In the 1890's the sumptuous mansions of West End Avenue rivaled those of Riverside Drive and West 72nd Street. At the turn of the century, the two residences at 557 and 559 West End Avenue were purchased by the New York Protestant Episcopal Public School (a corporation of Trinity Church). On July 19, 1902 the Real Estate Record & Guide said the houses were "proposed to be used by them as a girls' school." The plans were to join the residences internally, alter walls, "fill in staircases between the pantries, and to strengthen floor timbers."

The alterations were completed by fall, and on September 16, 1902 an advertisement appeared in the New-York Tribune that read: "St. Agatha--Church School for Girls. 557 and 559 West End Avenue, New York City. Elementary and High School. College Preparation. Gymnasium."

The altered mansions apparently did not work out as the trustees had hoped. In 1907 the houses were demolished along with the one next door at 555 West End Avenue, and architect William A. Boring was commissioned to design a substantial school building on the site. His English Collegiate Gothic structure would rise seven stories above a basement level, surrounded by a light moat. Above the limestone base, deep red brick was diapered in a subtle diamond pattern. Boring hinted at the academic purpose of the building with carved, open books at the second through fourth floors, and spread-winged owls (symbols of wisdom) below the buttresses at the fifth. The crenellated octagonal towers that flanked the stone parapet added to the Gothic motif.

St. Agatha's Church School remained in the building for nearly four decades. In 1941 Trinity Church sold the property to the New York Roman Catholic Archdiocese. The new owners spent $150,000 to renovate the structure (about $2.6 million today) to convert the former female-only school to the male-only Cathedral College.

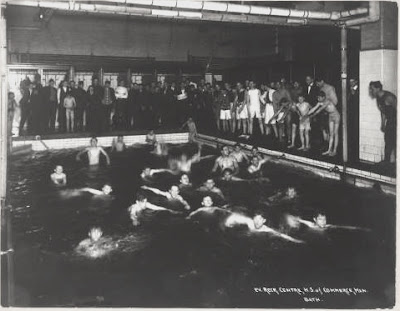

Cathedral College had been founded in 1903 at 462 Madison Avenue. Students in the renovated building would receive four years of high school and two years of collegiate studies. On September 8, 1942, The New York Times reported, "The new building contains a library, a chapel, laboratories, an elaborate gymnasium, cafeteria and administrative offices." Its president, the Very Reverend John J. Hartigan said the building was "fully adequate for its purpose of educating boys intending to enter the priesthood."

Eighth grade boys hoping to attend the school were required to pass a test. A notice in The Monroe Gazette on January 26, 1964 announced in part, "Any boy of good character and intelligence, graduating from either public or parochial schools in June 1864, who feels he has a vocation to the diocesan priesthood, should take this examination." The notice cautioned, "Each applicant should bring with him a letter of recommendation from his pastor."

A horrifying tragedy happened to one student on July 2, 1978. Hugh B. McEvoy was 16 years old and had just finished his sophomore year. He was sitting on a railing in front of Teachers College at Columbia University with 15-year-old Peter Mahar at around 10:00 that night, when two boys approached and asked him, "What are you laughing at?"

Mahar said, "We're not laughing at anything," but one of the boys pulled out a small-caliber revolver, put its muzzle to McEvoy's forehead, and shot him. Hugh McEvoy lingered in a coma for four days before dying at St. Luke's Hospital. The two suspects, 13 and 16 years old, were arrested three days after the murder. At a press conference held in Cathedral College, Hugh's father, Leo McEvoy, said "My faith in religion is one of forgiveness, turn the other cheek...but it's not easy to do."

As fewer young men had a vocation for the priesthood, the halls of preparatory seminary schools in the 1980's were greatly empty. In closing the Cathedral Preparatory Seminary in Brooklyn on May 3, 1985, a Diocese spokesman pointed out that now "The larger New York Archdiocese has only one, at 555 West End Avenue, at 87th Street."

And Cathedral College would not survive much longer, either. In 1991 it was closed and St. Agnes Boys' High School moved into the building. The school had operated for decades on East 44th Street, near St. Agnes Roman Catholic Church.

In 2007 there were 320 students in St. Agnes Boy's High School. Tuition was $3,400 per year, and Michael J. Leahy, in his If You're Thinking of Living In..., said that many of the the boys "are from immigrant families, and more than 85 percent of graduating seniors go on to higher education."

But parochial schools were having trouble surviving, as well. The diocese permanently shut the doors of St. Agnes Boy's High School in 2013, and the following year developer and architect Cary Tamarkin purchased the building for $50 million. Ironically, the structure that once prepared young boys for a life of holy poverty, now contains luxury apartments, the largest of which, at six bedrooms and 8,429 square feet, has a price tag of $42 million.

photographs by the author

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)