While the main entrance was centered on 50th Street, a second opened onto Fifth Avenue. from the collection of the New-York Historical Society.

In 1875, three years before William Henry Vanderbilt would begin construction of the three family mansions known as the Triple Palace on Fifth Avenue between 51st and 52nd Streets, George Kemp broke ground for a lavish residential hotel a block to the south. Because the Buckingham Hotel was to be a "family hotel" which did not accept transient guests, it was not considered a barbarous intrusion into the private mansion district. In fact, the same year that Vanderbilt began construction on the Triple Palace, Kemp started work on his own opulent mansion nearby at 720 Fifth Avenue.

The architectural firm of William Field & Son designed the eight-story, brick and stone hotel. Completed in December 1875, its design, a blend of Renaissance Revival and Second Empire styles, featured fully and segmentally arched windows, and unique stone quoins that resembled strap hinges. (The New York Times called the architectural style "Elizabethan.") The main entrance on East 50th Street sat within an imposing portico supported by paired, polished granite columns and fronted by a metal marquee. Directly above, were a series of three Palladian-style niches, one of which which held a gilded statue of the Duke of Wellington, and another the British royal coat of arms. Within the large swan neck pediment atop the cornice was an ornate cartouche emblazoned with the hotel's monogram.

On December 23, 1875, as finishing touches were being made, Gale, Fuller & Co., the proprietors of the Buckingham, published an announcement in The Nation, "to families desiring the best Hotel accommodation in a choice locality, having the most approved modern appliances for real comfort, privacy and perfect hygienic requirements." Interested families would have to pass muster for acceptance, the announcement noting, "personal application for accommodation" would need to be made.

The Hotel Buckingham opened on January 12, 1876. The Evening Express called it "one of the most imposing, beautiful and complete structures in the metropolis." The New York Times wrote, "this edifice may fairly be considered the result of the best efforts ever made in New-York to build a strictly first-class hotel for the use of families."

Families looked upon the white marble St. Patrick's Cathedral from their suites. image from Buckingham Hotel, Fifth Avenue, New York, 1877 (copyright expired)

The interiors had been designed and furnished by L. Marcotte & Co. of Paris. The Real Estate Record & Guide said, "They have made the Buckingham unique in all its various appointments and especially attractive to those who desire privacy, comfort and repose." The incidental elements--like tableware, linens and lighting fixtures--came from high-end dealers. The New York Times said, "Messrs. Arnold, Constable & Co., Tiffany & Co., the Gorham Company, W. & J. Sloan, L. Marcotte & Co., Mitchell Vance & Co. and Prof. Hylop [a ventilation expert]" had contributed to "make the hotel unique in its appointments and especially attractive to families who, before everything else, want the privacy and comfort of an elegant home."

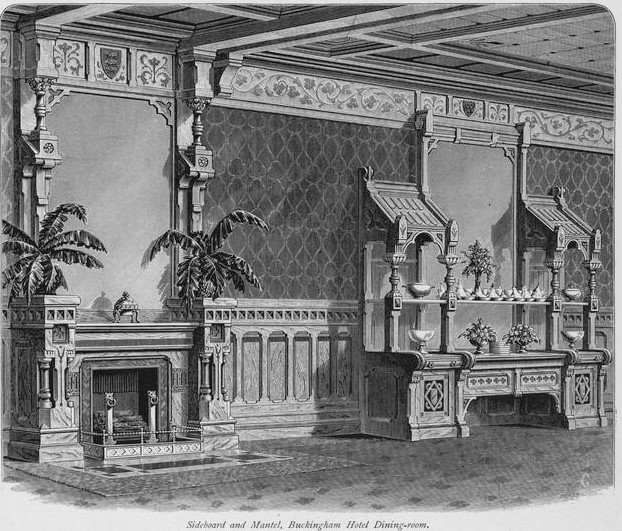

The grand dining room was designed in the Gothic style, its walls paneled in inlaid oak and "hung with a rich embossed leather, in the manner of the old stamped hangings of baronial antiquity," said the Record & Guide. The three-room ladies' parlors on the ground floor were in the Louis XVI style, in tones of "straw color, white, lilac, gray and gold." The gentlemen's parlors were "furnished with sumptuous seats and divans" in mahogany, according to The New York Times.

