The Architectural Record, January 1903 (copyright expired)

With commercial buildings moving ever northward, the private brownstone houses along 42nd Street were rapidly being demolished and replaced in the last years of the 19th century. On March 28, 1900, Daniel E. Seybel purchased the two five-story houses at 5 and 7 East 42nd Street from Daniel B. Freedman and Frederick J. De Peyster, respectively. The New York Times commented, "Mr. Seybel declined yesterday to say anything further about...the future of the property."

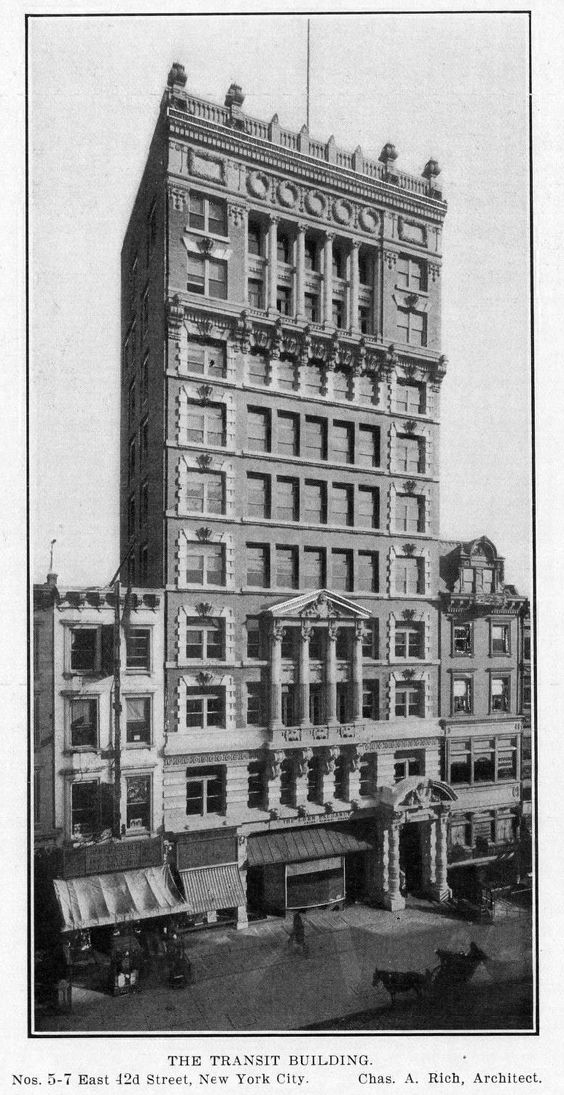

Seybel quickly resold the parcel to Joseph Milbank. On May 20, the New-York Tribune reported he planned a 10-story office building to be called The Transit Building, on the site. The article noted there would be two stores at street level, "one large and one small." The larger store, the writer added, "will be lighted by a larger interior court. The rear part of the store is divided into two stories, giving private offices and a cash department."

Milbank had hired architect Charles A. Rich to design the building. Until the previous year, he had been partners with Hugh Lamb in the prolific firm Lamb & Rich. His frothy, limestone, pink brick, and terra cotta design would be called by the New-York Tribune, "in the French classic style." Today, for the most part, it would be deemed Beaux Arts.

The entrance to the upper floors would be within an impressive portico with free-standing banded columns. It led to a circular rotunda lined "with marble and glass mosaic." A mezzanine was "shut off from the main hall by a heavy ornamental screen of pierced marble work." The upper floors would hold office rental office space, other that the two topmost which had "roof apartments, with rooms for the janitor and help."

Exactly why Milbank christened it The Transit Building is unclear, as he had no tenants involved in transportation. When the Corn Exchange Bank leased the large ground floor space in November 1901, the Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide noted, "This 10-story building is now fully rented."

It became a favorite of builders and architects. Among the early tenants were architects A. J. Manning, W. G. Pigueron, and Mulliken & Moeller. Construction firms like George H. Pigueron, William Crawford, and the Murphy Construction Co. were also early occupants.

This firm was among the construction-related firms in the building in 1901. Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide, December 28, 1901 (copyright expired)

The National Association of Automobile Manufacturers took offices in 1903. It was the dawn of the automobile era, and while there were already 495 automobile makers in America, it would be another three years before Henry Ford revolutionized the industry with his Model N, the first generally affordable auto.

A conference was held in the National Association offices on January 25, 1908, to "discuss rules and plans for the coming Glidden Cup tour," according to the New York Times. The race had been held since 1904, sponsored by the American Automobile America. The article said, "The plans for the next big tour were discussed for over four hours, every detail being carefully gone into."

Named after banker and automobilist Charles J. Glidden, the Glidden Cup Tours had officials called "checkers," who used checkered flags to identify themselves--the seed of today's checkered flags that indicate the end of the race.

The William J. Taylor Company was one of the several contractors that remained in the building for years. Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide, December 18, 1909 (copyright expired)

Unrelated to either construction or automobiles was publisher George H. Daniels, in the building by 1905. While the title of the firm's magazine The Four Track News suggested racing, its articles covered travel, biography and literature.

Milbank's venture had proved so successful that in 1914 he purchased three houses behind the Transit Building, on 43rd Street, and hired George B. Post & Sons to design a 10-story annex. The New York Times, on May 3, explained, "it will be connected with the Transit Building by an arcade hallway on the ground floor." With a much simplified design, it was completed the following year.

By the first years just preceding World War I, the architects in the building had been joined buy the offices of Peck & Brown, William Keegan, and Kovalsky Bros. Another automotive-related firm in the building was Mayo Radiator Company, headed by Virginius St. Julien Mayo.

An electrical engineer, Mayo held seven patents on various inventions. His successful business provided him an annual income equal to more than $2.5 million today and afforded him and his wife, Wilhelmina, a luxurious lifestyle in a fine home in Brooklyn. But what Wilhelmina did not know was that Mayo had a second home in New Haven, Connecticut and a second "wife." It was a tangled, romantic web.

In fact, although they presented themselves as man and wife, Mayo and Wilhemina Meyer had never married. Mayo shared the New Haven mansion, with its four servants and four automobiles, with his stenographer, Lillian May Cook, whom he also introduced as Mrs. Mayo--but whom he had not married, as well. The web of deceit fell apart following Lillian May Cook's suicide in February 1915. Wilhemina sued Mayo for $250,000 (more than $6.4 million in today's money) for damages.

Before Wilhemina's suit was decided, more skeletons fell from Mayo's closet. On March 12, 1915, The New York Times reported that Susie M. Wahlers, an office staff member in the company's New Haven plant, had sued him "for the support of her two-year-old child and for damages." And there seemed to be a third "wife," as well. Simultaneously, the town prosecutor was "awaiting word from Mrs. Florence Mayo of Scranton, Penn...concerning the marriage of Mayo at Binghamton in 1890."

Susie Wahlers told a reporter about her Lothario boss:

Mr. Mayo was a fascinating man. He used to keep me at work late in the evening. I fell under his influence. I am not a bad girl, and I have suffered terribly for what I have done. When I told Mr. Mayo what had happened, he wanted to have me married to a young man of my acquaintance. His insinuations were false, and I would not let him escape his responsibility.

In 1917, a change in the typical Transit Building tenant came in the form of the Drama League. The first meeting that year had to do with "The Theatre During the War." Among the items discussed, according to The Sun on November 25, was the League's fund "for entertainments for the soldiers in the training camps."

Another tenant strongly behind the war effort was the newly-formed Volunteer Motor Transport Committee. The group offered its services to the War Department in organizing volunteer motor companies, researching roads for military purposes, "especially with regard to their ability to carry heavy motor traffic," said the New-York Tribune on April 22, 1917, and the recruitment of drivers and mechanics.

While the headquarters of the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce was in the building by war's end, the entertainment business was heavily represented as well. In 1919 Theatre Arts Inc. was here. The firm published the quarterly Theatre Arts Magazine. The smaller ground floor shop was home to the Drama League Book Shop.

Each year the Drama League held a dinner to present awards--more or less the precursor to today's Tony Awards. But in 1921 it had a problem. Charles S. Gilpin had wowed audiences and critics with his masterful performance in Eugene O'Neill's The Emperor Jones at the Princess Theater. Everyone agreed that Gilpin's performance ranked him as the best actor of the season. But Gilpin was Black.

Charles S. Gilpin in his role in The Emperor Jones, Theatre Magazine, January 1921 (copyright expired)

On February 16, 1921, the New-York Tribune wrote that the Drama League had received "letters registering a positive kick against including Gilpin in the list of ten." The solution was cloaked in racial sympathy. "With keen logic, the Drama League...ruled that Gilpin should not be included among the dinner guests, because his acting, although distinctive, had shown his own race to bad advantage, and therefore was not in his favor, and also because, if he were invited, he probably would not attend, so what would be the use of inviting him?"

Tenants in the building continued to gravitate towards the arts. on March 18, 1923 The Morning Telegraph reported, "A new orchestra has been formed by a group of American musicians and music-lovers--a new symphony orchestra of American-born players and an American-born conductor." The American National Orchestra was "American in the fullest sense," said the article. Its business headquarters were established in the Transit Building.

In 1932 the Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank took over the large street level space from the Corn Exchange Bank. The bank modernized the lower facade, doing away with Charles A. Rich's outdated design in favor of a sleek Art Moderne front.

At the time contractors and architects continued to share the building with entertainment firms. The Thomas O'Reilly construction business would remain at least through 1939, and in 1938 the Wyckoff-Morris Modernization Plan was organized here. On March 12 The New York Times said, "The concern will specialize in modernization projects on a contractual basis."

Architect Harry B. Rutkins received unwanted visitors at his office in the Transit Building on July 24, 1936 in the form of police officers. Five days earlier a building he had designed had collapsed during construction in the Bronx. Eighteen men were killed. The 33-year-old architect was taken from his office in handcuffs, charged with manslaughter in the second degree.

The building as it appeared in 1949. photo by Wurts Bros., from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

In the mid-1940's the National Republican Vigilance Committee was headquartered here. Over the subsequent decades the office building was little changed, outwardly. It survived until 1967, replaced by Emigrant Bank's 26-floor steel and glass tower.

LaptrinhX.com has no authorization to reuse the content of this blog

.png)

Did this building ever contain apartments? I have an ancestor who listed 7 E 42nd St as a residence in 1924.

ReplyDeleteNot officially, although there may have been a caretaker's apartment or some similar accommodations.

Delete