased the ten [sic] story building running through from 56 West Fourteenth street to 55 to 61 West Thirteenth street, from Herman Sielcken, who purchased the property a few days ago." Siegel's 21-year lease came with the staggering rent of $70,000 per year.

Women in shirtwaists and exuberant millinery pass the former Macy's Annex around 1904. from the collection of the Library of Congress.

Ironically, a month later Herman Sielcken sold the building to the Fourteenth Street Realty Co. Two of its directors were Edmund E. Wise, a nephew of the Strauses and attorney for R. H. Macy & Co., and William W. Fitzhugh, the firm's auditor.

If Seigel originally intended to demolish all of the old Macy's properties, it never happened. Ruined by scandal, falsification of books, and misappropriation of company funds, he was imprisoned in 1914.

As the fashionable shopping district continued to migrate northward, West 14th Street became a center of lower-end stores. In February 1918, with World War I still raging, the U. S. Army's Quartermaster Department announced it would lease 56 West 14th Street "for distribution purposes."

Two years later, on October 17, 1920, The New York Times reported that Acker, Merrall & Condit had purchased and moved into the former Macy & Co. annex building. "More than $200,000 has been spent in remodeling the structure, and the firm's removal there is an important commercial change and addition to the one-time shopping section of Fourteenth Street," said that article.

Acker, Merrall & Condit had long roots, going back to a business founded in 1820. The firm imported luxury commodities, like fine wines, "fancy groceries," and cigars. The ground floor was leased to Kanter's Department Store, which dealt in a variety of goods from "gent's furnishings," to dry goods, shoes and furs. The store remained through 1926, after which a Sears, Roebuck & Co. branch occupied the space for two years.

Although it retained possession of the property, in 1931 Acker, Merrall & Condit relocated. The Hale Desk Company signed a ten year lease starting on May 1 that year for all but the ground floor space. The firm used the upper floors, where well-dressed women had once shopped for kid gloves and feathery hats, as an office furniture warehouse through 1939.

That year The New York Sun reported that the Noma Electric Corporation had purchased the building, calling it "an important transaction in the Fourteenth street section." Founded in 1925 by Albert Sadacca, the firm was an offshoot of his family's Christmas light manufacturing company, the National Outfit Manufacturers Association. Reorganized in 1953 as Noma Lites, Inc., it was reportedly the largest maker of Christmas lighting decorations in the world at one point. The firm remained in the building until its closure in 1965.

A close-up of the 1904 photograph shows the original first floor appearance and a panel placed over the Macy's sign above the entrance. (Note the little boy in the sailor suit.) from the collection of the Library of Congress (cropped)

The building next became home to TICO Plastics, here until 1971, and art book publishers Clarke & Way, Inc. which closed in 1970. The painted Macy's sign above the storefront survived, protected for some years by an added panel. By 2011, when the building was granted individual landmark designation, it was greatly faded, but still legible. Recently, however, the signage that had survived since 1897 was painted over.

Although the ground floor has been brutalized, the upper portion of the former R. H. Macy & Co. Annex building remains essentially intact.

photographs by the author

many thanks to historian Anthony Bellov for suggesting this post

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment