When the stoop was removed, the door was lowered, resulting in comical proportions and an absurd transom.

In the early 1870s, John Hampton, a dealer in grates, and his family lived at 110 East 61st Street, one of a row of identical Italianate-style homes erected in 1869. The three-story-and-basement house was faced in brownstone and was 18.6-feet-wide. While the upper floor windows wore prominent cornices, the openings of the parlor floor were distinguished with Renaissance inspired pediments.

In 1876, Julius and Ida Binge purchased 110 East 61st Street. Julius was a partner in the brokerage firm Binge & Curie, founded in 1868 with Charles Curie. The couple had a daughter, Lottie. The Daily Canadian would later say the family, "possessed wealth estimated at several million dollars." It was most likely the Binges who added an attic floor with two prominent dormers.

An expert on customs duties, Binge filed many claims for over-charges. The Daily Canadian said, "It is said that these over-charges on customs amounted to nearly $4,000,000, and that he received $1,000,000 for his service."

Julius Binge was focused on a more personal overcharge in 1878. He won a suit against the city that year, awarding him $10.40, the "amount of Croton water rent, for 1876, paid twice on premises No. 110 East 61st street."

Decades later, in 1907, readers of newspapers across the country would be riveted by the shocking arrest of Lottie, who was now married to Leopold Wallau. After Julius's death, Ida had moved into the Wallau house at 68 East 80th Street. On February 18, 1907, The Cairo Bulletin ran the headline, "Woman Held For Mother's Death," and reported that Lottie was charged with first-degree murder in Ida's sudden death. The Daily Canadian wrote, "Were Mrs. Binge's days of torturing invalidism shortened by poison administered by a sympathetic hand--an act of mercy that the patient daily begged from daughter, doctor and friend?"

Ida had suffered with "a cancerous growth [that] was literally eating through her whole system," said The Daily Canadian. Public sympathy, according to numerous newspapers, was on Lottie's side. And on March 19, 1907, a grand jury dismissed the charges. The Scranton Truth ran a headline, "Mrs. Wallau, Freed Of Charge Of Killing Her Mother."

In the meantime, Julius and Ida Binge had sold 110 East 61st Street to Moses and Amelia Ottinger in 1880. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency would recall decades later, Ottinger, "was born in Wittemberg [sic], Germany, immigrating to this country with the parents at the age of three." Amelia, said the article, was "a New York city girl who was in the first graduating class of Normal, now Hunter College." The couple had a son, Nathan, who entered New York City College in 1888.

Moses Ottinger and his brother Marx were real estate operators. Among the structures they would erect while Moses lived here were 20 Bridge Street and the Appleton Building at 72 Fifth Avenue.

The Ottingers remained here until April 1899, when they sold the house to M. H. Campbell, triggering several rapid turnovers. In 1902, Julia P. Jay purchased it for $45,000 (about $1.6 million in 2025), and sold it the following year to newlyweds Joseph Frailey Smith (known professionally as J. Frailey Smith) and his wife, the former Annie May Callaway. The couple were married on November 20, 1902.

Born in Philadelphia in 1871, J. Frailey Smith was an attorney, described by The New York Times as "a well-known clubman and a Director in several corporations." He was vice president of the Metallic Decorating Company, and a director in the Phenix Cap Company and the Phenix Cork Company.

On October 23, 1906, The New York Times reported that Smith was said, "late last night to be dying in Roosevelt Hospital of injuries received in a fight early last Wednesday morning at Forty-fifth Street and Broadway." The article said, "Every attempt was made to keep the facts from coming out, and the only details of the matter on the court records are contained in a short affidavit."

The attempt to keep the embarrassing details from the public was understandable. J. Frailey Smith had been with "a well-known actress playing in a Broadway Theatre," at Broadway and 45th Street around 3:00 a.m. Smith became involved with a "dispute" with three men that escalated into fisticuffs. Smith was knocked backward, fracturing his skull on the sidewalk.

Despite Smith's tenuous situation, he survived both his injuries and, apparently, the scandal of infidelity. Annie was pregnant at the time of the humiliating coverage. Five months later, on March 29, 1907, the couple had a son, Samuel Callaway.

Joseph Frailey Smith died on March 1, 1910 at the age of 38. Annie left 110 East 61st Street in October 1912, when she rented it to Edward M. McIlvaine.

The next year, on November 9, 1913, The New York Times reported, "Mr. and Mrs. Devereux Milburn will live at 110 East Sixty-first Street during the Winter season." A week before the article, on November 2, The Sun published a half-page spread about the society marriage of Devereux Milburn and Nancy Gordon Steele.

