Cousins John Eliot Condict and Samuel H. Condict were both highly successful. John was the principal in J. E. Condict Co. with his brother, Silas B., makers of leather "cavalry cartridge boxes, cap boxes, &c.." He was also vice-president of Condict & Co., brokers in railway stock. Samuel ran S. H. Condict Co. manufacturers of saddlery and military accouterments. Samuel ran S. H. Condict & Co., which also manufactured leather accessories.

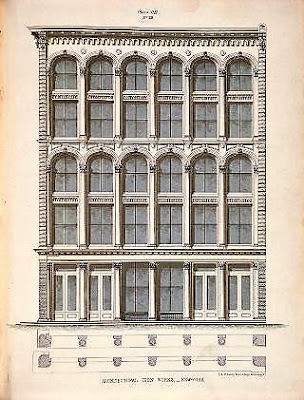

In 1860 the cousins began construction of the new headquarters for their businesses at Nos. 55-57 White Street on the site of two old structures. Designed by the prolific architectural firm of John Kellum & Sons and completed in 1861, it sat on the corner of Franklin Alley (later given the more decorous name of Franklin Place). At the time cast iron facades were rapidly coming into fashion. The innovation enabled rapid construction, lowered building costs and was touted as fireproof. Kellum turned to Daniel D. Badger's Architectural Iron Works to fabricate the facade. It appeared in the founder's catalog four years later.

|

| Architectural Iron Works New York, 1865 (copyright expired) |

The facade featured a few unusual elements--the side piers of the ground floor pretended to be vermiculated stone blocks. They morphed into highly uncommon diamond-point quoins on the upper floors. A handsome corbel table ran below the elaborate cornice. The cast iron design was inspired by earlier stone versions, most notably in its two-story "sperm candle" columns, so-called because of their similarity to the thin candles made from sperm whale oil. In fact, two years earlier Kellum and his former partner, Gameliel King, had designed a highly similar building in marble at No. 388 Broadway

|

| Kellum clearly borrowed elements from his earlier marble building for the Condict building. |

Both D. E. Condict & Co. and S. H. Condict & Co. moved in, along with commission merchants Sprague, Colburn & Co. John E. Condict was more than a landlord to John H. Sprague. The two were long-time friends outside of business.

The same year the building was completed the first shot in the Civil War was fired. The national crisis was a boon for both Condicts who landed military contracts. During the first year of the war S. H. Condict & Co. supplied the Government with $10,324 worth of gun-slings, cartridge boxes and other "equipments." That amount would equal about $165,000 today.

The cost-efficient firm did not waste its remnants. On December 22 1861 it advertised: "To Shoe Manufacturers--A large lot of small pieces of Leather for sale, suitable for shoe manufacturers. Apply at 57 White street, to S. H. Condict & Co."

J. E. Condict & Co., too, sold to the military. During the fiscal year of 1865-66 The Government purchased $3,187.67 in "horse equipment" (about $50,000 today). The business relationship with the military lasted beyond the war. In May 1873 S. H. Condict & Co. placed a bid with the United States Navy for $5,32.50 in knapsacks.

Sprague, Colburn & Co. remained in the building following the death of John H. Sprague. Shockingly, John Eliot Condict saw opportunity in the death of his close friend. He approached Sprague's widow, Henrietta, and offered to help administer her finances. The American and English Railroad Cases later reported "J. Elliot [sic] Condict had long been a friend of her husband, doing business in New York in railway securities, under the style of 'Condict & Co.'"

In February 1870 Henrietta loaned Condict $25,000, taking his note in exchange. Just before it became due, he suggested she buy $75,000 in bonds of the Madison & Portage Railway Company from him. Condict put the $25,000 he owed her toward the purchase. When she had received no interest by April 1879, she placed control of her affairs in the hands of John M. Whiting who dug into the matter. No evidence could be found that the railroad had ever received payment for bonds in the name of Henrietta A. Sprague. A law suit followed which found Condict liable to return the funds, with interest, to Mrs. Sprague. It may have been the publicity and humiliation that caused Condict to move his family to San Francisco that year.

In the meantime Sprague, Colburn & Co. continued to represent manufacturers in its White Street showrooms. In 1879 it sold the "dress goods, handkerchiefs, tie silk and grenadines" of Dohery & Wadsworth; and the silk goods of Jersey City makers Victory Silk Mills; Field, Morris, Fenner & Co.; and A. Pocachard.

In the 1880's two major firms occupied the building. Commission merchant J. H. Libby & Co. was founded in Maine around 1838. It opened its New York office in 1863. The firm handled woolens and "domestic mixed goods of fine grades." In 1888 Illustrated New York: The Metropolis of To-day commented "The business premises in this city are spacious in size, eligible situated for trade purposes, and are at all times stocked to repletion with new, reliable and valuable goods."

Also in the building was Lawson Brothers, importers of "laces, embroideries, curtains &tc." Founded by Robert Lawson in 1858, it now engulfed three floors of Nos. 55-57 White Street. Illustrated New York said of the firm, "This house has long been recognized as among the most extensive importing houses in this line in the country, possessing every facility for keeping itself en rapport with the most famous of European manufacturers."

H. J. Libby & Co. would remain in the building at least through 1906; while Lawson Brothers left around 1896. In its place was Campbell & Smith, merchants in cloaks, millinery, notions, fancy goods and hosiery.

