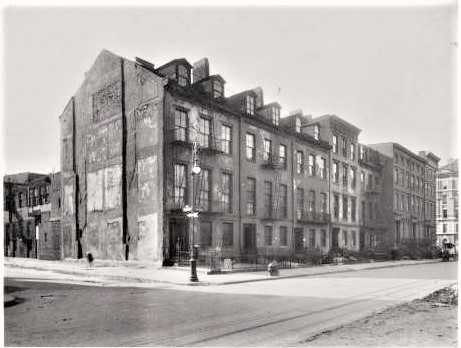

The extension of Sullivan Street to Washington Square resulted in the unsightly eastern wall, seen in this 1922 photograph. from the collection of the New York Public Library

In 1826 Mayor Philip Hone proposed renovating the large burying ground in Greenwich Village to a military parade ground, to be called Washington Square. The thousands of unmarked graves, as many as 20,000 of them victims of them of the 1822 yellow fever epidemic, were essentially disregarded.

Two years later construction began on the grand George Rogers mansion on the north side of the park. The first residence on Washington Square, it would not stand alone for long. By the mid-1830's the park was ringed by elegant marble-trimmed brick homes that made a Washington Square address as enviable as one in the exclusive Bond Street and St. John's Park neighborhoods.

While those along Washington Square North were designed in the Greek Revival style, their counterparts along the southern hem were Federal, with peaked roofs and prim dormers. Three-and-a-half stories tall and 25-feet wide, their entrances sat above short stoops. Full-width iron balconies fronted the floor-to-ceiling second floor windows.

By the early 1860's No. 47 Washington Square South was home to the family of Dr. Alvin M. Woodward. They remained until 1869 when the widowed Harriet Runnett moved in with her adult son, William H., who was president of the New York Academy of Music. William may have been living with his mother because of health problems. On June 17, 1871 he died "after a lingering illness," according to the New York Daily Herald. His casket was placed in the parlor awaiting his funeral four days later.

It may have been her son's death or the plans to extend Sullivan Street northward to Washington Square that prompted Harriet to sell No. 47 the following year. The project would require the demolition of the houses directly to the east and certainly upset the domestic tranquility within Harriet's home. The advertisement in the New York Herald on March 3, 1872, put a positive spin on the undertaking:

For Sale--The four story, basement house 47 South Washington square, facing the parade ground...the extension of Sullivan street will make this a corner house.

Eerily, the plaster walls of the interior rooms and even the ghost of the attic staircase of No. 49 remained following its demolition. photo by Brown Brothers, September 8, 1905, from the collection of the New York Public Library

It continued to be private house until 1886. Interestingly, while Washington Square North maintained its patrician personality, Washington Square South was seeing change (quite possibly a side-effect of the Sullivan Street extension). That year John Bernard leased No. 47 and hired builder J. J. Shannon to make modifications.

The alterations to the house proper were seemingly minor, costing the equivalent of just over $7,000 today. In the rear yard, however, he erected a two-story structure to house his "metal work shop," which employed 45 workers.

Bernard seems to have been experiencing business troubles a decade later. In April 1897 he cut his staff's salaries, prompting the men to walk out in protest. On May 10 the New York World reported, "While they were on strike they held meetings in the east side labor lyceum...where they listened to speeches by August Waldinger, of the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance." After two weeks of his shop being shut down, Bernard restored the men's wages. The New York World reported that his staff announced "that they had won their strike and would organize the whole trade."

In the meantime, the house was being operated as a boarding house. Among the residents by 1892 was the family of J. Ramar. He was the treasurer of the French Non-Sectarian Schools, a day-care school for preschoolers of working French immigrant parents. The group took no children over the age of six, "as we wish them to go to the public schools and to become good Americans," said its president Adolphe Cohn in The New York Times on January 10, 1894.

The Ramars' daughter, Bertha, had won the heart of a young German man, Paul Munsch by 1892. The 26-year-old was a designer of embroideries and lived in a boarding house on West Houston Street. It may be that it was an unrequited love, however.

On February 22, 1893 he came home "in a happy mood," according to his landlady, Mrs. Wendell. He did not have supper, but instead, "he seated himself opposite a picture of Bertha Ramer, who lives at 47 South Washington Square," according to The Sun, "and played the guitar. Then he wrote a poem to her, which he sealed up and went to his room."

Later as Mrs. Wendell passed his room she heard labored breathing and found him lying on the floor, dressed in his best suit, having shot himself. He was taken to St. Vincent's Hospital.