A graduate of Oxford University, Devereux Milburn was the son of millionaire John G. Milburn. An attorney, he was called by The Sun as, "the well known polo player." Indeed, Western New York Heritage would describe Milburn as being, "remembered as possibly the best polo player this country ever produced."

The Milburns in 1913, the year they rented 110 East 61st Street. from the collection of the Library of Congress.

Devereaux and Nancy Milburn left 110 East 61st Street in 1916. That October, Annie Smith leased the house to senior vice president of the Guaranty Trust Company, Grayson Mallet-Prevost Murphy. He was, as well, a director of the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, the New York Trust Company, and five other corporations.

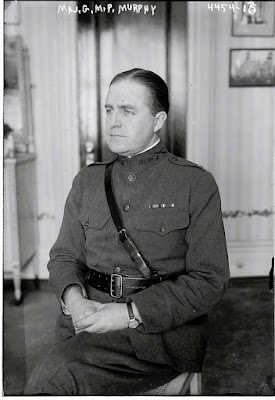

Born in 1878, Murphy graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1903 (after having already served as a volunteer in the Spanish-American War). During World War I, as a rank of lieutenant colonel, he organized the American Red Cross in Europe. While living here in 1918, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for "his foresight, wisdom, and untiring efforts" and "marked ability as assistant chief of staff of the 42d Division" during the war.

Grayson Mallet-Prevost Murphy was living at 110 East 61st Street in 1918, when this photograph was taken. from the collection of the Library of Congress.

On July 24, 1920, The New York Times reported that Annie May Smith had sold 110 East 61st Street. It was purchased by Frank T. Wall and his wife, the former Emily Unckles, who were married in 1905. Wall was the treasurer of the Wall Rope Works, Inc. The couple had one son, Fenwick W. Wall. (Frank had five children from a former marriage.) Wall was born in Williamsburgh, New York in 1856, the son of the first mayor of Williamsburgh. (Williamsburgh would later lose the "h" and be consolidated into Brooklyn.) The family's country home was in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Moving into the 61st Street house with the Wall family was Emily's widowed father, Thomas H. Unckles. He died here on January 20, 1922 at the age of 88 and his funeral was held in the parlor on January 22.

The Walls were in Greenwich on June 30, 1928 when Frank T. Wall died "after a prolonged illness," according to the Cordage Trade Journal. Unlike his father-in-law, his funeral was not held in the house, but at St. Bartholomew's Church.

Emily Wall sold 110 East 61st Street the following year. It began a chapter that would have shocked its previous socialite owners. The basement level was converted to what ostensibly was a restaurant, called Chez Richard. But court documents regarding a case tried in 1931 noted that the restaurant, "110 East 61st Street [was] of the kind known in those days as 'speakeasies.'" And Chez Richard is included in the long list of speakeasies documented in David Rosen's book, Prohibition New York City--Speakeasy Queen Texas Guinan, Blind Pigs, Drag Balls & More.

A renovation completed in 1937 resulted in furnished rooms throughout the house (the restaurant was now gone). In the process, the stoop was removed and the entrance lowered below grade.

In 1948, 29-year-old writer Paul de Man moved into a room here. Remembered today as a literary critic and literary theorist, he was struggling at the time. In his The Double Life of Paul de Man, Evelyn Barish writes,

Moving while skipping out on the rent became his best and probably his only budgeting technique. He located an apartment through an acquaintance at 110 East Sixty-first Street...The building was a classic brownstone, converted to walk-up apartments, where he stayed for a few months before moving to the low-rent Jane Street in Greenwich Village.

A second renovation, completed in 1955, resulted in two apartments per floor. A second entrance, slightly below the original, was now accessed by a metal staircase.

The building's most celebrated tenant came in 1956 when newly married Woody Allen and Harlene Susan Rosen moved in. The budding filmmaker and actor was 20 years old, his bride was 17. David Evanier, writes in Woody: The Biography, "They soon moved into a one-room apartment at 110 East Sixty-first Street." Like Paul de Man, their residency would be short. They moved to West 75th Street before long.

It appeared that the end of the line for 110 East 61st Street was near in the 1980s. The Ausnit family had amassed a large "inventory" of buildings along the block in the 1950s. Together, they seemed to be ripe for development. Instead, however, the family liquidated the properties, including 110 East 61st Street, in 1987.

There are still ten apartments in the building.

photographs by Ted Leather

many thanks to reader Ted Leather for suggesting this post.

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment