When developer William Manice hired Wallis & Goodwillie to design a 12-story "brick and stone store and loft" in 1911, he was perhaps taking a risk. While the firm was well-established, Architecture magazine commented on December 15, 1912, "The architects of this building were almost untried in work of the loft building type."

A respected architect, Frank E. Wallis also wrote articles and books on architecture, while his partner, Frank Goodwillie, specialized in the engineering aspects of their projects. Just before they received the commission for the Manice Building, Arthur Loomis Harmon left McKim, Mead & White to join Wallis & Goodwillie.

The plans, filed in July 1911, projected the construction cost at $350,000--about $11.6 million in 2025 terms. Completed the following year, any doubts about Wallis & Goodwillie's ability to design a loft building were quickly erased.

Architecture magazine began its critique on December 15, 1912 saying, "Considered from an architectural viewpoint, the Manice building, Wallis & Goodwillie architects, Arthur Loomis Harmon, associate, may be placed at the head of the loft building class. It demonstrates better than anything we can recall how excellent results are obtained by the introduction of a new thought on an old problem."

The tripartite Renaissance Revival design was defined with materials (stone at the base, sandy colored brick at the midsection, and white terra cotta at the top level) and prominent intermediate cornices. The limestone base featured a double-height arcade and an elaborate band of Renaissance inspired panels. Architecture commented, "The most beautiful features are the entrance doors, in delightful detail, and the ornamental band, carved in low relief, at the third story level."

Architecture, December 15, 1912 (copyright expired)

Above the relatively unadorned midsection, Wallis & Goodwillie created deep, double-height recesses, each supported by a single Corinthian column. "The cornice is of wide Italian or Spanish type," said Architecture, "executed in copper."

It was that cornice that impressed The American Architect, which commented that it, "represented the inspiration of the Lombard rather than the Tuscan architects; characterized by a greater beam thickness and wider spacing, they present a pleasing variation of the type."

The unusual treatment of the recessed upper windows separated by a column can be seen in this detail. The American Architect, January 27, 1915 (copyright expired)

The Manice Building filled with the workshops and showrooms of wholesale apparel firms. Among the earliest were J. & F Goldstone, Zaiss & Engel, Leon Jobin, George H. Montrose & Co., and Maurice Bandler. The latter, which fashioned women's coats, marketed itself as, "The House of Coat Cleverness." In its August 1912 issue, Crerand's Cloak Journal said, "The Manice Building is almost desirable as an American Rue de la Paix, for it is tenanted from top to bottom only by firms of the highest class of whose products this market is justly proud and whose producers are men competent to speak with authority on all matters pertaining to the world's fashion."

Visitors to the Manice Building stepped into a marble lined lobby with mosaic floors, bronze trim and elaborate coffered ceilings. Architecture & Building, December 15, 1912 (copyright expired)

Crerand's Cloak Journal said, "The Manice Building is a triumph of modern factory construction, for few would imagine from the palatial appearance of this magnificent and ornate office building situated in New York's most fashionable thoroughfare...that it was a busy hive of the garment industry where several thousand workers are gathered under one roof." While those garment workers labored at their sewing machines in the back areas, the elegant showrooms mimicked their counterparts in Paris. In August 1912, Crerand's Cloak Journal devoted an article to "the palatial show rooms."

In each French-inspired showroom, buyers inspect new garments on live models.

Buyers at the Maurice Bandler showroom (above) are separated by French panels. Below, a model exhibits a dress to a potential customer. images from Crerand's Cloak Journal, August 1912 (copyright expired)

Like the other tenants in the building who manufactured suits, dresses and other women's fashions, Maurice Bandler sent its designers to Europe every year to get inspiration (some might say steal) from the current trends. In a full-page advertisement in the Dry Goods Economist on July 18, 1914, Maurice Bandler assured buyers that its fall line would be on point with Parisian fashions. "We have had our designers make an exhaustive study of the style trends abroad...To buyers afflicted with doubt and worried by the uncertainty existing in many quarters, the Bandler line offers a haven of security."

Fashion houses continued to occupy the Manice Building. In 1916, Markowitz Co., Inc., makers of "high class dresses and costumes," as worded by The American Cloak and Suit Review, moved in, and the following year Goldberg-Goldschmidt Costume Co., Inc. signed a lease.

In the meantime, the 20,000-square-foot ground floor space was home to Amos T. Hill Furniture Co., Inc. The firm's high-end, handmade furniture was displayed in the Madison Avenue side, while its factory was entered at 157 East 32nd Street. An advertisement in Good Furniture in May 1917 said in part, "Exclusive and individual designs in furniture for the living room, dining room and bed room are on display in our show rooms." A photograph in 1918 shows large bronze lettering above the second floor: "Amos T. Hill Furniture."

The four brownstone residences demolished for the Manice Building were similar to those at the right. Architecture & Building, December 15, 1912 (copyright expired)

The Floersheimer Company, makers of dresses, moved into the Manice Building in December 1918. Albert Floersheimer ran a non-union operation, explaining to the New-York Tribune in February 1921 that, "he was paying his employees more than the union scale [and] that working conditions in his factory were of the best." Although his workers seemed to be content, the union was not.

Early in 1921, the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union began lobbying the Floersheimer workers to unionize. Albert Floersheimer filed suit on February 24, "for a permanent injunction to be issued" to the officers of the union. The affidavit asserted that the union's purpose was, "to increase the revenue of the international union, which thereby would get new members who would be required to pay $17.50 for a membership book."

Floersheimer emerged victorious over the powerful union. On March 24, 1921, the New-York Tribune reported that the injunction was granted, restraining the union "from picketing...and from trying to force their employees to join the union."

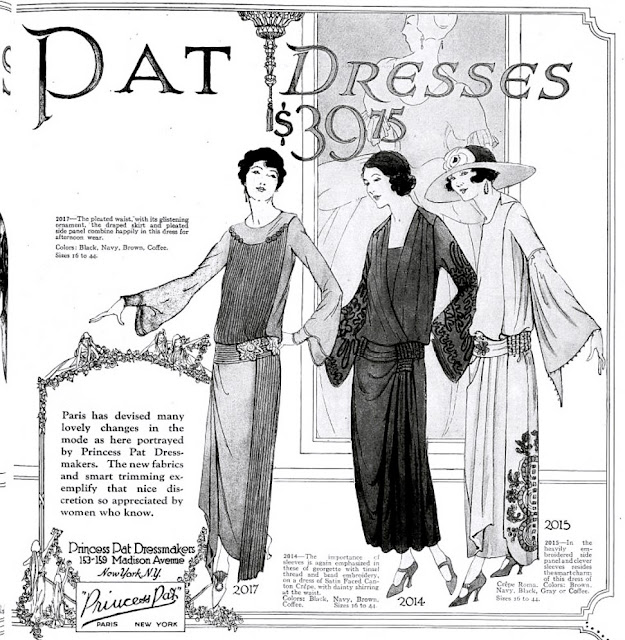

While apparel makers like Princess Pat Dressmakers still occupied the Manice Building in 1923, others were migrating into the newly developing Garment District above 34th Street. At the time, silk dealers were moving into the Madison Avenue district. On May 11, 1922, the New-York Tribune reported on the first of these, saying that R. & H. Simon, Inc. "one of the largest silk and ribbon manufacturers in this country," had signed a lease.

On November 22, 1924, the New York Evening Post noted, "Present indications seems to portend that the intersection of Madison avenue and Thirty-fourth street will be the future center of the silk trade." By the end of the decade, silk dealers Wullschleger & Co., Majestic Silk Mills, Theodore Fruchtman (who made men's silk ties) and Royal Textile Co. occupied the building.

Wullschleger & Co. was founded in 1908 by Swiss-born Arthur E. Wullschleger. In a 1925 brochure describing the firm's large silk weaving of The Signing of the Declaration of Independence, Arthur Wullschleger said, "the volume of business has reached a turnover of many millions of dollars annually, sales of over a million dollars having even been booked in a single month."

In 1925, large lettering on the cornice above the third floor reads "Wullschleger & Co." The Signing of the Declaration of Independence, 1925 (copyright expired)

As Adam T. Hill had done, Wullschleger & Co. prominently affixed its name to the Madison Avenue facade. It would be replaced before 1936, when the Bethlehem Furniture Company name was emblazoned above the second floor in bronze letters.

The Exquisite Form Brassiere Company purchased the building around 1950 and leased the ground floor to the Guaranty Trust Company. On June 12, 1960, The New York Times reported that the Exquisite Form, Inc. (it had dropped the Brassiere from its name by now) intended to move its operation to Pelham Manor, New York. The article said the firm had offered its tenants to buy the building, "who will jointly own the twelve-story structure in the same way that a cooperative apartment building is owned by its tenants."

Instead, in 1961, the General Electric Company leased the entire building for its international division. The New York Times reported on August 10, "Renovations have been made, including full air-conditioning, remodeling of the lobby and the installation of automatic elevators."

General Electric Company occupied the Manice Building through the early 1970s. Then, on October 17, 1976, The New York Times reported, "A 61-year-old [sic] office building in Murray Hill...is about to be recycled into a luxury apartment house." Joel I. Picket, president of the Gotham Construction Corporation, had purchased the building for $1.8 million. He announced that he and his partners would "turn the building into a 180-unit apartment house."

From the street, the striking Manice Building, described in 1912 as the head of its class, is nearly unchanged.

photographs by the author

.jpg)