The main dining room had inlaid oak woodwork and leather wall coverings. from the collection of the New York Public Library

There were 150 white Italian marble mantles in the hotel. The New York Times said, "The entire upper part of the building is arranged for suites, but so connected that a family of ten or twenty may be as comfortably accommodated as a family of two." An advertisement assured the well-heeled residents that they could expect "no noise, no confusion of porters or waiters, no loungers or patrons of the bar who are not guests of the house. No attempt is made at mere display. The 'Steamboat' style is nowhere visible." In fact, there was "no public drinking bar on the premises," said an announcement, and "the smoking-room, which is splendidly fitted up, will be exclusively for the use of the guests of the hotel.

Among the initial residents was attorney George Whitfield Van Slyck. A descendant of an old Dutch family who came to New Amsterdam in 1640, he had left Williams College at the outbreak of the Civil War, organized a military company and served as its captain throughout the conflict.

Although the management of the Buckingham Hotel had firmly asserted that transient guests would not be accommodated, royalty made for an exception. Seven months after its opening, the hotel welcomed the Emperor and Empress of Brazil, Dom Pedro II and Teresa Cristina, and their eleven-member entourage. Included, according to the New York Herald, were "the Count and Countess of Bom Retiro, who are to accompany their Majesties to Europe, Donna Josephina da Costa, maid of honor...together with the male and female attendants of the suite."

On July 11, while her husband was visiting Tiffany & Co. and other spots, the empress "made an inspection of the kitchen and dormitories [i.e., servants' quarters] of the Buckingham and expressed pleasure at the cleanliness and order which she observed in them." Upon the emperor's return that evening, said the newspaper, he "dressed for the evening concert, which took place in the salon of the Buckingham." The article said, "The handsome parlors of the new hotel were crowded with ladies and gentlemen. The numerous gas jets lighted up the white walls of the Cathedral, that faces the hotel, and the scene was very brilliant."

When N. H. Tiemann & Co. produced this photograph in 1878, the Cathedral was still under construction. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York

Spending the winter seasons here from 1877 until 1884 were John D. Rockefeller, Sr. and his family. In his 2017 John D. Rockefeller, Jr., A Portrait, Raymond B. Fosdick wrote:

Although Mr. Rockefeller considered even the comfortable Buckingham Hotel ill suited for family life, it remained their winter home until his son John was almost eleven. They had a suite on the north side of the hotel looking out on St. Patrick's Cathedral. John [Jr]'s Grandmother Spelman and her daughter, "Aunt Lute," had another suite on the same floor, and the whole family ate their meals together in the main suite.

Eleven years after the Rockefeller family left the Buckingham, it would play a significant role in their lives. In the fall of 1895 Edith Rockefeller's wedding to Harold Fowler McCormick of Chicago had been planned to take place in the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church for months. The New York Times reported on November 27, the church "had been elaborately decorated for the wedding, according to designs made by the bride, and about 1,000 friends of the young couple had been invited to witness the ceremony."

The prospective groom was staying in his suite at the Buckingham Hotel, where The New York Times said, "Mrs. McCormick and her sons have had apartments for some time." Days before the wedding day, McCormick was afflicted with pleurisy. The New York Times wrote, "late Monday afternoon his physicians decided that the church ceremony must be abandoned." Cards announcing the change in plans were sent out and a man was stationed in front of the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church to intercept guests who had not received word.

The wedding took place in the McCormick suite on November 26. Harold McCormick appeared in the "main room" supported on the arm of his brother Stanley, looking "very pale." The New York Times said, "The ushers were already assembled in the drawing room awaiting the arrival of the bride and her bridesmaids. Although drastically scaled-back, the ceremony was elegant, the ushers and groom wearing frock coats, and the bride in "a superb gown of ivory satin, made in princess fashion, with a long round train."

Residents of the Hotel Buckingham rarely drew unwanted press. An exception to that rule occurred on March 23, 1894. Adrian Carl Pickhardt and Charles A. Martin both lived here. The Evening World said, "Messrs. Pickhardt and Martin are the sons of wealthy men, the former's father being a millionaire drug importer...Both he and Martin are members of several clubs." The young men, both about 27-years-old, went out together that night, ending up at Koster & Bial's Music Hall.