Suicide was a crime which could land Munsch in jail. From his hospital bed he claimed his pistol had gone off by accident "while he was examining it," as reported by The Sun. However, incriminating letters were found with instructions "as to what shall become of my debts, and I hope that you, my friends, will comply with my last wishes." He explained those away by saying he wrote them quickly after being wounded. Two sealed letters were addressed to his mother and to Bertha. "Perhaps they may explain the shooting," said The Sun.

Among the tenants in No. 47 in 1904 was sculptor William Whitney Manatt. Born in Granville, Ohio in 1875 he was by now well established within the New York artistic community. He received a commission to sculpt a bronze bust of William Jennings Bryan in 1904, but the orator and politician's busy schedule presented a problem.

On June 22, 1904 The New York Times explained, "Mr. Manatt began the bust some time ago, using a photograph as a model. Then he appealed to Mr. Bryan to grant him an hour's sitting for the finishing touches." Bryan complied and posed in Manatt's Washington Square South studio on June 21. "He said the likeness was excellent," said The New York Times.

William W. Manatt created this bust of Bryan, now in the Nebraska Hall of Fame, in his studio at 47 Washington Square South. photo by Capitolist

Another tenant that year was an enterprising businessman who called himself Father E. Monteleone. He marketed his "Iride Lotion" as curing "wrinkles, pimples, freckles, smallpox marks, each and all facial blemishes." A "special bottle for smallpox" cost $3.00--a significant $90 in today's money.

That William W. Manatt choose No. 47 for his studio was a reflection of Greenwich Village's--and Washington Square's specifically--becoming the center of Manhattan's art community. In 1914 sculptor Michael Brenner and painter Robert J. Coady opened the Washington Square Gallery in the ground floor of the house.

The gallery opened in December that year with an exhibition of works by Coady and Brenner, as well as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Diego Rivera, Henri Rousseau and others. It remained in the space until 1917 when it moved to Fifth Avenue and renamed the Coady Gallery.

The house continued to cater to artistic and colorful figures. Living here in 1920 was Mrs. Cecile Sartoris, the granddaughter of President Ulysses S. Grant. That December her son Herbert was home from school for the holidays and the two went out for an evening with friends on Saturday, December 18.

The New-York Tribune reported that while they were out, "burglars entered the place and it is said, took 8,000 French francs, jewelry worth several thousand dollars, gowns, Russian sables, valued at $4,000, and a fur coat costing $1,500." The French currency had been donated to the French Restoration Fund, of which Mrs. Sartoris was vice-president.

Living here at the same time was "Teddy" Gerard, a star of the Ziegfeld Follies. On July 6, 1921 she placed a panicked telephone call to the Mercer Street police station. The New York Evening Telegram said, "A frantic voice...asked that a policeman be sent to Washington square and Sullivan street to stop some 'trouble.'" Policeman Carey arrived, spent an hour in the apartment, and then reported "everything serene."

Teddy Gerard insisted that a $15,000 diamond ring was missing. She was sure she had lost it "somewhere between a well known Fifth avenue restaurant and the Washington square address," said the New York Evening Telegram.

One hour later Gerard called again. Her maid refused to let the responding detective into the apartment, saying only that Miss Gerard found her ring." The actress-singer-dancer refused to discuss the matter further.

A reporter from The Yonkers Herald interviewed Gerard in her apartment in May 1923 following her triumphant European tour. The journalist said, "she can show you...many books containing many eulogistic comments on her success in Paris and London." The article said "she danced her way to success on the Parisian stage." Now she was embarking on a new venture. "Returning to America, Teddie Gerard's entrance into the motion picture field was unannounced until recently, when Inspiration Pictures, Inc. made known the fact that she has been filmed in 'The Cave Girl.'"

Teddy Gerard would soon have to find a new apartment. On September 2 that year The New York Times reported that "alteration work, which will practically amount to an entire rebuilding, is now in progress on three old houses at 45, 46 and 47 Washington Square South...The old houses have been for years in a much neglected condition." Architect Morris Whinston's renovation--costing $1.5 million in today's money--would result in what The New York Times called "roomy studio apartments with an admirable outlook over the Square."

In 1947 New York University purchased the full blockfront and announced plans to demolish all the buildings. The three renovated Federal houses were still home to writers and artists. It sparked the formation of the Save Washington Square committee, prompting the New York Herald Tribune to warn the development would "ultimately destroy the architectural and cultural values of this celebrated district."

The university compromised by designing the block-engulfing Vanderbilt Hall (named for Arthur T. Vanderbilt, dean of the NYU School of Law) in the neo-Georgian style and limiting the height to four stories. The complex was completed in 1951.

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment