Born in 1830, Henry Astor was the youngest son of William Backhouse and Margaret Armstrong Astor. He incurred the wrath of his family at the age of 20 when he married Malvina Dinehart. She was the daughter of a farmer and gardener who lived near the Astor family's summer residence at Red Hook, New York. He had done gardening work on the estate.

Henry and Malvina moved to West Copake, New York. Most New Yorkers assumed that his disobedience resulted in his ruin. Decades later The New York Times remarked, "It was thought for years that he was a pauper, disinherited for marrying the gardener's daughter." Instead, he and his wife lived well on "the rents from property in the heart of New York City, valued at many millions." It was held in trust, however, and Henry was kept at arm's length from his holdings. The newspaper added, "The trust established for Henry Astor was recommitted in 1869 to his brothers, John Jacob Astor and William Astor."

A portion of his 119 parcels of real estate was "the block bounded by Broadway, Eighth Avenue, Forty-fifth and forty-sixth Streets." In 1874, the Astor trust leased plots on West 46th Street to developers James Henderson and James Blackhurst, who erected a long row of 20-foot-wide, brownstone-fronted Italianate houses. They advertised the completed residences for sale on April 25, 1875, clearly noting, "On Astor Lease."

No. 342 was sold to John Russell. Neither he nor his son, Robert, listed a profession in city directories, suggesting they were possibly "gentlemen," meaning they lived off inherited money. The Russell family maintained a 218-acre summer estate in Dutchess County.

The family's residency was very short lived. By 1877 the home was operated as a Jewish boarding house. An advertisement in the New York Herald on September 16 read:

Wanted--One or two Jewish gentlemen in a first class private boarding house; location and accommodations unexceptionable; charge moderate.

Unlike today's connotation, the term "unexceptionable" in 1877 assured the reader that no exceptions, or faults, could be found. Among the boarders in 1878 and '79 was Samuel Lewison, who was attending New York City College.

Edwin C. B. Garsia moved his family into 342 West 46th Street in 1879. A stock broker and consul with offices at 14 Broadway, he was born in Kingston, Jamaica and had arrived in New York City in 1861. Six years later he married Maria Gertrude Bachem. The couple had two children, Maria and Edwin Rudolph Christopher, (known as Teddy).

Garsia's work seems to have necessitated significant travel. He was occasionally listed on the manifests of steamships headed to places like England and the Dominican Republic without his family.

Even well-to-do families often took in a boarder and in 1883 French-born Eugene Lebou was living with the Garsias. Lebou's wife of 16 years had left him, resulting in his being emotionally troubled. He became obsessed with getting his wife back, the New York Herald saying that he "was at one time in the express business, but had abandoned his place and work for drink."

In what today is known as stalking, Lebou doggedly trailed his wife. The situation became so serious that on August 24 she went to the police, complaining "that he was following her about and was the cause of her losing several positions." Police began searching for Lebou to arrest him. He seems to have gotten word that he was a wanted man. The following day he hired a rowboat at 72nd Street, rowed out into the Hudson River and jumped overboard and drowned.

The Garsia's social status was evidenced in 1892 when society columns noted, "Mrs. Garsia and Miss Garsia are at home on Fridays in February."

After nearly two decades in the house, the Garsia family left in 1894. It became home to Adolf Bottstein and his family. Born in Poland, Adolf and his wife, the former Augusta Ollendorf, had seven children. The rent on the leasehold, or lot upon which the house stood, that they paid to the Henry Astor trust would equal about $1,000 per month today.

Like the Garsias, the Bottsteins were involved in society. On April 23, 1897, for instance, the New-York Tribune reported on the upcoming "springtide jubilee" at the Lexington Opera House. The article noted, "Tickets may be obtained upon application to Miss Louise Bottstein, No. 342 West Forty-sixty-st."

During the winter of 1904 Frederic Bottstein caught a cold, which developed into pneumonia. The 31-year-old died in the West 46th Street house on January 19, 1905. His funeral was held in the parlor three days later.

By 1910 the Bottstein family had left West 46th Street, and the house was being operated again as a boarding house. By now the neighborhood had seen major change. One block to the east the former Longacre Square had been renamed Times Square in 1904 and was quickly becoming the center of the entertainment district. The residents of 342 West 46th Street were now working class.

Typical was Thoams Bisping, described by The Sun in 1910 as the "uniformed chauffeur" of a taxicab. Bisping went through a terrifying ordeal on February 24, that year. He told police he "got a call at the Cafe de l'Opera from a man who said over the telephone, 'This is the Senator." Bisping picked up the man, who never gave his real name, then made two more stops until there were five passengers in his cab. He drove them to Bunt Gilmartin's saloon at Eleventh Avenue and 37th Street where they ambushed a known gangster, Jacob Greenthal, known as Sheeny Jake.

The men stabbed Greenthal on the sidewalk. "The thing was done in broad daylight," reported The Sun, noting it was witnessed by Bisping, "who saw the whole performance, but was too scared to move or speak." The assailants climbed back in the cab, "and drove to Ninth avenue and fortieth street, where they paid for their ride and walked off." The article said, "As soon as Bisping was sure his five fares had vanished for good he went to a telephone and called up Police Headquarters."

Henry Astor died on June 7, 1918 at the age of 88. The estate began selling off the properties soon afterward. Like almost all of the houses along the block, 342 West 46th Street continued to be operated as a rooming house.

The proximity of the 1875 row to the theater district made the properties attractive to restaurant owners. In 1929 the basement level of 342 West 46th Street was converted for a restaurant. It was home to A La Fourchette by 1935.

Four decades later the French restaurant was still going strong. On March 30, 1973 Raymond A. Sokolov, writing in The New York Times, said, "Survival is not the only recommendation for an eating place, but it is a good one." He wrote, "It is neither grand nor a museum of cookery, but it is a very professional place and the price remains competitive, although no longer quite the bargain that it once was."

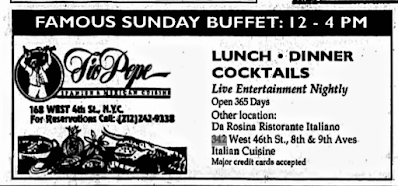

By the early 1990's A La Fourchette had been replaced by Tio Pepe, a Spanish-Mexican restaurant. In 1994 Da Rosina Ristorante Italiano opened, and remains in the space today. In the meantime, above the basement level the house is vacant and boarded. The brownstone framing of the entrance is crumbling and iron supports appear to stabilize the stonework of the upper floors--a sad circumstance for a once proud residence.

photographs by the author

no permission to reuse the content of this blog has been granted to LaptrinhX.com

.png)

Hello, I found a matchbook from this location and have quoted your blog in my post. Please let me know if you would like me to remove the copy. https://www.instagram.com/p/DDw9mT4OorG/?img_index=1

ReplyDeleteperfectly fine!

Delete