The Evening World reported that the pair, who were "dressed according to the very latest style, wearing light tanned shoes," had been drinking and "became boisterous" upon leaving. When Policeman Graven "expressed his disapproval of their conduct," he was told by Martin "to mind his own blank business." Martin was placed under arrest and on the way to the station house Pickhardt "rudely tripped Graven." He, too, was locked up in jail. The article said, "Pickhardt's father was sent for at the Buckingham, and he bailed both young men out." One can imagine the uncomfortable discussion that took place in the carriage back to the hotel.

A shocking incident occurred in the main floor café on January 14, 1907. That evening 22-year-old Harry E. Oelrichs, the son of Charles M. Oelrichs and a nephew of millionaire Hermann Oelrichs, was there with a friend. The New-York Tribune reported, "After being there about half an hour, a dispute arose between the waiter and Mr. Oelrichs, and before any one could prevent them the two were struggling on the floor." Waiters, bellboys and clerks ran into the café and finally separated the men. Before Oelrichs stormed out, he soundly kicked George A. Sloan. The 26-year-old waiter remained on the carpet, "suffering intense pain." He was carried to a bedroom where he lost consciousness. He was later transported to Flower Hospital where doctors said it would be several days before he could leave.

The next day Detective John D. O'Connor went to Oelrich's office and arrested him for felonious assault. The New-York Tribune reported, "Mr. Oelrichs was greatly surprised." He was bailed out of jail and his father later told reporters, "He is only a boy and there is really northing to it. He is just out of college, and from what I can learn it is merely a boy's affair. I have gone through the same experience myself." The article added, "At the Hotel Buckingham, no one would discuss the affair."

Major General Frederick Dent Grant, the son of President Ulysses and Julia Grant, and his wife Ida Marie Honore, had a suite on the fifth floor of the Hotel Buckingham in 1912. Grant was suffering from cancer and diabetes. Ida was awakened at 11:30 on the night of April 11 to her husband's "violent fit of coughing and choking." Grant was unable to tell her what was the matter. The Sun reported, "She tried her best to relieve him, but he rapidly became worse." Ida telephoned the desk to send for a doctor. Then, oddly enough according to the article, "she ran out into the hall weeping and crying, 'The old General's son is dying! The old General's son is dying!'"

At midnight, Frederick Dent Grant died of heart failure. The next day, as reported by The Sun, "Shortly before 3 o'clock the hearse drew up in front of the Buckingham and the body of General Grant was carried from the fifth floor of the hotel. Mrs. Grant, who was heavily veiled, followed, leaning on the arm of her son, Capt. Grant." Three coaches took family members, including Ida's sister, Bertha Palmer, the wife of millionaire Potter Palmer of Chicago, to the Battery behind the hearse. The body was taken to the chapel at Fort Jay on Governor's Island for his funeral.

On January 26, 1921 George W. Van Slyck, who had moved into the Buckingham Hotel upon its opening 45 years earlier, died in his apartments at the age of 78.

Had he not passed, the venerable lawyer would have had to find a new home before long. On July 30, 1922 The New York Times reported that demolition of the Buckingham Hotel would commence on October 1 to make way for the Saks & Co. department store. The article recalled:

The visitor entering its corridors and lobby was impressed, even in its later days, with its atmosphere of quiet and repose. It was a conservative hotel and its hallways never resounded with the bustle which was so characteristic of the old Fifth Avenue or the popular Hoffman House...Many of New York's best families lived there for years and to some it was a real affliction when the summons came to vacate.

The New York Herald said, "Other Fifth avenue hostelries were splendid, but the Buckingham was the haven of fashion and exclusiveness." It listed notable residents, including Admiral George Dewey, former Governor Charles S. Whitman (who was married in the hotel), Grover Cleveland and General Nelson A. Miles.

Sak's & Co.'s department store, designed by Starrett & Van Vleck, replaced the venerable hotel. photo by Epicgenius.

many thanks to reader Thomas Meara for suggesting this post

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

What's the connection between this and the Buckingham Hotel that then became The Quin?

ReplyDeleteThe name Buckingham was popular for hotels. They were in several cities and states, so I don't think there was necessarily any connection between these two.

Delete