By 1906 The American Mills Company had taken over the Campbell & Smith space. The firm manufactured "elastic fabrics, elastic webbings, suspender and garter webbings, elastic braids and suspender braids" in its Waterbury, Connecticut factory.

Hoffman-Corr Manufacturing seems to have been the sole occupant of the building by 1908. The firm manufactured seemingly disparate products: rope and twin, "cotton waste and candle wicking," and flags.

Factory work in the early 20th century could be tedious and discouraging. Many firms promoted morale by sponsoring company baseball teams, bowling teams and other activities. On August 23, 1908 the New-York Tribune reported "The Commercial Athletic Association has set apart the afternoon and evening of August 29 for its grand carnival and athletic games, which are to be confined wholly to the members of the houses represented in the baseball league." Among them was the Hoffman-Corr Manufacturing Company.

A massive two-week celebration of the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson's discovery of the Hudson River and the 100th anniversary of the invention of Robert Fulton's successful steamboat was held in New York from September 25 to October 9, 1909. Hoffman-Corr Manufacturing responded by producing "bunting flags," purported to be exact reproductions of the flag that flew on Hudson's Half Moon in 1609.

|

| The Country Gentleman, August 26 1909 (copyright expired) |

Two years later Clough, Pike & Co., importers of "mohairs" shared the building with Turtle Bros., importers of linens. Both were foreign-based. Clough, Pike & Co.'s mills were in Bradford, England; while the headquarters of Turtle Bros. was in Belfast, Ireland.

Harry T. Turtle handled the American operations, while Herbert S. Turtle oversaw the Irish side of things. The well-respected firm suffered embarrassing press when Harry T. Turtle was arrested on the afternoon of June 6, 1912. The bold headline in The Evening World read: Linen Importer Held, Accused of a $100,000 Fraud." Special Treasury Agents Williams and Coffee had been surveiling Turtle since January 1910. He was charged with defrauding the Government by undervaluing imported goods.

|

| The Dry Goods Economist, January 13, 1917 (copyright expired_ |

Turtle Bros. was still in the building in 1919, a year after Herbert S. Turtle died. But it was gone by the following year.

In 1920 the building was shared by hospital linens manufacturer Geo. P. Boyce & Co., and cotton and woolen goods jobbers Louis Bralower & Sons.

The building was sold in January 1922 for $140,000; about $2 million today. The timing could not have been worse for the buyer.

On February 21, 1922. Brothers Charles, William, Harry and Hyman Bralower were about to close up at around 6:00 when smoke was seen coming from the basement. While they attempted to find the source, an automatic fire alarm sounded, bringing 15 pieces of fire equipment to the scene.

The New-York Tribune reported the firefighters found "more than 1,000 tons of baled cotton on fire in the sub-cellars." The heat was so intense that they could not enter. "Instead they chopped holes through the sidewalk and poured tons of water into the cellar," according to The New York Times. The acrid fumes forced the firefighters to work in shifts; but even that did not save 12 from being overcome. Department physicians on the scene treated the men.

While a crowd of 5,000 spectators gathered, according to the New-York Tribune, the fire "spread to the main floor of the building and were rapidly penetrating to upper floors by air and elevator shafts."

Additional alarms brought a total of 18 companies. Two hours after the fire broke out two complete companies of firefighters were still inside the ground floor, "trying to save large quantities of baled cotton goods," said The Times. Chief Crawley suspected that by now the floor was unsafe and ordered the men out "They had no sooner got to the street when the floor fell with a roar, carrying everything on it into the flames below."

It took firefighters three hours to extinguish the blaze, which caused damages equal to $2.9 million today. But Daniel Badger's fireproof iron facade had proved to be just that. While the interior of the building was severely damaged, the exterior needed new windows and a coat of paint.

Leather manufacturer M. Slifka & Sons moved into the rebuilt structure in 1923. The firm made and exported purses, belts, wallets, and leather suspenders for military use.

Despite the recent substantial repairs, architects Schwartz & Gross were commissioned in 1929 to do a general renovation. The changes resulted in a store and offices in the first floor, offices in the new mezzanine level, a stockroom on the second, and factory space above.

By the last quarter of the 20th century the Tribeca renaissance had reached Nos. 55-57 White Street. In 1982 the Collective for Living Cinema was in the building; and in 1986 the ground floor itself became a piece of art. Artist Karen Zuegner used the three central windows as a show entitled "Fragments of Life." She filled each 10-foot high window with three-dimensional geometric forms in blacks, whites, and grays. The New York Times critic Grace Glueck explained on April 25, "Their arrangement--representing her life--is helter-skelter, playing off the flat, orderly two-dimensionality of the glass surfaces, though a grand triumphal arch in the middle window pulls the whole tableau effectively together."

The gentrification of Tribeca brought threats to its historic architectural fabric. On September 9, 1988 New York magazine reported "TriBeCa residents are outraged over a developer's plan to build a 33-story condominium tower--including a 9-story addition atop an 1861 landmark cast-iron building." Virginia Millhiser proposed to demolish the five-story synagogue at No. 49 White Street and replace it with a tower, the base of which would form a bridge over Nos. 55-57 White. The problem for locals was that the "1861 landmark" wasn't.

The civic groups prevailed, lobbying the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate the Condict building an individual landmark. Millhiser's project was successfully stifled.

Two years later the upper floors were converted to apartments. The restoration of the facade and the fabrication of historically appropriate doors resulted in the building's return to its striking mid-Victorian appearance.

photographs by the author

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment