image from The New York Mirror, 1829 (copyright expired)

On October 12, 1823, as the city expanded ever northward, members of three Episcopal congregations--Trinity, Grace and St. George's--joined to form a new parish that would be known as St. Thomas's. Among the founders, who included some of the wealthiest men in the city, were Charles King, William Beach Lawrence, and William Backhouse Astor.

Saint Thomas's Church was incorporated on January 9, 1824. The trustees quickly acquired an 80-foot wide plot of land within the former Herrick farm. Located at the corner of Broadway and Houston Street, it extended through to Mercer Street. According to The New York Times, the congregation paid $14,000 for the land (equal to about $456,000 in 2024). Six months later, on July 27, the cornerstone was laid.

The trustees had chosen one of the preeminent architects of the day, Alexander Jackson Davis. His Gothic Revival design for St. Thomas's Church would be patently Davis with two octagonal towers flanking a massive Gothic arched window below a stepped gable. The eaves along the sides were crenellated, another David hallmark.

Charles Burton's 1831 print reveals the handsome mansions that lined Broadway. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

The Mercer Street property behind the church was plotted into 58 burial vaults. An advertisement in the New-York Evening Post on April 12, 1824 offered,

Private VaultsThe Vestry of St. Thomas' Church offer to build Vaults for families, on their property the corner of Broadway and Houston streets. The terms may be known by applying toCHAS. KING, No. William-st.MURRAY HOFFMAN, 25 Pine-st. orRICHARD OAKLEY, 108 Front-st.

St. Thomas's Church, which stretched 118 feet along Houston Street, was completed in 1826. Saying it was "built of rough stones," Miller's Stranger's Guide to New York would describe it in 1866 as, "one of the earliest and best specimens of the Gothic." The Evening Post described the interior as being "chiefly of oak" including the "rich and finely carved oak furniture." The organ, according to the newspaper, was "one of the finest in the city."

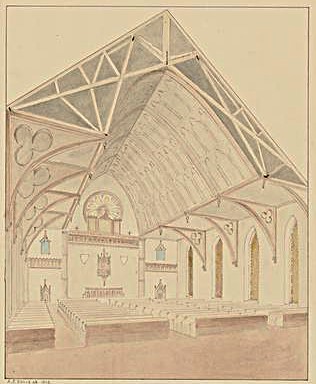

Alexander Jackson Davis's rendering depicts a rather simple interior with an oak ceiling. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

The church would be the venue of notable marriages and funerals, but perhaps none drew as much attention as the funeral of John Jacob Astor I on April 1, 1848. The Evening Post reported, "The procession left the house of his son, in Lafayette place, on Saturday afternoon, and passed on foot to St. Thomas's church." Astor's pall bearers were among the most influential men in New York City, including Washington Irving, Philip Hone, James G. King, James Gallatin and Judge Thomas J. Oakley.

"The coffin was of the richest mahogany, lined with lead," said the article, "and that lined with white satin, there being a square of plate glass over the face so as to allow those who wished to view the face of the deceased." Following the service, Astor's coffin was temporarily interred in William B. Astor's vault behind the church until "a suitable mausoleum should be provided" in Greenwood Cemetery.

George Harvey titled his watercolor of St. Thomas's Church "Night-Fall" from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

As he did every Saturday evening in the colder months, on March 1, 1851 the sexton lit the cast iron stove so the church would be warm for the morning's services. The New-York Tribune reported, "About 1 o'clock on Sunday morning, a fire was discovered in St. Thomas' Church, on the corner of Broadway and Houston-st. Before the firemen could reach the spot, the whole interior was in flames, and there is now nothing left of the time honored edifice but the bare walls."

The Evening Post said, "The alarm was immediately given, but too late to save the building...The walls, being of a massive structure, were but slightly impaired in their strength, with the exception of the tower on the north side, which has been considerably cracked by the intense heat."

By the time of the disaster, the district around St. Thomas's Church was no longer bucolic and residential. The New-York Tribune presumed that the church would not rebuild, but sell the property "and the proceeds applied to the erection of a new edifice further up town."

As the vestry considered its options, The Evening Post, sensing a public danger, demanded that the surviving portions of the building be demolished. An article on April 2, 1851 said in part, "The proper authorities should see at once to the removal of these ruins, before any damage is done to life and property."

Instead, however, the structure underwent a massive reconstruction. But the decision came with tragedy. Seven months after the fire, on October 7, 1851, The Evening Post reported that at about 11:00 that morning, a scaffolding on which four men were "at work in re-laying the wall of that edifice" collapsed. The workers plunged about 30 feet. "One man was instantly killed, and most shockingly mangled," said the article. "Another was so badly injured as to die before he could be removed to a place for treatment." The other two were less seriously injured and taken to a hospital in stable condition.

Miller's Strangers Guide to New York credited the blaze that gutted the interior with improving it. Its 1866 edition said the renovations resulted in "its present commodious and elegant internal appointments."

Despite the expense of restoration, less than nine years later, on April 21, 1860, The New York Times reported that the rector and vestrymen of St. Thomas's Church had applied to the courts to sell the property. Saying that the building was too small, the petitioners said it "will seat only about one thousand persons." A significant impetus, no doubt, was the increasingly commercial and rowdy neighborhood.

Already, however, there was a conflict within the congregation. "A number of the property-holders and vault-owners," said the article, "oppose the movement, alleging that more than half of the congregation reside below Fourteenth street."

In 1865, St. Thomas's Church (left) sat amid a bustling, congested Broadway neighborhood. from the collection of the New York Public Library

The discussion went on for five years. Then, on August 2, 1865, The New York Times reported that the property "has been sold to a large clothing-house in Broadway for the sum of $175,000." The deal included the caveat that the building "is not to be removed until May 1866, when the site will be occupied as a store." The transaction did not entirely solve the problem of the vaults, however, which were not included in the sale. "The remains of the Astors were, at a comparatively recent date, removed and laid in Trinity Cemetery; and it appears that similar action has been taken by many vault-holders," said The Times. Nevertheless, six stubbornly refused to move their families' remains.

A month later, the vestry announced it had purchased the northwest corner of 53rd Street and Fifth Avenue as the site of its new structure. The New York Times said, "It is supposed...that Upjohn & Co. will be employed as architects." The supposition was correct. The cornerstone to the new St. Thomas's Church designed by Richard Upjohn and his son, Richard Mitchell Upjohn, was laid on October 14, 1868.

By then, Alexander Jackson Davis's solid stone structure had been gone for two years as the congregation shared space in another church. On June 12, 1866, The New York Times had reported, "The demolition of St. Thomas' Church, at the corner of Broadway and Houston-street, which was commenced a few weeks ago, is now nearly completed, and scarcely one stone of the edifice remains upon another." (The six families who had held out on removing the remains in their vaults, had eventually capitulated.)

.png)

At what quadrant of the Broadway-Houston intersection was the church located?

ReplyDeleteNorthwest corner, site of the Cable Building today.

DeleteWilliam Beach Lawrence built the nearby 498-500 Broadway in 1858 on the site of smaller buildings built by his father Isaac Lawrence (prominent merchant and banker) in the 1820s. Their family owned the property until the 1940s.

ReplyDelete